Exploring Class And Gender In Soniah Kamal’s ‘Unmarriageable’

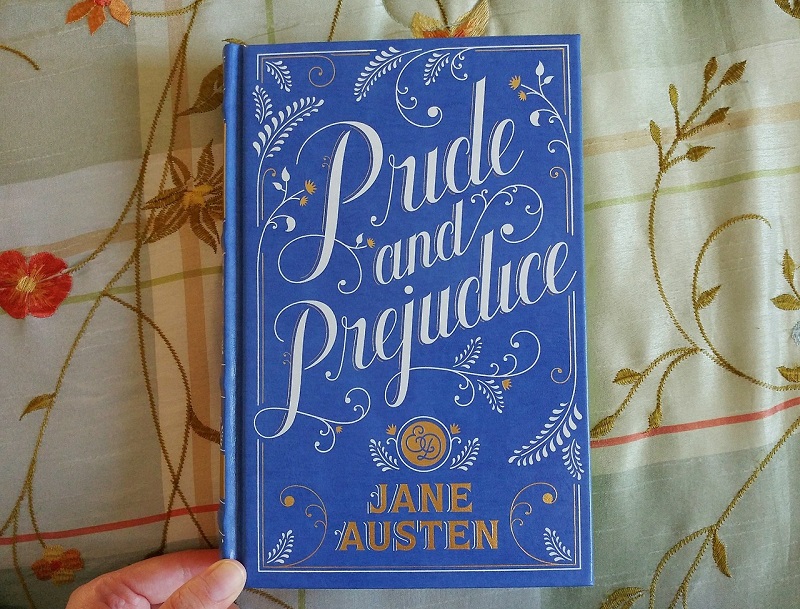

Thus begins Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice – a Regency-era novel that is a sharp and witty commentary on class, society, gender and marriage.

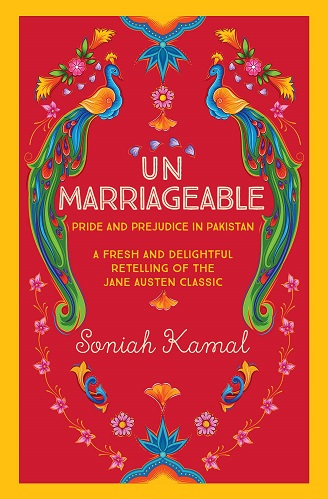

Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable: Pride And Prejudice In Pakistan is a fresh and delightful retelling of this classic novel. Set in the small town of Dilipabad, the novel traces the life of the Binat family as they traverse through marriage, gender and sexuality in a heavily norm-ridden upper class Pakistani society.

Kamal’s retelling focusses on the need for former colonies to be able to tell their own stories, even though a good part of the postcolonial imagination accessible to the West is coloured by an English language education. It is, therefore, part of a postcolonial writing tradition that plays with the English language, and reclaims it by peppering in local inflections, writes parodies, retellings, spin-offs and questions what it means to write in English.

Unmarriageable is an indication of how class structures and gender roles have remained the same over time and space. Kamal’s Pakistani upper-class society and its gender roles are like Austen’s, and yet she writes her characters in a manner that makes the reader aware of these parallels. Her novel, thus, becomes an interesting text through which one can explore the intersecting politics on class and gender in a postcolonial space.

The Marriage Conundrum

Similar to Regency-era England, Kamal’s book portrays marriage as mobility for women and is a topic that occupies much of the plot as well as the drawing room discussions between characters.

The novel begins with the protagonist Alys’ student announcing her engagement to a class of excited teenagers and progresses to the family attending a fancy high society wedding. The novel’s title also sets the tone for much of Alys’ criticism about the institution of marriage. The discourse around marriage in Unmarriageable provides an insight into the intricate politics of women that are tied to their class location and social status – a fertile site to introspect the multiple feminisms emerging in the novel’s narrative.

Alys disapproves of early age engagements, compares marriage to sex work, rejects two proposals over the course of the novel, and is often rebuked for being vocal about her disdain for the institution of marriage. Her ideas about marriage are deemed ‘too progressive and radical’ by her family and friends, especially when juxtaposed against the obsession with marriage shown by the women around her.

However, an important caveat to her character is her idea of agency that is influenced by Western liberal feminist traditions, an indication of her privilege. Therefore, much of Alys’ criticism towards marriage is actually a criticism of the tradition of arranged marriages – a phenomenon common in South Asian societies. She sees the concept as propagating class endogamy – as the wedding ceremony of the Dilipabad elites indicates, leaving women with little opportunities to express their needs, marred by the remains of the dowry tradition and the financial burden it brings upon the women’s families. She is also critical of how marriage dominates the imagination of most families with daughters, as with her own mother, making it a pre-empted reality that is almost impossible to escape.

