Essay

My Problem With Indian Diasporic Writing

On my first visit to a local library in America, I wondered if I was in reader’s heaven. Tall shelves stacked with books I could take home for free! Until then I had managed to satisfy my voracious reading appetite with the meagre selection in the school library, supplemented by books acquired from second-hand bookshops in Mumbai. Upon receiving my driving license, instead of the temple, I first drove to the library. Within months, I had finished reading several popular and upcoming American authors.

In subsequent years, I spent more time in the laboratory than the library. My education happened within and outside the walls of the university. I began to appreciate America’s comforts and conveniences without comparing it to India. Instead of differences, I found things in common with students, colleagues and sometimes, even strangers. I stopped seeing myself (and others) as foreign and saw them as fellow humans.

Unknown to me a subtle shift had occurred. I had gone from feeling alien to feeling at home in America. But there were days when I wished I was back in India. I wondered if Indian writers in America had captured this strange dual existence that is the burden of immigrants. I returned to the library, eager for books to reassure me that it was perfectly natural to feel homesick during Diwali, to feel awful while missing major milestones of family members back home and to mourn the loss of friendships due to the constraints of distance, time zones and technology, despite feeling outwardly content, thriving even, in the country which was now home.

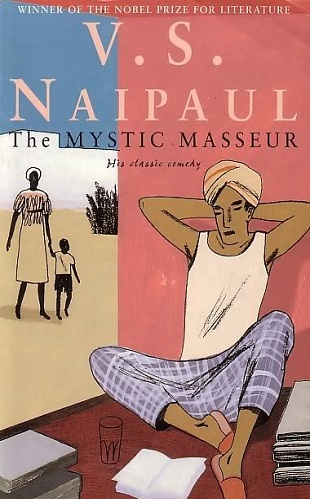

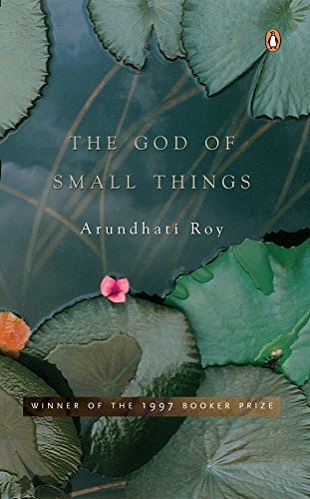

Despite the spread of the Indian diaspora and its deep roots in America, the literary offerings were limited. While Arundhati Roy had taken the world by storm with her fully Indian novel, The God Of Small Things, authors of the diaspora still continued in the trail of V.S. Naipaul’s Mystic Masseur with exotic stories that featured regular Indians with supernatural abilities and spices with healing powers. Movies had not moved very far either; from City Of Joy, to Slumdog Millionaire, the formula and fixation on exaggerating the third world stereotype of India remained in place.

My NRI peers and I went to work every day, navigated traffic, and managed our homes. We did not possess magical powers, nor were we protagonists of those rare success stories of people who rose from unimaginable poverty and deprivation. Despite our suave exteriors, our predictable, mundane lives remained submerged in the ethos of our Indian upbringing. How, then, did we make sense of our place in the world? How did we define belonging? Most importantly though, where were our stories?

I decided to follow Toni Morrison’s advice – ‘If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.’

