Feature

The Tragic History Of Winnie The Pooh

Deya Bhattacharya

January 18, 2019

Can the intention of an author’s work be traced through their stories? Is it possible to saunter through their works and understand their primary motivations to create? Why did an author use a particular phraseology? Why did they reach out to a certain audience? What prompted them to tell the story in a particular way? These are often the questions we are confronted with when trying to piece together narratives about authors, their storytelling and their body of work. The connection between an author and their raison d’être to create is a sacrosanct space that sometimes readers are either unwilling or uninterested to explore. But it is an important space that contextualises their craft and provides for a structure for their impetuses to create.

I can trace the role of A.A. Milne’s Winnie The Pooh books in my childhood, like one would trace the map of Hundred Acre Wood to find ‘Pooh’s Trap for Heffalumps’ or the ‘Where the Woozle Wasn’t’ or ‘Eeyore’s Gloomy Place: Rather Boggy and Sad’. Pooh and his friends, along with Christopher Robin – the master of the animals – became a significant part of my growing up years. I grew up devouring the Pooh stories, sometimes reading with my grandmother, and at other times, alone – transporting myself to A.A. Milne’s perfectly created world for children. As a child, I viewed Milne’s work as isolated from himself – it seemed as if he had built a world and anthropomorphised characters for the enjoyment of little children. When I grew up, however, I began to view Milne’s motivations differently; there was more to his work than meets the eye.

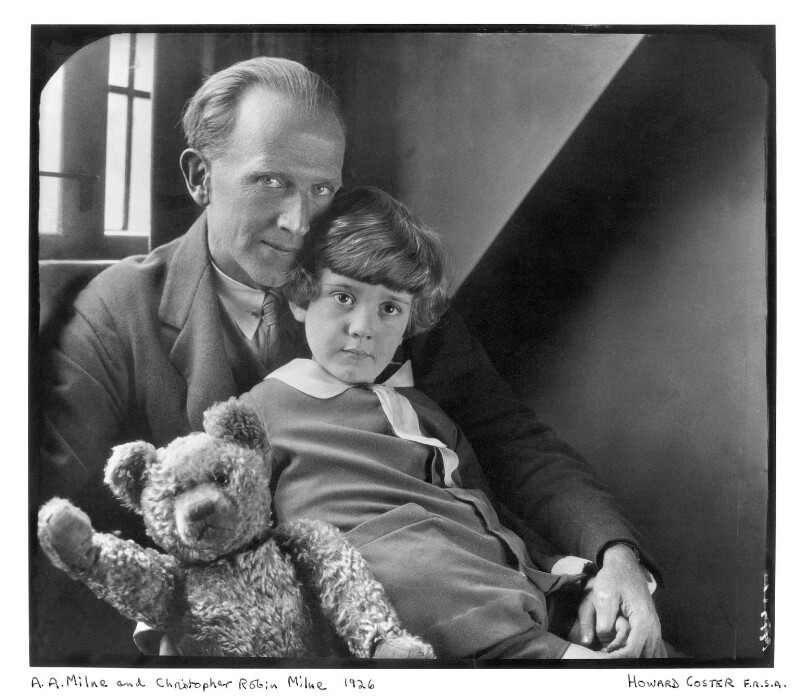

Milne’s Pooh books are about a boy named Christopher Robin, named after his own son, Christopher Robin Milne, and the other characters were inspired by his son’s stuffed animals – Winnie (previously Edward), Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo and Tigger – and Owl and Rabbit, that were created through Milne’s own imagination. Milne divided his work into four volumes known collectively as the Winnie The Pooh books – the first and third are books of verse while the remaining two are stories about Pooh Bear and his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood. For several years, after the publication of the series, the books of verse containing a few poems mentioning Pooh, were more popular than the stories.

In 1926, before Milne authored the Pooh books, he wrote, almost as if it was a prophesy, “I suppose that every one of us hopes secretly for immortality.” And he did achieve immortality, but perhaps not for the reasons that he intended. Milne’s life was inextricably linked with his work on Winnie the Pooh. The peculiar successes that the Pooh stories brought to him also took away from the reception that he expected from his non-juvenile writing. Despite his resounding accomplishments as a children’s author, his other work, such as editing the satirical magazine Punch, and writing a string of acclaimed plays, novels and short stories, all meant for adults, had been “irrevocably damaged”.

