Go-To Book

To Improve Your Grammar, Read Dreyer’s English

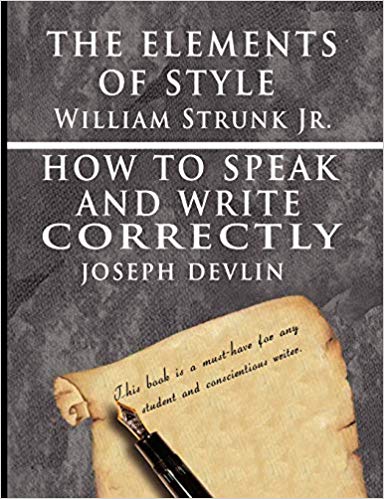

There is a myriad of books that seek to teach aspiring writers how to become better at their craft. There are books on how to write better dialogue, how to plot and how to develop characters. And then, there are books that help writers write well and not make the kind of grammar faux-pas that give editors a headache. For years, The Elements Of Style by William Strunk Jr. was the go-to book for anyone who wanted to learn how to use correct grammar and punctuation. However, it is not without its critics. In The New York Times, five experts opined on whether the rules in The Elements Of Style are the “be all and end all of writing?” and all five found the book to now be largely irrelevant and even, at times, wrong.

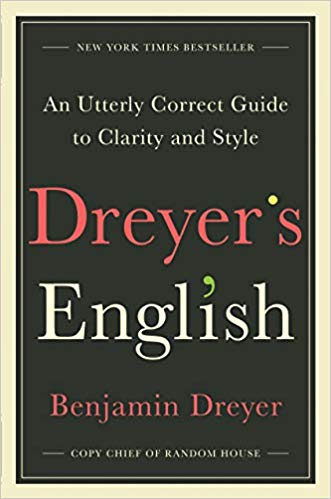

And this is where Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide To Clarity And Style comes in. What makes this book special is that it isn’t prescriptive. Dreyer doesn’t tell you what to do so much as he explains why you should use a particular grammar rule and teaches you tips-and-tricks to work around them. This handy manual is not only perfect for anyone who wants to become a better writer, but also for those who love the language.

“This book is about writing, born of my nearly thirty years working in publishing as a proofreader, copy editor, and copy chief.”

You may be wondering who Dreyer is and why you should care about what he has to say about grammar. He is the copy chief and executive managing editor at Random House U.S. and has worked with authors like Michael Chabon, Peter Straub, E.L. Doctorow and Elizabeth Strout. Trust me, he knows what he’s talking about. Dreyer’s English is funny, witty and teeming with anecdotes, excerpts, and examples- all of which make it a must-read for anyone who is even remotely interested in writing well.

“It’s a book about writing, and clarity (and how to achieve that), and style (and how to at least aspire to that), all in the service of that single language we, at heart, share.”

Dreyer’s English was published in early 2019 in the U.S. and was completely rewritten for a U.K. audience. As he notes in “Englishes: A New Introduction”, there may be trivial differences between U.S. and U.K. English, in terms of spelling and punctuation, but these differences matter. He serves up an anecdote of how he once spent an hour asking his U.K. friends what a “decent replacement word” for squash (the kind you drink) would be. He ended up going with Coca-Cola because he just couldn’t come up with an alternative which would make sense to an American reader but would not be “inauthentic to a UK narrator”. He highlights that there are many dialects of English and has even included a note on Indian English.

Despite being written primarily for a U.K. audience, this book is relevant to an Indian audience as well because, technically, we follow the British English system. We follow similar grammatical and punctuation rules, apparently. Interestingly, as you read this book, you’ll realise that we use a mix of both American and British English. A favourite example of mine is that British English doesn’t add a full stop after Dr, but we do and so do the Americans.

“Here’s your first challenge:

Go a week without writing

• very

• rather

• really

• quite

• in fact”

He goes on to suggest also removing the words ‘just’, ‘so’, ‘pretty’, ‘of course’, ‘surely’, ‘that said’ and ‘actually’ from your vocabulary. According to Dreyer, avoiding the use of these words for just a week will automatically make you a better writer.

