An Introduction To Greek Theatre

Nirbhay Kanoria

March 27, 2018

For the Greeks, The City Dionysia festival was one of the most anticipated festivals of the year. It was a source of entertainment, a way to ‘revise’ their mythology, a chance to purge their souls, and not to mention, the social event of the year.

“World Theatre Day marks the occasion when the astonishing marriage of the singular and the plural, the objective and the subjective, the conscious and the unconscious will show the world the extraordinary creatures it has produced. Many of the discords in the world result from the estrangement of minds by the barrier of language: it is these discords and this barrier, which the huge and intricate mechanism of the theatre has set itself to overcome. Nations, thanks to these World Theatre Days, will at last become aware of each other’s treasures, and will work together in the high enterprise of peace.”

Cocteau is deeply influenced, like many others before and after him, by Greek theatre. It is no wonder that it has had such a deep lasting impact on theatre, as it is believed that it was at the City Dionysia festival that theatre itself was born.

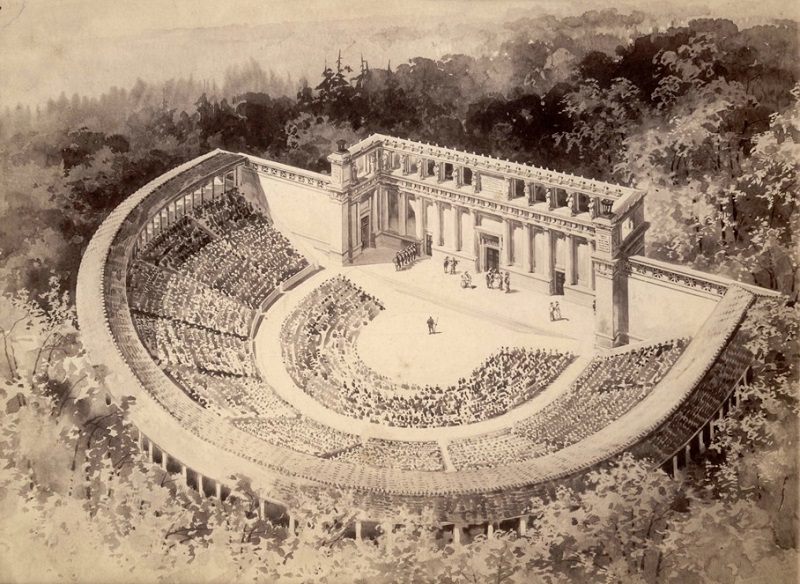

(The Hearst Greek Theatre by John Galen Howard via Wikimedia)

The Physical Theatre

Theatre comes from the Greek word theasthai which means behold, or more colloquially – to view. Theatron or Ancient Greek theatres consisted of three sections- the stage, the orchestra, and the audience. The audience sat in a semi-circular formation around the stage while viewing the play. Imagine you are in any modern-day theatre or opera– is the structure not almost exactly the same- the stage, an orchestra section and the audience seated semi-circularly in the stalls, balcony, and boxes? Furthermore, have you ever wondered why theatres have sloped seating? The simple answer is that it makes for easy viewing, but back in ancient Greece where there were no microphones and sound systems, a sloped seating allowed for an unencumbered passage of sound so the people seated at the back could hear the actors clearly.

(Ancient Theatre via Pxhere)

Brutality in Greek Theatre

Greek theatre is beautiful and, at the same time, gruesome. The stories are complex but the message is simple- sin and you will be punished. An unwritten rule in Greek theatre was that no brutality or gore would be shown on stage. All the bloody punishments would happen backstage and the chorus would convey the brutality through words and songs. So, when King Pentheus is ripped apart, limb to limb by his mother and her followers in The Bacchae, the audience never sees it. They are told of it in the following lines:

“You who dwell in this fair-towered city of the Theban land, come to see this prey which we the daughters of Kadmos hunted down, […] not with thonged Thessalian javelins, or with nets, but with the fingers of our white arms. And then should huntsmen boast and use in vain the work of spear-makers? But we caught and […] tore apart the limbs of this beast with our very own hands.”

(Orpheus and the Bacchantes by Gregorio Lazzarini via Wikimedia)

The Financer and Producer

Like many things theatre-related, the Greeks invented the concept of a producer. Back in ancient times, a good sponsor or chorēgos could make or break the play. Authors vied for the best chorēgos who would spend the most on their plays. The chorēgos was effectively a modern-day producer and financer, both rolled into one. He was a respected Athenian citizen who would be responsible for paying for the training of the chorus, arranging their costumes, and getting the backdrops and sets erected, amongst many other things. If his play were to win, he would often host a grand feast for the entire cast and playwright. Interestingly, it wasn’t just the love for the theatre that made a chorēgos choose to finance it, what often was a very expensive proposition. If his play won, his name would be inscribed on a monument which would be good advertising for him. Furthermore, if he were ever to end up in legal trouble, he could remind the jury of his contribution to society, and thereby get away with a leaner sentence.

(Choregos and actors via Wikimedia)

Catharsis

While it is nearly impossible to encompass all that is catharsis in a single paragraph, there are a few basics you should know. Aristotle first spoke about catharsis in his seminal work on Greek tragedy, Poetics. Catharsis effectively means a purification or a purging of one’s soul, and that is done through viewing a character go through his own emotional journey. The character realises his damnation has been brought about because of his own actions. To elaborate, in Oedipus Rex, the protagonist, Oedipus, has killed his father and married his mother, thereby fulfilling a prophecy given at his birth. While he did so unknowingly, the Gods are still punishing him for his untoward acts. When the audience finds out about Oedipus’s punishment, they feel the same intensity of emotions he is feeling and once the punishment is over, and he has paid the price of his sins, the audience feels purged and cleansed, as Oedipus would have after his punishment.

(Oedipe s’exilant à Thèbes by Hillemacher via Wikimedia)

We’re now back in 5th Century Athens, Greece. The performances have lasted nearly 10 hours. As is custom, a panel of 10 citizens has been chosen to decide the winner. They place their votes and a majority vote determines who wins. The winning play’s name is announced. The playwright, and his chorēgos, are both awarded. And just like that, the festival concludes. The audience is purged and spiritually cleansed with the multiple opportunities for catharsis that the plays have provided them with. They go home happy- feeling clean and whole again.

As a young boy, Nirbhay had the annoying habit of waking up at 5 a.m. Since television was a big no-no, he had no choice but to read to entertain himself and that is how his love affair with books began. A true-blue Piscean, books paved the path to his fantasy worlds- worlds he’d often rather stay in. Nirbhay is the co-founder and publisher of The Curious Reader.

You can read his articles, here.