Essay

How The Setting Helped Fern Road Come To Life

‘Fern road is not a road lined with ferns. It is a labyrinthine lane, lined with practical, sturdy houses, two and three stories high. Their windows have wooden shutters, with columns of slats that open and shut like giant mechanical eyelids. The houses look like they’ve been here forever, their balconies floating above the narrow footpaths like magic carpets.’

Thus begins the story of Orko, an adolescent boy. When Orko’s mother was alive, he believed that he was going to grow up to be exactly like her; she told him that he was a boy, and that boys didn’t grow up to be women. After her death, Orko struggles with this truth, and the novel follows his journey as he navigates a labyrinth of confusing emotions and strange desires. If this story were taking place in the present day, Orko would have a multitude of voices in his support; he would, perhaps, have a community of young people who thought like him and felt the way he did. However, there would still have to be a reckoning — that frighteningly private investigation of one’s own identity. It is this reckoning that was of interest to me.

On Dysphoria

Dysphoria is defined as ‘a state of unease, or generalised dissatisfaction with life’. Gender dysphoria, then, is that sense of unease with one’s gender.

It would be nearly impossible to write this story without taking cognisance of contemporary conversations around gender dysphoria. When I tried to weave these conversations into the narrative, I found that the inner voice of my protagonist was somewhat diminished by the politics around the subject. There were questions — would Orko grow up to gender-queer? Transgender? Would he continue to be miserable all his life, pretending to be someone he wasn’t?

The earliest iteration of the story was set in the present day, and in it, I attempted to address these questions. The result was wholly unsatisfactory. The emotional content of the story was greatly diminished by its diagnostic component, and the narrative seemed to have been contrived in service of the diagnosis. I realised that I had erred by choosing a label, because it restricted me to a framework defined by that label.

(Image via Spectrum)

The Bildungsroman

I reimagined the novel as a coming-of-age story, of which gender dysphoria was just one facet. The story I had in mind was volatile and fluid, thick with questions that have no definite answers. I decided to start again, with the proposition that Orko was a young boy who would rather be a girl. This time, though, I decided that I would let the story find its own direction, informed by the social milieu in which my protagonist lived. There would be no diagnosis, no definition, no preconception of a happy outcome.

In order to shift the focus from the political to the personal, I decided to set the story in the late eighties — a time when the labels that I wanted to avoid had yet to gain wide recognition. I arrived at this period quite naturally, because it was during the late eighties and the early nineties that I was discovering the fragile, hazy contours of my own identity.

I wrote at a furious pace, not allowing myself the chance to read the manuscript in its entirety until it had grown to 40,000 words. This iteration unfolded in Calcutta, but Fern Road did not feature in it. I was proud of what I had achieved: half a novel, in six short months.

Upon reading the manuscript, I realised, yet again, that I would have to throw it all away. The prose reflected the time in which I lived — frenetic, edgy, indignant. The vocabulary was entirely unsuitable for a novel in which the only perspective was that of a 15-year-old boy. The markers of time and period were shallow and lifeless — the languid, understated Calcutta of the 1980s was nowhere to be found.

I was at an impasse. I briefly considered abandoning the project, but the story kept rattling about in my head. I began to take walks that consumed entire afternoons. I thought about writing and I read about writing, but I wasn’t writing at all.

Fern Road

Fern Road is a narrow lane, lined with two- and three-storey houses that look like they have stood there forever. The lane begins on the fringes of Gariahat market, one of the busiest in southern Kolkata. It winds through a quiet residential neighbourhood and emerges near Golpark, which is an important waypoint for the public transport systems of the south. There are no signs of opulence on Fern Road, nor of abject poverty. While many neighbourhoods of its vintage have seen old houses being torn down to make way for modern blocks of flats, Fern Road remains largely untouched. Even the doctor’s chamber and the lawyer’s office there are from a bygone era, accommodated in quarters that used to be living rooms, marked by faded lettering on signboards weathered from years of exposure.

