Feature

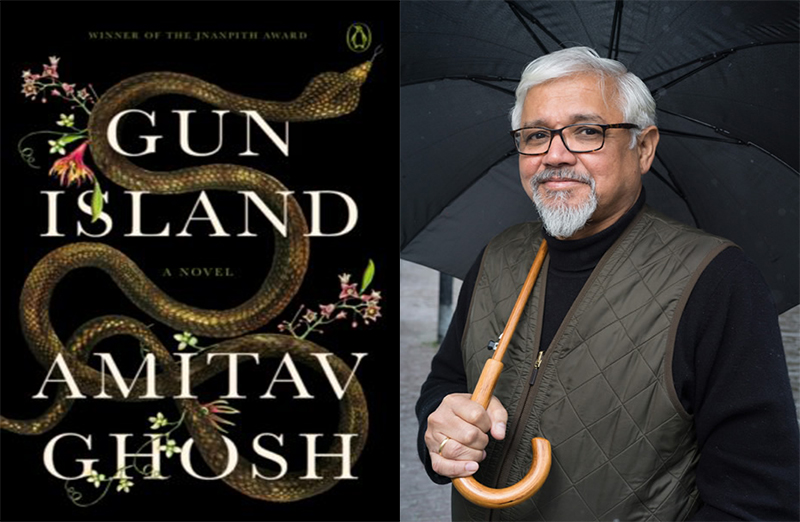

Exploring The Complexities of Immigration Through Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island

Amitav Ghosh’s fiction is beautiful, evocative, dreamy and lyrical, but it rarely addresses a pressing issue. Ghosh changed that with his recently released Gun Island, a sequel-of-sorts to his famous The Hungry Tide. He tackles two of the most relevant topics today in one fell swoop – climate change and immigration. The story follows Dinanath, a Bengali antique dealer who has immigrated to New York, as he explores the Sunderbans, Los Angeles and Venice, all the while encountering inexplicable phenomena that are a result of creatures being displaced from their native lands. When you read the novel you will be amazed at how this displacement is beautifully juxtaposed against the displacement immigrants feel when they leave their homeland and immigrate to foreign lands.

Why We Need To Think About Immigration

Look at the state of the world we currently live in. While India is happy to help Myanmar in building homes for the Rohingyas, it doesn’t want to accept them as refugees; the hottest topic of debate in the U.S.A. is whether or not immigrants are ruining the so-called American culture; and Brexit, honestly, was just a result of xenophobia. At such a time, when you read evocative fiction about immigration, such as Gun Island, the wheels of your mind start churning and you start to wonder what is it that immigrants go through. The book helps you see why someone is willing to leave behind everything they know and move to a foreign shore, where, in all likelihood, it will be hard for them to adjust and be accepted. It shows you how their fear for their lives or the inability to earn a living in their home countries precipitates the decision to immigrate.

In Gun Island, Dinanath, and his friend, Cinta, come across a young Bangladeshi immigrant while in Venice. Dino (as Cinta calls Dinanath lovingly) asks the immigrant what brought him to Venice in Bangla. Have a look at the exchange-

‘He’s from Madaripur, in Bangladesh, my own ancestral district. He left when he was eighteen and went to work in Libya. After two years he crossed the sea on a runner raft and ended up in Sicily.’

‘He came in a gommone?’ gasped Cinta. ‘But didn’t he fear for his life? Ask him- wasn’t he afraid to take such risks?’

I put the question to him and then translated his answer. ‘He says he never thought about it like that. He was in a group and they crossed over together, giving hope and courage to each other.’

Poignant and thought-provoking, right? Imagine how desperate one must have to be in order to willingly put their very lives at risk just so they can get to some place better, some place safer. And yet, when these immigrants land up on our shores, often we make them feel unwelcome.

Trump, Putin and Conte are just some of the more prominent world leaders who have famously argued against accepting immigrants because they feel the immigrants ruin the culture and economy of their countries. At a time when globalisation is unavoidable and there is only a lot to gain from learning about and accepting other cultures into your own, closing off borders is a sure-fire way to make sure your country suffers in the long run.

The world, as we know it today, has been built on the back of a constant flow of people moving from one nation to another. In the earlier passage, you saw a well-educated book dealer coming across a labourer, yet there was a connection because of their shared heritage. Most of us have descended from immigrants – all our families have moved for some reason or the other. Due to this, it is possible we will see a connection with a seemingly random person when we look beyond what’s on their surface. It may be as evident as the one Dino and the labourer shared, or it may be something more obscure, but this itself will create empathy.

(Image via Inc.)

What Do Immigrants Bring To A Country

Let’s spend some time pondering over whether immigrants ruin or add to a country’s culture and economy. Look at India, immigrants have always added to the melting pot that is this country. Babur fled current-day Afghanistan and made India his home and brought with him his traditions, music and art, which assimilated themselves into India’s culture, thereby creating a new and uniquely beautiful culture. The Parsi community emigrated from present-day Iran to India in the eighth century and has created a strong legacy in every field- be it politics, business, the arts or social service. Clearly, instead of diluting ‘true Indianness’, they have only added to our culture and economy.

In Gun Island, Ghosh makes a strong economic and social argument for immigration. Here’s what one of his immigrant characters says-

‘(Tourists) think they’ve travelled to the heart of Italy, to a place where they’ll experience Italian history and eat authentic Italian food. Do they know that all of this is made possible by people like me? That it is we who are cooking their food and washing their plates and making their beds? Do they understand that no Italian wants to do that kind of work any more? That it’s we who are fuelling this fantasy even as it consumes us?’