If you take a gander at it, you’ll find it quite difficult to actually follow his advice. That said, I can’t, however, deny the value of it. These words have become an very integral part of our vocabulary and it will take a conscious effort to do away with them while writing. Take a look at this paragraph and note how much better the prose is without the words that have been struck through. So, as Dreyer suggests, feel free to write them but then go back and get rid of each and every one of them. “And if you feel that what’s left is somehow missing something, figure out a better, stronger, more effective way to make your point.”

Pro tip: Scour the Internet for lists that can make it easier for you to find replacements for many of the words on Dreyer’s list. In office, we have a list of words on our corkboard that can be referenced to get rid of ‘very’. For example, very noisy becomes deafening, very poor becomes destitute and very scared becomes petrified.

“The English language, though, is not so easily ruled and regulated. It developed without codification, sucking up new constructions and vocabulary every time some foreigner set foot on the British Isle… and continues to evolve anarchically.”

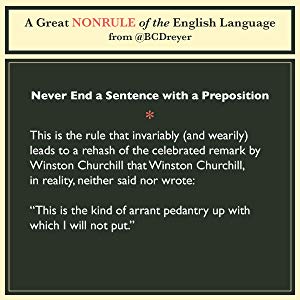

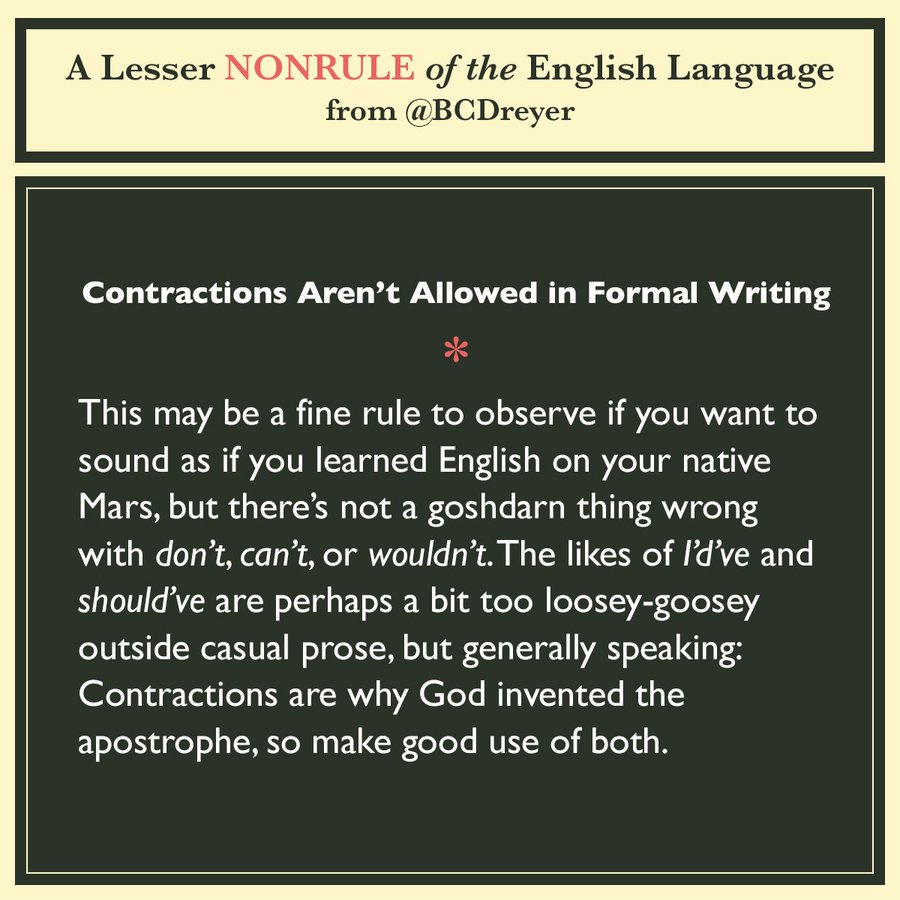

While Dreyer believes that certain rules should be followed, he is also a “subscriber to the notion of ‘rules are meant to be broken’ – once you’ve learned them.” To this end, he discusses what he refers to as the Great Non-Rules of the English Language. These are rules we’ve been taught but serve no real purpose. The three main Non-Rules are ‘Never Begin a Sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’ (with the caveat that you shouldn’t make a habit of it); ‘Never Split an Infinitive’; and ‘Never End a Sentence with a Preposition’. Perhaps, the most interesting non-rule though is to avoid passive voice. Dreyer doesn’t see anything wrong with sentences written in the passive but does suggest that “a sentence can be improved by putting its true protagonist at the beginning”.