The opportunity of choosing one’s life partner and marrying for love remains an appealing idea for Alys, who is otherwise the least romantic of her sisters. This, perhaps, is tied to her relentless desire to be able to make her own decisions. Interestingly, although she does pick her own partner, he belongs to the same class as her and shares much of her privilege, thereby provoking the reader to wonder if the result of Alys’ agency differs from the arranged marriage she constantly resists.

Privilege And Politics

Kamal spins this narrative around marriage on its head when Sherry, Alys’ best friend and confidante, accepts the proposal of the very rich and respectable but utterly boring Dr. Khaleen. Sherry belongs to a humble background and has several barriers that affect her ‘choice’.

Unlike Alys’ international school education in Jeddah and links to one of Pakistan’s prosperous feudal families, Sherry is, in her words, ‘Dilipabad-born and bred’. She teaches Urdu to high school girls, and is unmarried in her early 40s. For her, a ‘good marriage’ is an escape from her family that considers her a burden and from her suffocating life in Dilipabad where she is seen as an oddity. For Sherry, an arranged marriage becomes an emancipatory possibility rather than the stifling institution imagined by Alys.

When Alys confronts Sherry about her decision to marry Dr. Khaleen, she calls out Alys’ privilege that gives mileage to her brand of politics. She reminds Alys of her family name that allows her to make social connections that would otherwise not be possible. Sherry tells Alys that marrying for love has never been an option for her since her reality is very different from the bubble of privilege Alys continues to bury herself in.

This is a pivotal moment in the novel, especially when the reader takes into account the politics of Pride And Prejudice. Suddenly, the question is not about whether the canonical text is a piece of feminist literature, but whether it is a deeper introspection into who that brand of feminist politics favours. The feisty feminist protagonist of the original novel acquires new dimensions when in the postcolony, thus starting a conversation on feminism in South Asia.

(Image via Siddy Says)

Postcolonial English And Its Politics

Class formations in former colonies do not usually follow the trajectory of other industrialised Western countries – like Austen’s England. Among its many distinguishing markers is the access to the English language. This retelling, therefore, is also a reminder that despite claims of decolonising the language, English continues to primarily remain accessible to the upper classes in the postcolony. It is confined to families of feudal and royal origins, trapped in fancy boutique cafes, gymkhanas, snazzy parties, posh schools and other elite settings. It continues to evade the access of many, and its usage remains aspirational.

These linguistic politics, enmeshed with its class implications, are embedded in the narrative of Kamal’s novel. Alys’ mother, Mrs. Binat, is a caricature aunty-stereotype obsessed with finding good matches for her daughters and is a source of comic relief due to her mispronunciations, her Urdu-fied English and her desire to appear posh. This realisation is important since it makes the reader aware of the intricate and gendered family dynamics of the Binats.

Mrs Binat is constantly rebuked and ignored till the end of the novel when Alys realises that the turbulent dynamic between her parents emerges from her mother’s lower-middle class family background and her own contribution towards her mother’s marginalisation. Alys’ ‘progressive’ ideas are so deeply-rooted in her international school education, her job, her social status that she conveniently forgets that her mother did not have access to the same.

Kamal is, therefore, self-aware in her portrayal of Mrs. Binat – her access to high society comes through a good marriage, her lack of a college education is mocked by her family and also determines the power relations within the household, giving her daughter and her husband the leeway to never take her seriously. Much of her desire to speak good English (and her relentless attempts at it) stem from her desire to fit into a family that has unlimited access to the language and therefore, to a culture that the language encapsulates within it – English literature, American movies, the ability to seamlessly ‘belong’ in social gatherings.

Through Mrs. Binat, Kamal explores the idea of access to English in the postcolony, the privileges and affiliations that come attached with the language itself and its inseparability from one’s status. Kamal’s Unmarriageable, therefore, does what Austen’s Pride And Prejudice intends to do – it uses wit and humour to mirror the society we inhabit and comment on its absurdities, making the reader acutely aware of the parallels with their own lives.

(Image via A Kernel Of Nonsense)

The parallels with the original thus remind us that despite all our progress, very little has truly changed over time.

Sounds like *Unmarriagable* does engage with Pride & Prejudice’s idea that marriage is an economic proposition. In P&P, Elizabeth is shocked that her friend Charlotte marries the foolish Mr. Collins, b/c Collins is silly. Liz disapproves of marriage as an economic proposition. Charlotte tells Liz that she’s fine with marrying for financial comfort. Liz herself turns down Darcy b/c she doesn’t like him — but when she visits Darcy’s estate, she feels ruefully that she could’ve been mistress of all this…

The Liz-Charlotte debate precludes any generalised answers to the question, “Is it wrong to marry for money?” One sympathises with Liz as the sensible, independent protagonist — but the reality is that her father has not much money, and five daughters with no profession open to them. Had Liz not fallen in love with Darcy, and had he not proposed again — one wonders what compromise she’d have made to fend for herself. Marry someone like Mr. Collins? Become a governess?

I like that *Unmarriageable* engages with the economic questions around marriage. The fact is that even today marriage remains an economic proposition for many women — and that it’s affluent women who can afford not to face this fact.