In the introduction to his play The Ivory Door (1928), Milne wrote, as if exasperated by his own successes, “It seems to me now that if I write anything less realistic, less straightforward than ‘The cat sat on the mat’, I am ‘indulging in a whimsy’. Indeed, if I did say that the cat sat on the mat (as well it might), I should be accused of being whimsical about cats; not a real cat, but just a little make-believe pussy, such as the author of Winnie-the-Pooh invents so charmingly for our delectation.” In his memoir, It’s Too Late Now(1939), Milne writes how he felt trapped by the image that the literary world had built of him being a children’s writer, “I wanted to escape from [children’s books] as I had once wanted to escape from Punch; as I have always wanted to escape. In vain. England expects the writer, like the cobbler, to stick to his last.”

(Piglet, Tigger, Winnie The Pooh, Eeyore and Kanga. The original Winnie The Pooh stuffed animals via New York Public Library)

Milne came to develop the Pooh books, because of his traumatic relationship with World War I. Because of his role in the War, he had been far removed from his family, and although there is no direct evidence of Milne’s tryst with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in his memoir, Milne writes that he was “almost physically sick” when he thought of “that nightmare of mental and moral degradation, the war”. The Pooh books were, in a way, an escape from the ravages of his experiences, and also a way to connect to his son, Christopher Robin. Milne’s anthropomorphisation of Christopher Robin’s toys changed the way he viewed his relationship to his son – he created a world for his son, with his son, in a way to get away from his own world. His world-building within the Pooh books gives a lot away about his own need to condense his grown-up, sagacious world inside his son’s: his books are set in the Ashdown forest, near which he lived. The make-believe world of Hundred Acre Wood was, in fact, Five Hundred Acre Wood, within Ashdown forest; Galleon’s Leap was inspired by a famous hilltop, Gill’s Lap.

This bridge that Milne creates between his world and his son’s is key to understanding his fragility, and therefore, the motivations behind his work. His books are suffused with a sense of happiness, albeit short-lived. This happiness is apparent in Pooh’s carefree antics within the book and in the shimmer and tremble of the Hundred Acre Wood. But this fragility also shows in the way that Milne portrays the character of Christopher Robin – the character is one that is all-present, and yet absent from the larger narratives of the Pooh books – “On the one hand he is Robin Hood revelling in the freedom of the Greenwood but he’s also a babe lost in the wood.” Milne creates this character in his own image; it is like Milne is watching in on Pooh and his friends, from the outside, through Christopher Robin. The character is often absent from any adventure; his primary role is to come in and make things right. In a blithe, adventurous forest, Christopher Robin moves with a sense of responsibility.

(A.A. Milne; Christopher Robin Milne and Pooh Bear by Howard Coster. Image via National Portrait Gallery)

How did his father’s loose grasp on reality impact the real Christopher Robin? Christopher Robin, who died on April 20, 1996, at the age of 75, was bullied in boarding school because of this fictional character. In The Enchanted Places, Christopher Robin Milne writes, “At home, I still liked [Christopher Robin], indeed felt at times quite proud that I shared his name and was able to bask in some of his glory. At school, however, I began to dislike him and I found myself disliking him more and more the older I got. Was my father aware of this? I don’t know.”

Christopher Robin grappled with Pooh’s successes and fame, as did his father, but his family did not protect him from the fame and publicity. He was given fan letters that people wrote to him, and he even wrote down responses to them diligently. He appeared in photographs with his father, and sometimes alone. At seven, he was involved in the audio recordings of his father’s books. At some point, Christopher Robin Milne also performed before 350 guests at a party, reciting his father’s books and poetry. Christopher Robin became the face of the books his father had created, and during his very childhood, the Pooh books had swallowed him whole. An article from Town and Country captioned a photograph of A. A. Milne as “English playwright. Children’s poet laureate by divine right of whimsy. His plays have been successfully produced in New York. And he is the father of Christopher Robin.” The tragedy of Milne’s Pooh books is that it trapped his son – “a real child in that moment like a fly in amber and made it almost impossible for him to become that thing that every child wants to become – a grownup.” What Winnie The Pooh did was that it cost the sanity of both Milnes – for A. A. Milne, Pooh meant that no one would ever take his literary work seriously, and for Christopher Robin, Pooh meant that he would forever be a child.

So, dear Reader, what were Milne’s motivations for writing the Pooh books? Was he trying to escape the ravages of war or did he intend to exploit his son’s childhood for his successes? Milne’s memoir chronicles his battles of being undermined as a literary writer after the publication of the Pooh books, as well as how miserable his life became after the war, but does not mention the negative impact that the books had on his son, who later became estranged from his father. A.A. Milne, through the books, had tried to capture his son’s childhood antics, and it was his audience who idolised Christopher Robin to the point of exploitation – they viewed Billy Moon (as Christopher Robin was called at home) as a prop for his books, and did not treat him like a real person.

Winnie The Pooh books are wildly famous, but as a reader, one must ask whether A.A. Milne wanted it to be so. The books took over the life of the Milnes, and in many ways, the creation swallowed the creators.

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.