Essay

How Reading Into The Setting Enhances A Book

Roald Dahl’s Charlie And The Chocolate Factory was the first novel that I finished reading at the age of 10. I remember posing many questions to my aunt, a teacher, such as, ‘what did the factory look like?’ and ‘how tiny are the Oompa-Loompas?’ She would answer by drawing parallels – the Oompa-Loompas, she told me, were small but human-like, a concept explained through illustrations from Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs. The only difference, according to her, was that they were somewhat magical. She also made me draw the factory to life while showing me a few pictures for reference. I created a blueprint of Willy Wonka’s facility through these illustrations. It was only much later that I realised that this was the beginning of a new exercise to understand novels – to read into the setting and see how it interacts with characters.

This mode of reading was driven by curiosity during my college days, when I made an enthusiastic effort to cross-reference while flipping through novels like Anna Karenina and The Picture Of Dorian Gray. As I perused companion books and online articles to understand the settings better, I saw how literature branched into history, sociology, etc., connecting these disciplines in one text. For instance, while reading Tolstoy’s masterpiece, Anna Karenina, the knowledge of the gossip-mongering imperial Russian society helped in understanding what adultery had meant for Anna (but not for the men) during those times. In Dorian Gray, the juxtaposition of aristocratic society against industrial London highlighted a veritable power play amongst the classes. These histories course beneath the stories – like a hidden reference book that can be extracted by reading around the setting.

Reading Forgotten History

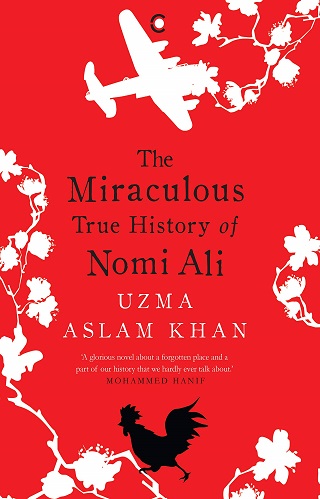

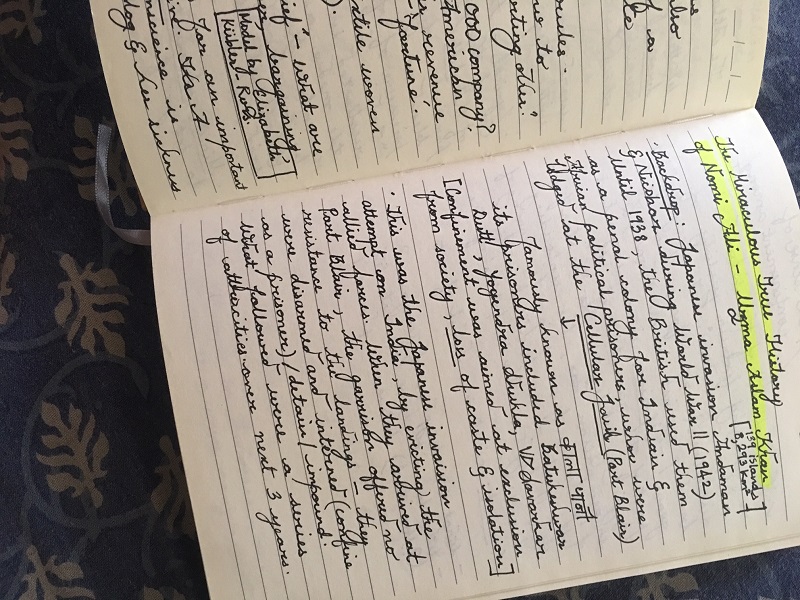

A form of this exercise can be demonstrated through my experience reading into the setting of Uzma Aslam Khan’s The Miraculous True History Of Nomi Ali – a prolific novel that delves into the annals of the Japanese invasion of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands during World War II. The story revolves around the local-borns – the convicts (and their children) brought in from different parts of mainland India to the penal settlement at the Kala Pani jail in the pre-Independence era. The events are witnessed by the adolescent protagonist, Nomi.

This setting in history has been ‘forgotten’, as the author herself states. Thus, it was important, for me, to derive information on the backdrop.

The exercise of reading into the novel’s setting involved availing a plinth of online sources on Kala Pani, the Japanese invasion of India and a Condé Nast catalogue on the beauty of the archipelagos. Understanding these elements glorified the impact of the novel, especially Kala Pani, which seemed like an ambient villain in Nomi’s story. Furthermore, comprehending the indigenous tribes, that have been widely discussed by mainstream media, was indispensable, as Khan subverts their narrative, giving the reader a wholly different perspective. She uses fiction to reflect upon those stories that never made it into our history books.

