Feature

The Politics Of Immigrant Families In Fiction

Hamsini Ravi

September 27, 2019

Family life is one of humanity’s most universal experiences, across class, geography, race, religion and time. Though acquired naturally at birth for the most part, relationships between parents and children and among siblings can be tenuous and a struggle for the best of us. This is particularly true in the context of immigrant families, when the children are flitting in and out of worlds that are at once alien and frustrating to them, trying to meet multiple expectations while carving out a niche identity for themselves.

In the past few decades, writers like Jhumpa Lahiri and Chitra Banerji Divakaruni have made fictional writing about immigrants a genre by itself, by constantly making their protagonists pine for an elusive home, painting scenes of casual racism and dialogue exchanges that smack of internalised reverse culture shock. I love the struggles and joys that come with being an immigrant. Chimamanda Adichie is another writer who captures the everyday dilemmas of an immigrant spectacularly and vividly. More recently, I read Min Lin Jee’s 2007 novel Free Food For Millionaires, a telling tale about a young woman’s post-college life that offers a look at the Korean American immigrant experience.

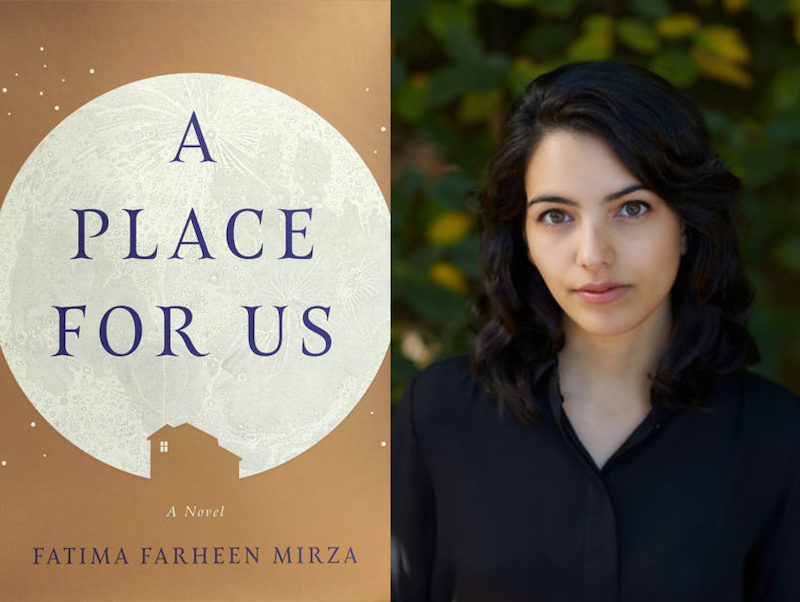

I picked up A Place For Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza, just after last year’s Eid. It blew my mind with its incredible commitment to tell a realistic story of an American-Indian Muslim family living in Northern California. A skilfully illustrated family saga that takes on a unique narrative, by moving between time and space, the book explores parent-child conflict, religious leanings and the immigrant desperation to succeed on the parents’ part versus a child, who has his own mind and desires to exercise it.

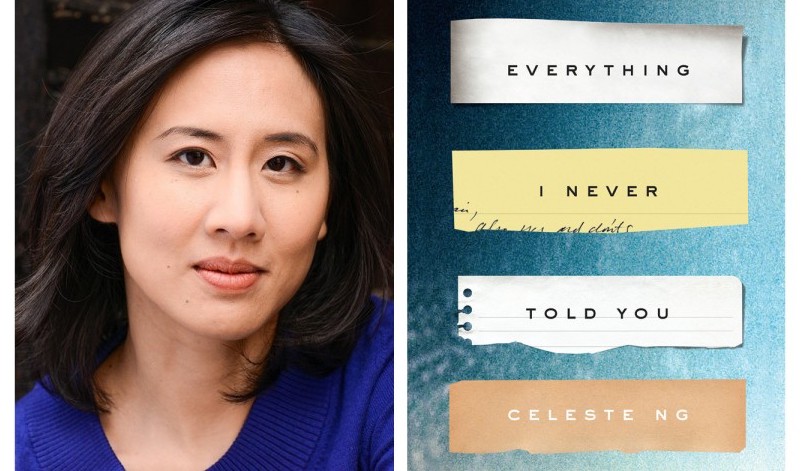

A few months after reading A Place For Us, a friend insisted I read Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng, a book published in 2014 that met instant acclaim and popularity. The book is a thriller of sorts and explores the circumstances of the death of Lydia, a high schooler in Ohio. Set in the 1960s, it delves into the story of each member of a mixed-race family, gracefully asking questions about race, gender, familial and marital love and identity in the context of a death of a family member. I was thrilled that the book pleasantly reminded me of A Place For Us. Though the books are set several decades apart, racism and religion as themes loom large in each of the settings.