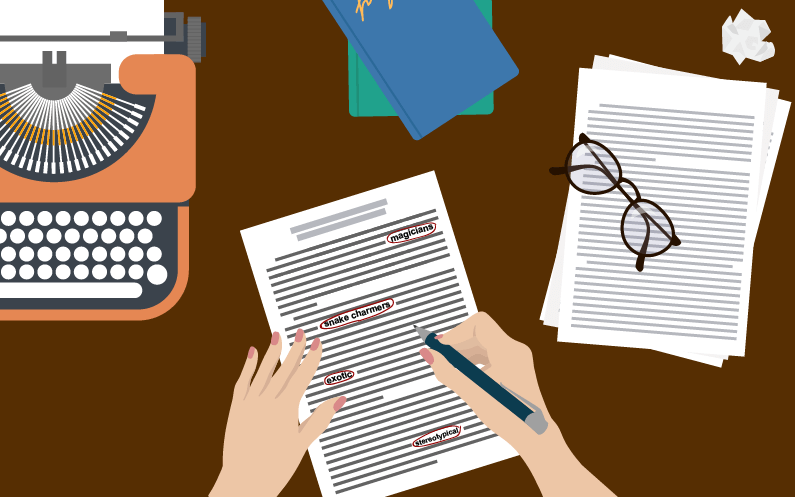

My writing was not a nostalgia-fuelled narrative focussed on all that was missing in the country that was now home. I wrote stories that reflected my life. As a new mother, I observed how cultural nuances impact a universal experience like motherhood. On the other hand, my struggle to balance my personal life while working full-time was one that was common to most of my colleagues, irrespective of the differences in our cultural heritage. I wrote as a woman managing multiple roles and labels, including ‘NRI’. My writing was a genuine exploration of life as I lived it, with no room for magicians and snake charmers.

When I sent my writing out to literary magazines in the U.S.A., I learnt that such narratives were not welcome in the mainstream publishing industry. Rejections were disheartening because I was unable to join the conversation in the place I lived. By not writing exotic or stereotypical stories, I denied myself a seat at the table. And without the balance and counterpoint offered by my views, the danger of the ‘single story’, so eloquently articulated by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, continued.

After 14 years, I returned to a revitalised literary scene in India. A generation of readers swore by Chetan Bhagat’s simple, contemporary stories sold in pocket-friendly paperbacks. But these stories did not satisfy my hankering for beautiful writing that had depth, dimension, and literary merit.

Instead, I read fiction by Shashi Deshpande and Anita Nair. Their stories were authentic reflections of life in India. It satisfied the ‘desi’ in me, but I craved writing that had Indian characters inhabiting a wider canvas not limited by the Himalayas on one end and Kanyakumari on the other. Perhaps, like most readers, I was looking for protagonists who resembled me, both in their ethnicity and in their life trajectory.

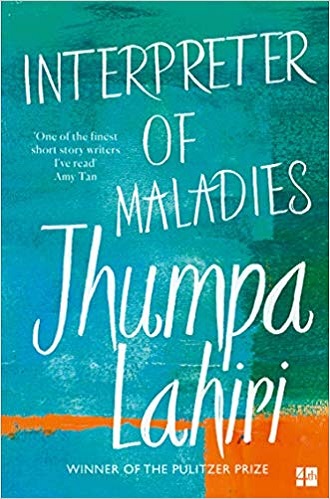

Enter Jhumpa Lahiri. Impressed by her debut Pulitzer prize-winning short story collection, The Interpreter Of Maladies, I hoped I had found a ‘favourite’ Indian author for life. But with The Namesake and subsequent novels, her writing drifted away from having any relevance to me. The portrayal of the immigrant couple in The Namesake as insular and close-minded characters, implying that all who move to another country live in their own physical and mental ghettos, did not come across as an authentic or balanced representation to mee.

In Lahiri’s own words, her choice of the Indian-American experience as her subject was motivated by ‘…the desire to force the two worlds I occupied to mingle on the page as I was not brave enough, or mature enough, to allow in life.’

I picked up writing again; this time I wrote about returning to India after spending my early adulthood in America. My column appeared in India Currents, a California-based magazine. I received emails from readers each month, telling me how my story had validated their doubts, given them the courage to make the right decision and most importantly, assured them that they were not alone.

Given the influx of returning NRIs at that point in time, I expected my words to resonate with a larger audience. But there wasn’t any interest among Indian publishers. Perhaps it was because I wasn’t a well-known author. Perhaps the business case was not strong enough to compete with authors who were mining Indian mythology and successfully packaging it with a contemporary twist. My essays remained buried within the pages of a print magazine.