“If words are the flesh, muscle, and bone of prose, punctuation is the breath. In support of the words you’ve carefully selected, punctuation is your best means of conveying to the reader how you mean your writing to be read, how you mean for it to sound.”

This isn’t news to us. Punctuation is important and a misplaced comma can change the meaning of a sentence. Dreyer runs through 66 of the most interesting “punctuational issues” he has come across. They range from why it’s important to use a series/Oxford comma to comma splices, from how to use apostrophes correctly to the dreaded semi-colon. As you read the rules, you’ll wonder whether or not you truly learned grammar in school and are likely to wince at all the ridiculous mistakes you’ve made over the years. Read the book to find out whether it’s ‘farmer’s market’ or ‘farmers’ market’ or ‘farmers market’? Hint: One is wrong and two are right, in different contexts.

Never before have punctuation rules been explained in such an interesting manner. Dreyer’s comments on the use of italics, and specifically, that we should make sure we don’t overuse them, is great advice for anyone who writes online. You’ll learn how to correctly punctuate parentheses, colons, hyphens, and question marks, and to avoid the use of double exclamation points because “no one over the age of ten who is not actively engaged in the writing of a comic book should end any sentence with a double exclamation point or double question mark.”

“I don’t hate grammar. I hate grammar jargon.”

Dreyer admits that he is not familiar with grammar jargon and has, therefore, made a conscious effort to make his section on grammar simple. On page 94, I learned about the pernickety danglers. His meditation on ‘not only x but y’ constructions made me realise that I’d been using them incorrectly all my life. His reflection on the use of ‘they’ as a singular pronoun is like a mini-essay on the evolution of the usage of ‘they’ along with suggestions on how to avoid using it. And yes, he does discuss how to use ‘who’ and ‘whom’.

“Spellcheck is a marvellous invention, but it can’t stop you from using the wrong word when the wrong words you’ve used is a word (but the wrong word).”

Keeping this mind, the second part of Dreyer’s English is dedicated to helping you choose the correct word. Dreyer takes us through a list of words that are often confused with each other (lay/lie, anyone?) and those that are frequently or easily misspelled (minuscule, publicly). You’d be wise to bookmark the chapter on ‘trimmables’ because I can guarantee you’ve been making many of the mistakes he writes about. Do these sound familiar- added bonus, absolutely certain, close proximity, general consensus? Yes, they are all redundancies. As is fiction novel. And my pet peeve- free gift. Then there is ‘unsolved mystery’, which is also wrong because “once it’s solved, it’s not a mystery any more, is it.”

“This book, then, is the next conversation. It’s my chance to share with you, for your own use, some of what I do, from the nuts-and-bolts stuff that even skilled writers tumble over to some of the fancy little tricks I’ve come across or devised that can make even skilled writing better.”

This really is what the book is about- the basics that many of us have not revisited since our childhood. The Internet hasn’t helped as grammar, spelling and punctuation rules are easily suspended in favour of our need to write in 280 characters or less. Over time, many of us have made it a habit to flout these rules and soon, we’ll find ourselves stuck with a language we no longer recognise or love. Dreyer’s English reminds us that English can be fun and that learning grammar doesn’t have to be tedious, or for that matter, difficult. All you have to do is bookmark (or dog-ear) or stick Post-its on to the sections of this book, which you are likely to reference repeatedly, and keep it next to you, at all times.

Devanshi has been reading ever since she can remember. What started off as an obsession with Enid Blyton, slowly morphed into a love for mystery and fantasy. Even her choice of career as a lawyer was heavily influenced by the works of Erle Stanley Gardner and John Grisham. After quitting law, and while backpacking around India, she read books on entrepreneurship, taught herself web design and delved into social media marketing. She doesn’t go anywhere without a book.

She is the founding editor of The Curious Reader. Read her articles here.