Essay

The Problem With Monster Stereotypes In Literature

Monsters abound in children’s stories, and they must. Rephrasing Neil Gaiman’s words on the importance of fairy tales, one could say we need monsters not just to show us that wickedness exists, but also to prove that wickedness can be vanquished. However, the messages literature conveys through monsters need to be investigated time and time again.

The Creation Of Monsters

At a Writers’ Club I conduct for pre-teens at a school in Pune, we often play versions of a monster game. Inspired by an activity I came across online, I invite children to create a monster together. I usually begin, “The monster was thirty feet tall …”

The children soon get into the spirit of creation. They let their imaginations go wild and come up with ugly, beastly creatures that want to take over the world. As they do this, a few things emerge –

- The monster is “fat and ugly”;

- The monster is nearly always black;

- The monster is male.

Are any alarm bells ringing?

Human beings are diverse, and literature has worked hard at creating a range of characters from stunningly good-looking villains, both male and female, to protagonists who are not physically beautiful. This variety extends to human-like characters, too. We have beautiful, wicked witches and ugly, good wizards, plus everything in between. This diversity is crucial to the age-old good versus evil battle, but the journey ahead remains a long one. Nothing makes this more apparent than monsters. The monsters children create show us that stereotypes, instead of disappearing, have just been pushed deeper into our sub-conscious thanks to our attempts to be politically correct.

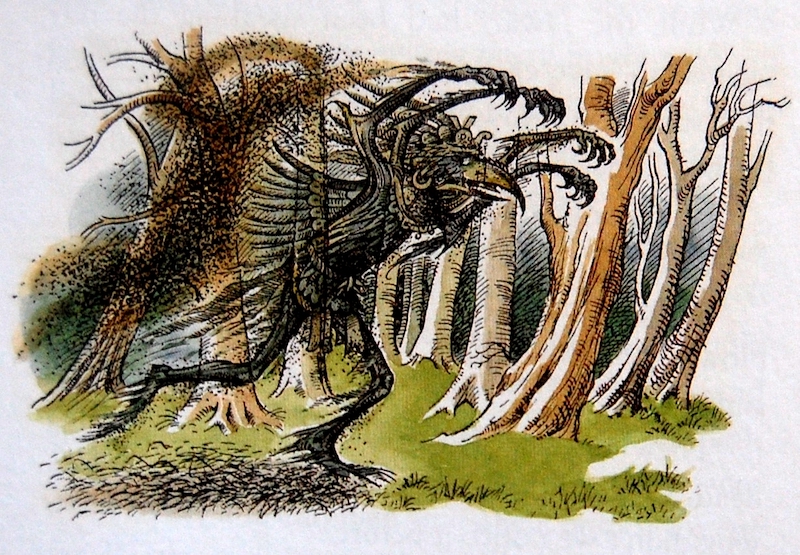

(The monster from Moin And The Monster via Desi Writers Lounge)

Monsters In Literature

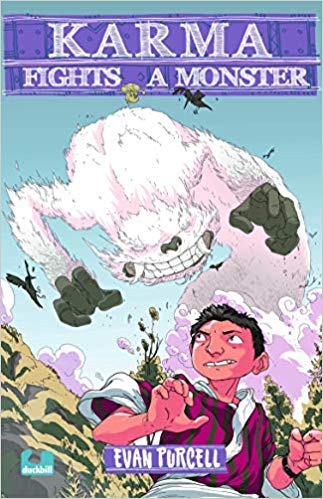

Picture books and fairy tales form the bedrock of how we imagine monsters. Recently, I read Evan Purcell’s Karma Fights A Monster, and my heart rejoiced for here was a monster I longed to see in children’s literature. I picked up the book because I was intrigued by the frightening white monster on the cover. Especially as the popular imagination of children is often constructed by illustrations rather than text, I found the whiteness of the monster particularly relevant. As I read on, I continued to be delighted by Karma Tandin’s first adventure. For one, I loved the fact that the main monster is female—we need modern female monsters. Secondly, the monster’s physical appearance is unique. While the idea of deception, which is often associated with monsters, remains, Miss Charmy, when she removes her human guise, reveals that she is a shark, rather than a fat, ugly creature. Most wonderfully, there is a moment when Karma realises that looking scary is not a crime – and this is an important step towards breaking the link we continually build between character and appearance.

Another delightful monster is the nameless one in Moin And The Monster, for it is neither masculine nor feminine. The monster finds the distinction between the two silly. Yet, a question that came to mind as I read the story was, once again, about skin-tones. Often, lighter-coloured monsters are less frightening, bordering on harmless and funny rather than dangerous. Can a pink monster be at all scary? Must it be darker to create terror? Surely not, for ghosts are white. Yet, does the fact that the monster finds pink funny rather than fearsome reflect our own conditioning?

Conditioning begins with the very first picture books we read. Most illustrations of death and the devil in childhood tales are black, male and scary, while angels are white. Rakshasas and asuras in comics spring to mind – pot-bellied and dark-skinned. Asuras like Maricha appear like black clouds. I am also quick to point out that pictures that portray rakshasas as blue are typically euphemistic, for blue stands for the darkness of a thundercloud, and yes, a thundercloud is black.