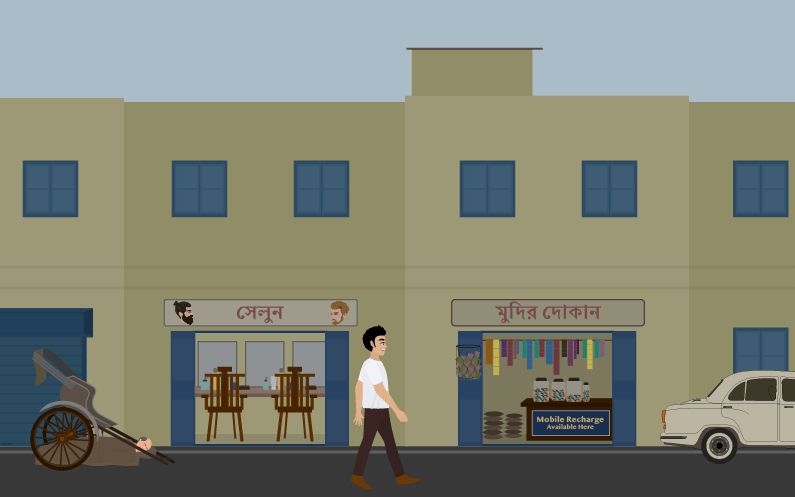

I rediscovered Fern Road during a post-meal walk on a winter afternoon. I remembered walking down the lane when I was 12 or 13-years-old, to Gariahat, with my grandmother. In retrospect, I can only say that it was serendipity that found me there, almost 30 years later. It was an exceptionally quiet afternoon. The stodgy old houses crowded around me, making me feel as though they were scrutinising me through their slatted windows. I was astonished by the fact that so little had changed; the only discernible markers of the present day were a defunct cyber-café, a flat-screen TV seen through a living-room window, and a signboard advertising mobile recharges affixed above the door of an old-fashioned grocery shop. Some images from that afternoon are still vivid: a man sleeping under a rickshaw; a fair-price outlet with half-downed shutters; an old-fashioned barber’s shop with a bright blue door; a rusty Ambassador, the colour of a withering plantain leaf, parked in front of a gnarly house that evidently belonged to a doctor.

That night, I wrote a few short paragraphs describing Fern Road and its by-lanes. I read the paragraphs a week later and was surprised by the indolent cadence and the subdued tone — it was unlike anything I had written before. Many of the paragraphs have found their way into the novel, virtually unchanged; the style I discovered while writing them has been deployed in the chapters that reveal Orko’s character and his circumstances.

***

Fern Road, to me, will always be the magical mnemonic that helped me reclaim sparkling memories of the city of my childhood. I have used these memories to construct the setting. It took two years to complete the first draft, and during those years, I returned often to the neighbourhood, with my protagonist, seeing the world through his eyes. While it would be a stretch to assert that Fern Road of the 1980s is essential to the story, it can safely be said that it lies squarely at the heart of the novel.

Angshu Dasgupta is fascinated by words and their meanings, and has an irrational weakness for syncopated rhyme. He began writing while in college, inspired by the words and the music of Joni Mitchell. His first novel, Fern Road, was published twenty years later. Angshu lives in Kolkata, with his spouse and two teenage daughters. He is a computer programmer by profession. He can sometimes be found riding a motorbike in the Eastern Himalayas, all by himself.

Read his posts here.

Fascinating to read about the successive iterations of the novel, and the locale that engendered the tone of the final version.

I find setting crucial when I write, as well — unless I can intimately visualise the setting, I can’t see my characters move about in it; so, the setting fundamentally shapes my characters and my story.

Also insightful to understand the reasoning behind your choice of era. From your description, it seems a sound choice to have set the novel in a time when the plot could follow the protagonist’s unstructured evolution. I’ve not read a novel about identity politics — but, after a few years of listening to people agonising whether they are “polyamorous” or “demisexual,” this jargon-free exploration seems a refreshing break from today’s jargon-dense, paradoxically regimented exploration of identity.