Essay

Are We Really What We Read?

In her essay titled ‘The Critics, The Monsters And The Fantasists’, pre-eminent fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, ‘To throw a book out of serious consideration either because it was written for children, or because it is read by children, is in fact, a monstrous act of anti-intellectualism.’

Le Guin’s essay resonated with me as an adult because it put into words a sentiment that I carried as a child. The sentiment being a dislike of preconceptions when it came to intelligence and, by extension, one’s choice in literature. Just as writers of fantasy have had to defend their writing against the pedantic and literal eye of their critics, readers have had to contend with being considered ‘dull’ or ‘dumb’ because they chose to read books that were not considered suitable by the general population.

Given that these were labels that I was stuck with from an early age, I realised the role these preconceptions can play in shaping a person. And how they could have affected me had I not had guidance from the right quarters at exactly the right time.

Where It Went Wrong

The economic liberalisation of India, which began in the 1990s, brought with it the promise of rapid economic and social development.

Unfortunately, the same level of development was missing when it came to the quality of children’s literature that was available in my school. One section of my school library was filled with uncared for, palm-sized hardcover books whose bindings were disintegrating and the covers of which held one of two names: Enid Blyton (The Famous Five, Noddy) or Edward Stratemeyer (Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys).

The other section included classics like A Tale Of Two Cities, The Hound Of The Baskervilles, Oliver Twist, Moby Dick, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, A Christmas Carol, etc. Even the abridged versions of these classics gave students like me enough analytical nightmares to dread going to the library. Books of leisure, thus, became an eagerly sought-after retreat from the drudgery of schoolwork.

But the more I read what was offered in the school library, the more I came to loathe reading in general.

With the passage of time, and Indian adults being the way they are, I realised that not only my report card but also my reading choices (or lack thereof) were being used to pigeon-hole me into a category of intelligence. In other words, I wasn’t considered to have much of it since I hadn’t devoured all the Blytons and Stratemeyers, nor did I know my Ahab from my Ebenezer. This led to some rather short conversations with adults and classmates alike once they learnt about my reading habits, since a boy who didn’t read what everyone else did was clearly a boy whose intellect was questionable and one whose company needed to be avoided. Unfortunately, this was an issue that haunted me for most of my childhood.

Where It Went (Sort Of) Right

Thankfully, I was blessed with parents who were bibliophiles, and they never failed to indulge my reading habits, despite my colourful report card. Having already amassed an impressive home library, they introduced me to authors such as Clive Cussler, A.J. Quinnell, Tom Clancy, Robert Ludlum, Lawrence Sanders, and a host of others. All of them helped to nourish and nurture my imagination in a way that the prescribed literature of the day could not. My vocabulary and way of thinking advanced at a rate faster than that of my peers. And I suddenly found myself in the position of helping out some older students with basic grammar and comprehension.

This rapid development did come with its downsides. The preconceptions people had regarding my reading choices led me to be misunderstood at best, and dismissed at worst. As a result, I was forced to be at the receiving end of a blank stare from a disapproving teacher or an uninterested friend too many times to count.

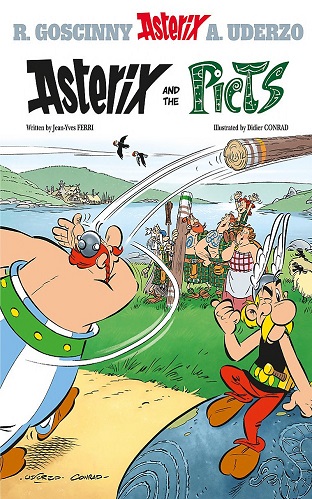

But the one place where I was always understood was at home by my parents who indulged my reading habits, and took the effort to understand just what I was reading and how I was comprehending it. Their ability to keep an open mind about all kinds of literature prevented the generation gap at home from turning into a chasm. My parents understood me through my choice of literature, and I them through the quality of their guidance. To this day, a new issue of Asterix or Tintin is as coveted by my parents as it is by me. And for that, I am blessed and thankful.

Even in school, while the likes of Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle would be lauded for their study of the human condition, authors like Oscar Wilde, Colette and Vladimir Nabokov were never discussed. The one time I asked our school librarian for a copy of Lolita, she gave me a stare on par with what Anubis gives the souls that are brought to him for judgement. In the end, I felt lucky to leave the library with my soul intact.

