A Renaissance Of Storytelling

Arjun Baburajan

February 22, 2018

“It’s like everyone tells a story about themselves inside their own head. Always. All the time. That story makes you what you are. We build ourselves out of that story.”

– Patrick Rothfuss

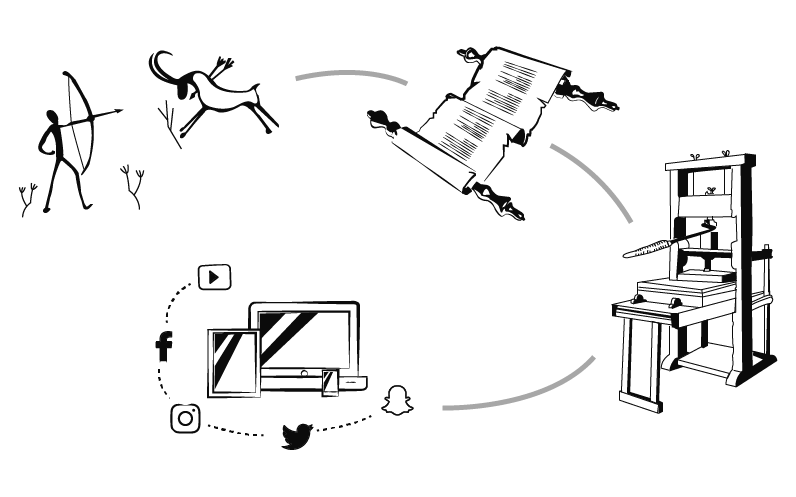

From the primitive art found painted on caves across the world to the forgotten libraries of Alexandria to the internet as we know it now, humanity has always had an ardent need to express ourselves and the world around us. Stories have been found carved, painted, written, printed or inked onto all kinds of media including wood, ivory and other bones, clay tablets, skins (parchment), paper, textiles, recorded on film and even stored electronically in digital form.

To understand this rapid progression in storytelling as seen in the 21st Century one must look to the past. Before Gutenberg changed the world with his printing press, storytelling, or any form of media for that matter, was restricted to a certain sect of people, whose sole job was to maintain records, known as scribes. Some of the earliest known scribes date back to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and documented at the order of their rulers. With the rise of the printing press, more ideas and stories were allowed to come into circulation. Although the ability to bulk print ideas brought about change, a lot of the stories printed were opposed by the “powers that be”.

For example, Galileo Galilei, the famous astronomer, and scientist who championed Copernicus’ theory of heliocentricism (the concept of planets revolving around the sun) with his own publications and his own astronomical discoveries went against the Church’s belief of geocentricism (the Earth being the centre of the universe). Despite the Church’s opposition, his contributions to the sciences lived on through the surviving copies of his publications.

What we should realise is that with the internet, there was no longer a need for a middleman between a person and his stories reaching the public. In fact, it has been replaced by an unbiased platform with the only restriction being one’s access to it. It encapsulates the culmination of the print and audio-visual media that developed in the previous century. Now, the internet’s manifestation of storytelling is seen in none other than the social media that is so very much a part of our lives. Stories of all sorts are shared and talked about, ranging from the smallest, seemingly most insignificant things like the lunch we had and our pets’ quirky little antics, to the most historical and important events such as the Arab Spring in the early 2010s and the recent 2016 United States elections.

The lack of a gatekeeper has led to a proliferation of new authors who have welcomed the opportunity to publish their work and find their own audience. Rupi Kaur is the poster child of this since her Insta-poetry has taken the world by storm and her books, milk and honey and the sun and her flowers have sold millions of copies. Her work has spoken to millions of young women around the world who have identified with the themes in her poems as well as the accessible nature of her poetry.

In India, Amish Tripathi sparked renewed interest in Indian mythology by self-publishing The Immortals of Meluha after it was rejected by several publishers. Using his management skills, he unleashed the power of the internet in marketing his book, such as making the first chapter available as a digital download and creating a live-action trailer film which he posted on YouTube. He also used social media to create a buzz around the trailer. The rest, as they say, is history.

We use stories to reflect upon our surroundings and the reality we live in. The narratives we choose are the ones which represent our perception of the situation. As are the books we choose as evidenced by the increase in sale of dystopian literature. In January 2017, Kellyanne Conway, counsellor to Trump referred to claims made by Sean Spicer, White House press secretary as “alternative facts”. While Chuck Todd rightly called them falsehoods, many were reminded of George Orwell’s 1984 where Big Brother constantly revised history to control the narrative. For 1984, Orwell developed a whole new language ‘Newspeak’ which was designed to purposefully omit certain words from vocabulary and introduce new ones because controlling language is the first step to controlling people.

If there’s one thing we know after having spent almost two decades in this new age, it is that stories can shift the course of history, regardless of their accuracy. Case in point: The radical use of false news reports and propaganda have now led us into the Trump era, where the truth is just a different point of view or to quote 1984, where “two plus two makes five”. Perhaps, Winston, the protagonist of 1984 got it right when he said, “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four.”

Dear Appu,

Keep on writing ?

I loved the last few paragraphs ???