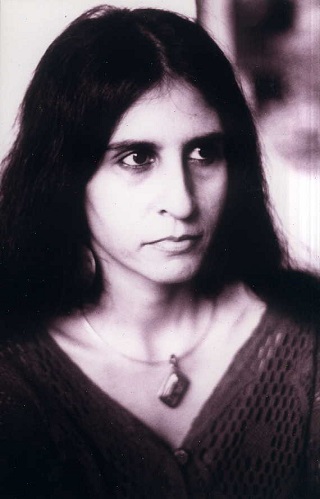

(Image via Wikipedia)

The Hidden Antagonist In The Setting

The Condé Nast catalogue helped me picture the novel’s setting. There are crystalline waters, birds of paradise, like the blue swifts, and cliffs from where sunsets appear like ethereal paintings. Khan explores the dreamy raw beauty of the islands through straightforward descriptions. However, the brilliance of her writing lies in juxtaposing the gorgeousness of the terrain against the misery of Kala Pani. The island’s allure cocoons the novel’s antagonist: ‘The jail. Shaped like a starfish and the colour of a wound’, which is seen ‘through the paduk trees on the summit of the next hill’. From this cliff, Nomi (while looking at the jail) ‘could see where she lived’, and the sea that ‘was so many greens and blues, all glassy and glittering’.

In a bid to discern the jail’s history, I revisited an article by The Guardian, ‘Survivors of our hell’, in which authors Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy have created a resonant picture of the atrocities committed on mutineers from India at Kala Pani during the colonial era. Khan takes the narrative forward in her novel by talking about the jail during the Japanese invasion.

After cross-referencing the history, I noticed how Khan built upon the prison’s legacy of torment that was handed over from one coloniser to another. Thus, in moments when Nomi, the adolescent protagonist, observes the jail and the guard ‘who has been looking at them with hundred eyes’ (an indication of how closely everybody was watched), it is upon us to understand what she is looking at – a century’s worth of inhuman acts committed inside the large prison. It is plainly tragic to comprehend what the protagonist doesn’t, that she has lived under this stealthy villain’s shadow all her life, with no hope of leaving the shore anytime soon.

(Image via Yash Raaj)

Stories Of The Marginalised

Khan uses the Kala Pani setting to bring out stories of the marginalised through fictional characters. This is mainly done through a nameless prisoner, who is only identified by her number, 218 D. Her storyline made me realise that we are only aware of the narratives of the popular prisoners jailed in Kala Pani. What happened to the lesser-known people who were torn from homes? These loopholes are bridged by Khan in Nomi Ali through the story of an anonymous convict.

Prisoner 218 D was born in Lahore and led a free life, until she was arrested for murder. Khan explores the psychological impact of the setting by showing how Prisoner 218 D loses her sense of self over the course of her trial, with her memory deteriorating further in jail. In one instance, Prisoner 218 D ‘stands against the wall (of her cell), as she had done in Lahore while waiting for the verdict. How long ago, she does not remember. If she could find the missing details, they might absorb her, at least for a while’.

Another part of my extra reading involved familiarising myself with the indigenous tribes of the islands, since they are characters in the book. The Andamanese settled on the islands 26,000 years ago. Today, they are branded as savages by the world, a label that was strengthened after an American was killed in 2018 by the Sentinelese. This casual branding across the media reeks of a colonial hangover. We still follow the coloniser’s perspective; a fact that Khan corroborates in her novel by mentioning what Lieutenant Archibald Blair thought of the aborigines. He said, they ‘could be cultivated’, but ‘does not know how’.

However, I realised Khan manages to subvert this perspective by building a glorious tribal setting. She shows the tribes as a community with a compassionate culture of their own. Towards the end, after Nomi survives a storm and washes ashore an island inhabited by a native clan, she is comforted by them. Nomi is witness to their ways of living, and how the women of the tribe were doctors who knew ‘which trees blossomed, and when, and how to turn roots and stems into medicine’.

These women heal her and then embark on a quest to reunite Nomi with her kin. The trajectory, for me, pumped the much-required humanitarian perspective on a civilisation that the world needs to acknowledge.

(Image via Yash Raaj)

I believe this manner of reading – be it understanding the core histories or even gathering new vocabulary – respects the cohesive effort that an author makes while weaving a setting.

For nearly two decades, this animated reading and recording of new information has made me run into multiple volumes of my reading journals. For an outsider, they may look like abrupt notes. However, these cross-references have helped me think critically and question the source text.

Moreover, this habit has brought out a new side to me as a reader. I have learned how to arm myself with information, which is highly necessary in an era of social media activism. Careful reading certainly adds an edge and displays a streak of awareness accumulated through literature.

Devourer of all writing, fly-by-night artist, consumer of so-bad-its-good cinema, editor for 'paapi pent', most at home on a sunny beach with cold beer, prawn curry-rice, and a four-pawed canine companion.

Read his articles here.