After spending a decade in India, I moved to Singapore. Moving in midlife is not the same as migrating as a young adult. My motives are different, as are my expectations. Maturity and hindsight allow me to look at my current experiences with a broader perspective. I am reluctant to stereotype people or attach labels. I refuse to divide people along the lines of colour and community.

As a lifelong reader, I have enjoyed the stories of people set in places and situations very different from my familiar environment. Diverse stories add variety to the mix. They also serve a greater purpose by stripping the exotic nature of people we perceive as ‘others’ by shining a light on what is common – our shared humanity.

I continue to write, following a process that is the obverse of Lahiri’s. I occupy two worlds, but my worlds mingle daily, and sometimes collide, in real time. As I continue my search to find my place in a world not limited by geographical borders, I am aware of my unique vantage point as a ‘two-time NRI’, lodged in a middle place from which I can watch the world.

I submit my work to publications that seem receptive. When a rejection arrives, it serves as a springboard for me to write more, write better, and explore other avenues. In discussions with other writers whose backgrounds and life experiences mirror mine, I found kindred spirits who have continued to document their stories despite not finding a receptive outlet to take these stories to the larger reading public.

In the 30 years since my first international flight to America, much about me has changed, as has the world around me. I no longer crave approval from publishers who slot writers into boxes, showcase those who validate their biases or amplify grievance-based, divisive narratives. When editors bow to marketing gurus and choose content that sells over quality writing and storytelling, it is a great disservice to readers and makes it difficult (if not impossible) for writers to break in.

I do what I can. I write, revise, polish. I continue to send my writing to traditional publishing outlets. Some of my work appears in blogs, social media platforms, online publications and anthologies.

The high point in recent years has been the advance in technology that makes it possible to self-publish. A fellow writer and I spent years discussing our dilemma but now we have decided to act on it. With our fledgling enterprise, Story Artisan Press, we have entered the self-publishing marketplace. Our vision, summarised in three words – Every Story Matters, makes it more than just a channel for our own writing. It involves bringing into existence, and to the attention of readers, thoughtful and thought-provoking writing, open to all writers, whether within India or outside.

—

Our readers today may be few, but I know our tribe is much bigger, spread out over countries and continents. They are not just NRIs but all who move out from their familiar places and seek to belong in the places they have defined as home. To my delight, I now have the tools to create my own kind of writer’s heaven, one that is suspended between many worlds but remains connected to all.

Ranjani Rao is a scientist by training, writer by avocation, originally from Mumbai, and former resident of USA. She lives in Singapore with her family and is presently working on a memoir. She is co-founder of Story Artisan Press and her books are available on Amazon.

You can read her articles here.

A great piece, nicely structured and presented. The writer does a great job of presenting her own story while making a significant social/literary comment. Good combo indeed.

Thanks for the encouraging comment, Asha.

Ranjani, Nice article. I am a fellow writer from Calcutta originally, now in California. I have similar experiences like you. Just published a historical fiction in young adult genre Shadow Birds — Story of a young girl during the Partition of India. Now working on a fiction piece in the Women’s Fiction genre..about a young bride who tagged along with her husband’s dream catching all her life the comes across at a crossroad where she has to make a choice. I think I don’t need to explain more but it would be nice to keep in contact if you wish. My authors page in Face book is under Anindita Basu writer. And blog http://www.aninditaswritingright.blogspot.com.🙏

Anindita – thank you for sharing your thoughts. Look forward to staying in touch with you. Do check out Story Artisan Press page on facebook.

This was an excellent article. Like you, I find it difficult to relate to a lot of Indian diasporic writing which seems to pander to stereotypes to secure a market. Of course this could also be said of books like The God of Small Things which provides many insights but also as Ruth Vanita pointed out perpetuates the stereotypes of an inexorably hidebound society and universally downtrodden Indian women. Like you, I also decided to self-publish. My first novel The Rose and the Thorn looks at revolution and reform in colonial India from the point of view of so-called ‘ordinary’ women. It has been quite well received by both Indian and other Australian writers (I live in Brisbane), and I am inspired to write the next one.

I look forward to reading more such excellent articles from you.