Whereas A Place For Us is more of an exploration of the tension between individualism and community, through the lives of a family that is attempting to root itself in a foreign land as immigrants , Ng’s Everything I Never Told You essentially deals with the aftermath of an untimely death of the family’s eldest child, but has a plot that is much larger than the actual tragedy. The similarity with A Place For Us starts with the expectation dissonance between each parent and the child – in this case, each parent imposes their own failed ambitions on Lydia. Marilyn, the mother, wants Lydia to study medicine, something that she could not thanks to sudden familial responsibilities, whereas the father, James, wants to see her as a socially acceptable American teen, a stature he could never achieve, as the son of fresh-off-the-boat immigrants.

Mirza’s writing in A Place For Us sparkles as she gracefully illuminates family and community shia rituals while holding the big picture close and never letting the protagonists’ religious identity and ethnicity take too much away from the larger story. The characters are Muslim but are much more than that. The author consciously strives to achieve this by normalising and de-politicising their lives by vividly showing us activities they engage in, that are unrelated to their faith – the mother’s interest in gardening, the rebel son’s protest campaign for new shoes, the family’s ice cream store visits – these are all aspects that helped us look at the family as any other.

This decision to engage with the characters as people first and Muslims next seems to be a conscious choice on the part of the author who says in this interview, “To be honest, anti-Muslim or racist encounters are much more present than the book portrays — it’s like a constant low hum that is unnoticeable on most days, but will rise in volume when another brings attention to it……But for this family, I didn’t want to dwell in those encounters — I didn’t ignore them — but I felt very stubborn about wanting to guard them from being primarily accessed through that lens. The anti-Muslim interactions, the racism, the political context they live in — it puts an inescapable pressure on their lives, but it is also what others bring to them, the labels the world forces them to face. And I wanted to be with my characters when they were alone……. These are the very moments that fill their days, give meaning to their life, and the focus of their heart and attention, after all.”

(Image via Read It Forward)

In contrast, in Everything I Never Told You, the author says she drew a lot on her own racial experiences as an Asian American. Ng is drawn towards telling the tale of the outsider and has spoken about her own growing-up years in the U.S., where race was either black or white. “I always felt like a third party because I wasn’t either… I think Asians are in this weird space where they’re often lumped in with white groups.” Like Mirza, Ng has used plenty of scenes of microaggression to effectively portray racial experiences in the book. She says while she and the people she knows personally have experienced stronger discriminations, these experiences have been fewer as compared to those of everyday casual racism with people asking how they don’t have accents or how their English is so good or demand to know where they ‘really’ come from.

It is a testament to an author’s skill and unwavering consistency to be able to tell a tale that spans two decades in such a manner that the reader starts connecting with each of the characters’ thoughts and desires, even pre-empting what they would do next, in some cases. Both Mirza and Ng achieve this in their books. Mirza shows an outstanding understanding of human character and love. She says, “Sometimes, when following Layla’s or Rafiq’s (the parents) perspective, I was aware that I personally disagreed with their logic in the moment. Those were difficult moments to navigate but maybe the most important ones for me to sit with, as I had to articulate their experience as they would, and in doing so I had to imagine a thought process that was so unlike my own.”

The last chapter of the book is told from Rafiq’s point of view, during the evening of his life and evokes a sense of empathy towards the man’s sensibilities and the fact that like every parent, his actions were performed in the hope that his children would have the best of everything.

I found it interesting that Ng balanced the outlooks of the parents in her book with her own experience as a new parent. She says here, that before writing the novel, she wholly empathised with Lydia, but she gradually became more sympathetic to the parents after having her son. She says her own experience drove her to lend more nuance and perspective to the book – “I started to understand how deeply parents want the best for their children and how that desire can sometimes blind you to what actually is best.”

(Image via Los Angeles Times)

More than anything else, such examples of literary fiction consciously work on expanding the definition of an American family, to one that includes a multiplicity of racial, social, and economic experiences, while staying true to common afflictions that universally affect families – poor communication, expectation dissonance and a failure to truly understand what your child wants for herself.

In the face of a xenophobic political environment, literature like this that accommodates a variety of experiences is what the world desperately needs – to empathise, to listen, and to share and realise that underneath our skin tones and our ethnic clothing, we are all flawed beings desperate to be understood by our own kin.

As a child, Hamsini Ravi, would read books all day and well into the night even after her parents switched off her lights in her bedroom, she also used to read as she walked on the road to visit her grandparents, who lived a few doors away. Both have prepared her to read on the Mumbai locals everyday, as an adult.

Read her articles here.