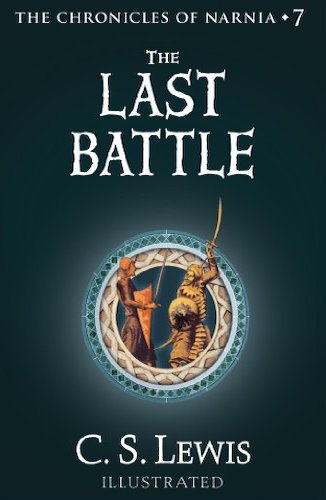

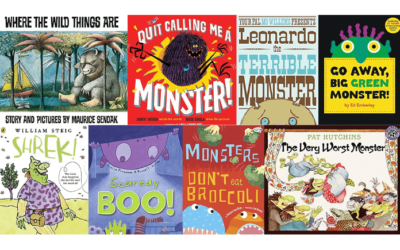

Moving away from the Indian context, in The Last Battle, the final book in the Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis describes the monstrous Tash as the colour of smoke. As the narrative moves on, Tash, the false god, is described as a horrible Monster, an evil grey creature, worshipped by dark men with beards, in contrast with the golden Aslan, followed by fair-headed Narnians. Deceptive and treacherous, Tash is the one who leads people away from the true path.

Tackling The Monsters Within Us

Monsters and humans bring out two sides of our relationship with political correctness. The idea of being politically correct is itself, of course, debatable. How far should we go? When does political correctness overlap uneasily with censorship? These are questions that could find beginnings of answers here, for I am trying to challenge the very foundation of this correctness.

When it comes to addressing issues like stereotypes in literature, it is easier to be careful with human and human-like characters. We try to be inclusive and diverse, and usually, pat ourselves on the back when we do so successfully. We slip up occasionally but, all in all, we know what we ought to do. I would go as far as to say we know how we ought to think.

It’s monsters that have the potential to bring out the monsters hiding within us. They delight in pulling us into depths that we rarely, if ever, acknowledge.

When we create fat, dark monsters, we reveal the subtext of our understanding of inclusiveness: that equating fatness or dark skin with ugliness is “impolite”. In this way, we clearly shift the problem from deep-rooted prejudice to a superficial issue: behaviour. To ensure that children don’t call fat people ugly is like treating the symptom, not the disease. The problem is not calling people – dark or fat or anything – ugly; the problem lies deeper: in perceiving people as ugly based on nothing but conditioning.

We feed into stereotypes when we describe monsters primarily as huge, ugly giants or stupid, fat trolls. We convey the idea that ugliness is equated with untrustworthiness. Let’s not forget that notions of beauty and ugliness are shaped by an ableist world full of prejudice.

Additionally, even in modern literature, most ugly monsters continue to be male, as if girls have a greater need to be beautiful. More leeway is given to boys, for it is understood that they will play with dirt. They are allowed to get filthy. Meanwhile, girls continue to internalise a greater responsibility to be good, the corollary of the age-old ‘boys will be boys’. Let me be quick to add that girls don’t always feel they are getting the short end of the stick here. Some are only too happy to be ‘holier than thou’.

(Tash from The Last Battle via Narnia Fandom)

However tempted we are to say that ‘not all’ boys or girls act a certain way, or ‘not all’ scary monsters are fat and dark-coloured, a counterargument like this shifts the focus away from even recognising that a problem exists. Monsters continually bring out the undercurrent of how we link ugliness, as understood by society, to villainy. Gender stereotypes, body shaming, racism – these become blatantly obvious when we move out of the political correctness associated with humans and into the realm of monsters.

And this leads to conversation. When children see pictures of people with various skin tones, who are they more likely to trust? A fat clown and a thin clown – who is more ‘deserving’ of ridicule?

Teaching children – or adults – theories and ideas about stereotypes often becomes preachy and redundant. We all think we are woke enough to understand political correctness and socially appropriate behaviour. When we bring monsters in, we start conversations once more.

Varsha Seshan is a writer of lists, emails, detailed notes to self and children’s books. She has written 15 books for children and has twice been shortlisted for the Scholastic Asian Book Award. When she is not writing, she is usually travelling, working with children or dancing. She conducts reading and writing workshops for children and adults at schools and libraries. She also facilitates a writers’ club for pre-teens at a school in Pune (India), where she lives. A classical dancer with over 25 years of training in Bharatanatyam, she has performed extensively in India and abroad. Find out more at www.varshaseshan.com

Read her articles here.

that equating fatness or dark skin with ugliness is “impolite”.

I’m sorry but this is where I stopped reading what was a wonderful article. Equating fatness or skin colour with ugliness is not impolite, not talking about it is not polite. Equating fatness or skin colour with ugliness is downright insensitive and rude.

Your readers obviously have a good command over the language to understand what impolite means and how it is differs from insensitive and rude.

Hi, Awanti, thanks for your comment! I do go on to say something similar to what you say here, and I take it one step further. The double quotes (for “impolite”) are to indicate that I’m quoting parents here. “Impolite” is the very notion I wish to challenge. While I agree with your point, here’s what I’m trying to put forward, and why I call the idea of impolite the subtext of inclusiveness as it is (unfortunately) taught.

When children are taught not to make comments that equate body type and colour with ugliness, they are often told that it is “not a nice thing to say”. Both here and in the article, the double quotes stand for what parents frequently tell children. In my opinion, though, the “say”ing, though important, is not the root of the problem. Perceiving a link, or believing that a link exists, is the problem. And that is why, though I agree with you that it is insensitive and rude, I want to take this one step further — that the perception itself needs to change. Fat does not equal ugly. Dark skin does not equal ugly. It is not just insensitive to say this; it is problematic to see it.