The Femoir: The New Face Of Feminist Storytelling

Deya Bhattacharya

August 31, 2018

Femoirs or female memoirs are becoming an imperative literary tool as women’s engagement with writing is intensified. But what are femoirs, and how did they come to be? What spurred women to use memoirs as a medium to put forth their lived realities? Do femoirs actually amplify the voices of all women? Has the rise of femoirs caused any limitations on or obstacles to women’s writing?

The word ‘femoir’ came to be used in August 2012 by Kaitlin Fontana in her piece The Rise of the Femoir, where she charted the growth of a new literary genre – “memoirs written by female comedians”. At that time, as Fontana coined this term, a string of confessional essays by female comedians came to be bestsellers – Tina Fey’s Bossypants, Sarah Silverman’s The Bedwetter, Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? – yet, Fontana’s term came to be seen as a niche. Through Fontana’s piece, it is clear that the femoir became an excellent marketing tool for female comedians. The comedic memoir, Fontana states, is a “career requirement for any funny person”; it was, in many ways, a long-form version of a standup set that supports the establishment of a comedian’s voice for a more substantial audience. But she also pointed out how it seemed to be a requirement only for female comedians – “You can be a male comedian and not write a memoir. But if you are a female comedian, you would be stupid not to.”

However, since Fontana’s article in 2012, the definition of femoirs seems to have undergone a transformation. It is no longer only a mouth-piece for the female comedian where the author share anecdotes about her life, in an attempt to indicate that she is inspirational but not infallible. The femoir, as a representation of female comedians, also had its limitations – the authors had to be in the public eye, but they were also required to speak to all women. The female comedian’s femoir used feminism as a tool, rather than making a substantive feminist statement.

For example, in her memoir Sick, Porochista Khakpour chronicles her tryst with Lyme’s disease. She recounts her experiences as a person who was constantly ill, and how countless doctors misdiagnosed her with depression, anxiety, diabetes, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue, as they were reluctant to take her symptoms seriously. Sick is not a convenient medical memoir where Khakpour’s narrative shifts from impeccable health to illness – it is a feminist telling of a woman’s lived realities with debilitating physical pain and anguish. Khakpour brings out the uncertainty and confusion as a patient whose symptoms are disbelieved, and how as a woman and a person of colour, she is tempted to invisibilise her own narrative of symptoms, when the medical community misdiagnoses her.

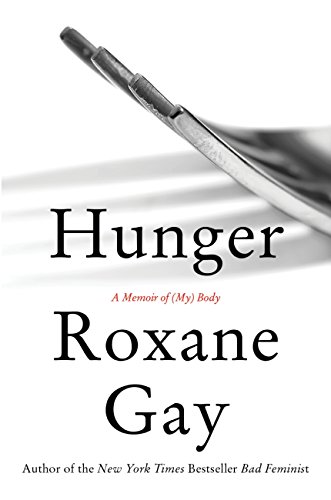

In Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, the author explores her journey of living in a body that the world feels entitled to judge. In her unapologetic telling of how she came to be morbidly obese, she confronts the trauma that provoked her struggle with food and her body: she was gang-raped when she was 12, in an isolated cabin, by her boyfriend and his friends. In this femoir, Gay, who is a feminist and a fiction writer, explains how food was the only cure to the torment of being raped and keeping it a secret from parents and loved ones for years. Her telling of her own story is structured in a before and after manner, where her memories are stained with shame and shock and appear scattered. The reader is continuously faced with Gay’s desire to become healthy and thin, and at the same time, feel comforted by the “fortress” of her fat. The book is disturbing, in ways that only the truth can be, as she is forced to navigate and negotiate a world that feels compelled to punish and censure the unruliness of her body.

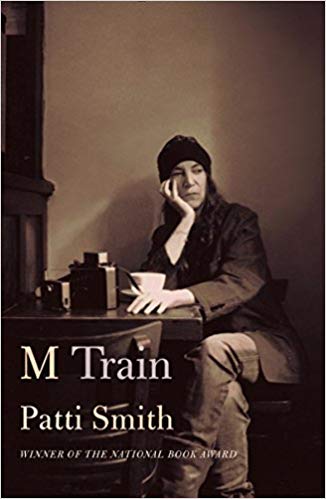

Patti Smith’s M-Train gives us a glimpse of Smith’s solitary soul through her travels which mirror her trains of thought. In the book, we discover Smith is enamoured by her trips to London, Mexico City, Tokyo and Berlin where she pilgrimages to the homes and graves of her beloved writers – Frida Kahlo, Jean Genet and Sylvia Plath. And yet, her mornings at a café near her New York apartment are her most cherished. Smith spends her days writing or daydreaming at Café ‘Ino, where she has brown bread, olive oil and copious amounts of coffee. In the book, Smith is a lone woman committed to her art and the reader feels this power as she tears through her daily solitary routine.

Femoirs are important in the present day and age, as there is truth in how women are portrayed. There are no flourishing and inauthentic shows of strength, but there is power in the prose of femoirs – a power that speaks of a journey where women have spent years under nom de plumes and male disguises to seem relevant to their audience, a power that is testament to the ways in which women’s lived realities challenged archaic literary canons to construct a new one.

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.

Great piece! Are there any Indian femoirs? Do any of Twinkle Khanna’s books count?

I haven’t read Twinkle Khanna’s books. But looking at the blurbs, I would argue no. Her books try and give us a picture of the world around us, but her narrative is not feminist. I would not denigrate their content and call them “chick-lit”, but I would not consider them femoirs either.

Does that make sense?

Yes, thanks!