Where It All Came Together

Keeping my reading choices aside, my parents were always supportive of my inquisitiveness even when it came to topics like sex, homosexuality, abuse, drugs, alcoholism – topics that a lot of my peers couldn’t openly discuss at home with their parents. However, I must add that keeping an open mind and indulging a child’s inquisitiveness is one thing, but doing it responsibly is quite another. Indulging curiosity is by no means an excuse to expose ideas and concepts to minds that are not ready for it.

Here, too, my parents chose to guide me through the material that was appropriate. My experience of reading Mario Puzo’s The Godfather stands out as a great example here. Having already seen the film, I knew what to expect from the character of Sonny Corleone and his proclivity for extra-marital affairs. But when a particularly descriptive moment of physical intimacy came up, I did not hesitate to ask my parents about it. And they did not hesitate in telling me that while it was the act of sex being described, the manner of writing was not how I should perceive physical intimacy between two people. Though I had further questions, I was promised further instructions once I’d reached an appropriate age – a promise that they kept.

Responsible indulgence thus ensured that there were never any awkward moments between my parents and I while watching a film or enjoying a TV show. The shared moments were those of universal laughter and a feeling of friendship – one that I realised was missing for many children at the time.

I do believe that the difference between ‘censorship’ and ‘supervision’ is a desire to explain. Leaving children (or even adults, for that matter) to their own devices when it comes to understanding complex topics is as irresponsible as not introducing them to said topics to begin with. It was due to a supervised indulgence of my reading habits that I learnt that a differing opinion may weaken my argument but would, ultimately, strengthen my knowledge. I also learnt that it was possible to be well-read and still remain ignorant.

I was saved from going down the path of ignorance and distortion by my parents and certain teachers who were willing to indulge my inquisitiveness in literature and, by extension, an inquisitiveness about life.

Without the shackles of preconceptions, I was able to acquire a perspective on things that allowed me to not just understand life but also live it. The importance of academic training and its uses were not lost on me, and although it would have been beneficial, I was never pushed to pursue academics at the expense of my recreational reading and imagination.

In the pursuit of academic brilliance, the role of imagination is often overlooked. As Robin Williams said in Dead Poets Society – ‘We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is full of passion. Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.’

Literature is the tool that shapes our personalities and our imagination, and having preconceived notions about its suitability is like ignoring an oasis in the middle of a desert due to a preconceived certainty that it must be a mirage. It is forgivable to be blind to intelligence, but not to be intellectually blind.

Arjun hails from the city of Nagpur and comes from a long line of teachers and academicians. He holds a Post-Graduate Degree in International Business from San Francisco and has been writing poems and short-stories on/off since 2011. You can follow his Instagram page, where he reviews books and movies, here.

You can read his articles, here.

Well written and articulated views of an exceptionally unique youngster.

Carry on writing Arjun – you have a gift …. and you are blessed to have had parents who actively nurtured and encouraged your literary skills.

Thank you so much for the encouragement. And yes, I have been truly blessed to have had such parents.

Absoleutely fantastic….thanks♥️

No. Thank you:)

Very well written. Enjoyed reading your piece.

I’m glad you did sir.

Excellent writting..agree with your preconceived notion of literature..I am victim to it…hope to explore more openly…

Excellent writing ..agree with your preconceived notion in reading..I am victim to it..looking forward.to be more experimental.

And I’m sure that experiment will be successful.

Simply loved the essay Arjun. Currently mothering a 15 year old, your words resonate so much with what I’m experiencing. I sometimes felt that my teenager was reading way too much, and making less friends….an avid reader myself, I won’t deny I have tried to dictate or approve/disapprove her choice in reading. A difficult phase this is, like you said to let them venture out but also to be open about discussing so many things. I guess your essay is a ready reckoner for all. 🙂👍

I’m so glad that the essay resonated with you. A rather doting older-brother to a younger teenage sister myself, I sometimes despair at her choice of reading material and I sometimes feel like staging an intervention. However, I remind myself that it is her choice, and she should learn to work out for herself what is and isn’t pleasing to her palette. Your daughter is lucky to have a mother such as you, and you are equally fortunate in having a child who is receptive to the culture of reading. I wish both you and her all the very best on your respective reading journeys.

I simply loved the essay Sir. Being a teenager myself, I can relate with each and every word penned by you herein. True, we often overlook what we are actually reading for: a different realm of imagination and end up getting trapped within the literary boundaries

Thank you for appreciating my essay. I am glad that you could relate to it.

I think I have mentioned this before, but no harm in repeating….You are one helluva lucky boy to have such “suljhe hue” parents.

Great article Arjun and even better thought processes.

Thank you. Yes, I am indeed fortunate:)