Immigrants don’t do only the low-paying and undesirable jobs; they’re also scientists, engineers, and business leaders. What many Indians called the brain-drain of the 1970s and ’80s, was when well-educated Indian men (and a few women) moved to other countries to start working in high-paying jobs. Did the economy of the countries they emigrated to suffer? No. In fact, in The Other One Percent: Indians In America, the authors argue that while Indians constitute only approximately 1% of the U.S.A.’s population, nearly 8% of the founders of high-tech companies are Indian, and they have greatly helped the economy.

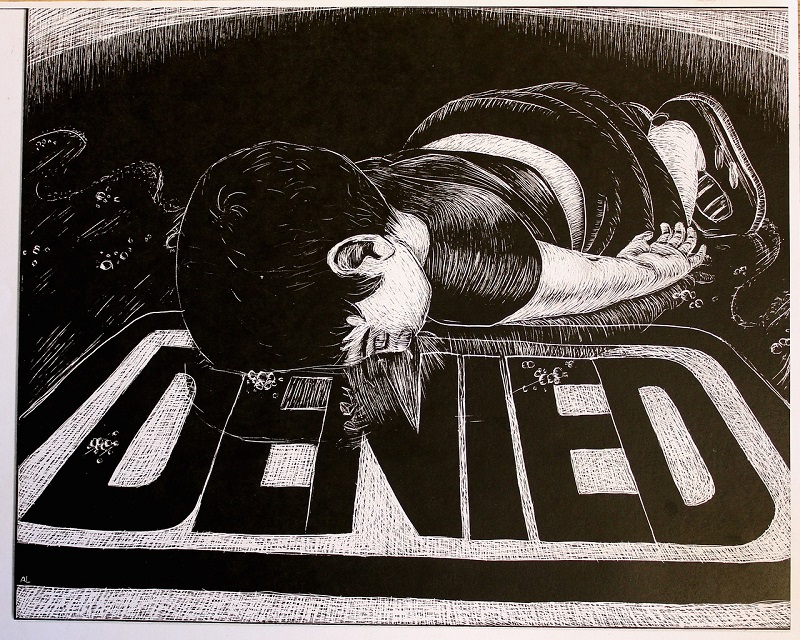

(Image via Dhaka Tribune)

How Immigrants Threaten Privilege

It is curious why young men and women from more developed nations are against letting immigrants in. What can ‘lowly’ immigrants do to such powerful and privileged folk? Ghosh sums it up as follows when he describes the angst of young Italians when they are protesting against a boat, which is carrying a group of would-be immigrants, from reaching their shores.

‘This is why those angry young men were so afraid of that little blue fishing boat; through the prism of this vessel they could glimpse into the unravelling of a centuries-old project that had conferred vast privilege on them in relation to the rest of the world. In their hearts they knew that their privileges could no longer be assured by the people and institutions they had once trusted to provide for them.’

And this is probably the crux of Gun Island – many who are from a privileged background (in the book’s case – white Christian men in Italy) tend to take their privilege for granted, and it becomes their way of life. Doors open more easily for them, they put in less work than others (females, minorities, etc.) and they tend to get the best salaries and jobs. And when immigrants come, it upsets the balance and status quo. The privileged lot, used to getting what they want, irrespective of whether they have worked towards it or not, are now being asked to work hard, and compete against those from poorer nations. Instead of ‘upping’ their skills and being more industrious, it is far easier to protest against immigrants.

The hostility that the natives feel against immigrants is evident in Gun Island when a young Italian threatens Dinanath with death, simply because he thinks he is a Bangladeshi labourer, or when right-wing activists take out a boat of their own to meet and potentially attack the boat carrying the immigrants out at high-sea.

(Image via Needpix)

Anti-Immigration Is Equal To Xenophobia

At the end of it all, we as a society have an issue with immigration because of xenophobia. Many Indians look down on Africans, call them druggies and think that they are ruining our culture. Actually, we’re scared of them because they look different from us.

Take India’s stand against the Rohingyas. While initially we were accepting of them, once Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia refused to accept them, we too turned our backs on them, leaving many of them stranded on the high seas or in ‘no-man’s land’ (i.e. the land between Bangladesh and India). Furthermore, some political leaders have even suggested deporting the Rohingyas whom we had already accepted. Worse still, hate-crimes against the Rohingyas, perpetuated by the ‘common-folk’ are also not unheard of.

We are scared of change, we are scared of what immigrants bring, we are scared of upsetting a status quo we have grown comfortable with. Before I read Gun Island, I had vague thoughts about immigration. While, in theory, I knew that I was all for it, I didn’t necessarily spend much time dwelling on it or thinking of what our nation’s stand should be, and certainly almost never on what immigrants go through when they do immigrate. This book made me want to explore the topic further, and while I understand that the topic is incredibly nuanced, it did make me far more empathetic to an immigrant’s plight.

As a young boy, Nirbhay had the annoying habit of waking up at 5 a.m. Since television was a big no-no, he had no choice but to read to entertain himself and that is how his love affair with books began. A true-blue Piscean, books paved the path to his fantasy worlds- worlds he’d often rather stay in. Nirbhay is the co-founder and publisher of The Curious Reader.

You can read his articles, here.

Wow, that is an interesting analysis. Ghosh has always been vocal about immigration and national identity through his other novels. I haven’t read Gun Island but now I will. You have made me curious with your line of thinking! Thanks Nirbhay.

Happy to know that! You should definitely read it!