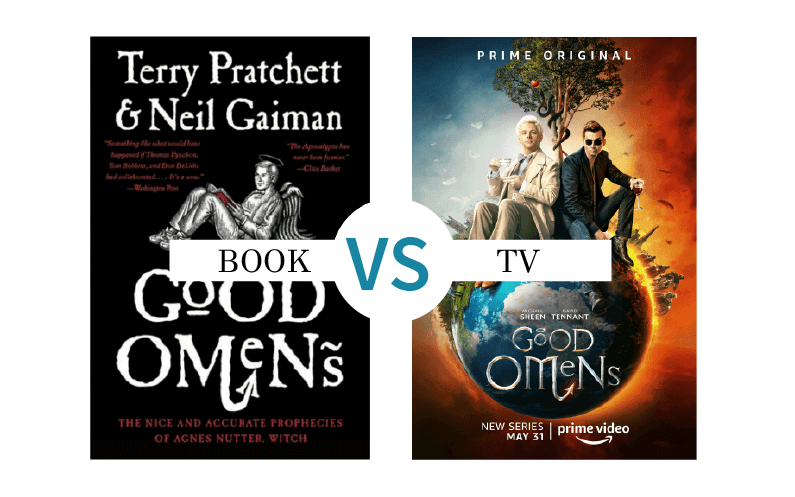

Book Vs. TV Show

Good Omens

Adaptation ScoreThe adaptation score is a scale used to measure the accuracy of the book’s adaptation into a movie. It is not a score which judges how good the book or movie is: 7/10

It has taken about thirty years for Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett’s 1990 fantasy novel titled Good Omens: The Nice And Accurate Prophecies Of Agnes Nutter, Witch to be adapted for the screen. Fantasy is a challenging genre as it is – elements of world-building have to collapse perfectly into real-world myth and folklore. Transforming an epic and fantastical novel like Good Omens into a miniseries, therefore, was no ordinary task. But Neil Gaiman has done this before: Amazon Prime’s Good Omens is his third venture into adapting his books into miniseries; Starz’ American Gods and Netflix’s Lucifer are the other two.

An Adaptation That Almost Never Came – Like The Armageddon

Gaiman and Pratchett always wanted to make an adaptation of Good Omens. In an interview, Gaiman talks about how several years after the novel was published, he and Pratchett spoke about the various ways they could have brought in some flavour into the storytelling: since 1991, they spoke about adding in more angels and re-visiting Heaven and Hell within the storyline. One of their ideas was to mould the book into a film for a wider audience and to also incorporate newer ideas that they had for the evolution of the plot.

In 2002, Terry Gilliam, the director of 12 Monkeys, attempted to start the film, but these plans were thwarted by anxieties arising from the 9/11 attacks. Gaiman said, in an interview – “[b]ut it was post 9/11. No one was interested in an apocalyptic comedy”. In 2011, Terry Jones declared that he would “shepherd” Good Omens into a television series but this plan fell through, and Gaiman and the original Terry (Pratchett) decided that they would develop a miniseries on the book. By 2014, however, Pratchett’s Alzheimer’s – or Embuggerance, as he lovingly called his disease – grew worse, and he sent his co-author a letter that Gaiman holds close and regards as Pratchett’s last request to him – “I’ve never asked you for anything before, and we’ve always agreed that with anything related to Good Omens we either do it together or we don’t do it. But you have to do this. No one else can do it. I know how busy you are, but I want to see this before I can’t see anything.” The rest, of course, is history. Pratchett passed away in 2015 but Good Omens was adapted to the screen.

Keeping The Spirit Of The Text Alive

In many ways, Good Omens – the series – is a great rendition of the book because it welcomes both fans and newcomers with the same enthusiasm. The story, as originally devised by Gaiman and Pratchett, is about a demon (Crowley) and an angel (Aziraphale) working together to stave off a looming Armageddon and save the earth. What happens in over 400 pages in condensed into six episodes, all crafted by Gaiman himself.

And what makes Good Omens, the show, extremely riveting is the fact that it is both enjoyable and timely: the end of the world is a real possibility now, as it was thirty years ago. The book’s promising hopefulness and ecological consciousness that worked well against the background of the Cold War and the threat of depletion of the ozone layer has been translated so effortlessly into the show. A line from the book such as “your polar ice caps are below regulation size for a planet of this category” can be adapted into the screenplay of the show because against the backdrop of the climate change protests, it rings true.

While keeping the show relevant, Good Omens preserves the spirit of the text in a very wonderful way. The screenplay holds onto a lot of the characters and dialogues and gives into the weighty descriptions within the book. As each scene gives into the next, it feels like turning the pages of the book itself, and uncovering the remarkable world that both authors have built. Even the end credits feel like the end of a chapter.

(Image via Inverse)

What Works And Does Not In The Adaptation

The leitmotif about Queen’s greatest-hits CD mentioned in the book has been brilliantly adapted into the show. When Gaiman and Pratchett wrote the music into the plotline, it was a take on the inescapability of the grandiloquent music from the 1980s. The theory behind this was that any cassette left in the car long enough would turn into the best of Queen – “All tapes left in a car for more than about a fortnight metamorphose into Best of Queen albums”. What was written as a joke on the times, translates beautifully into a plot-device, in providing layers to Crowley’s character – it is almost perfect when Crowley’s Bentley pulls up during the first episode and we hear “Beelzebub Has Put A Devil Aside For Me”. It is hilarious when Crowley drives through London’s inferno to the tune of “I’m In Love With My Car”. Each important moment in the show features a significant song by Queen – Pratchett would have perhaps been doubly proud of this part of the screenplay.

Besides this, obscure but humorous details that readers love about the book made it into the miniseries. For instance, the book’s expository narration by God – a woman, and played by Frances McDormand – was a magnificent way to keep the essence of the text alive. Details such as the Earth’s exact birthday, it’s zodiac sign (Libra), and how God “moves in extremely mysterious, not to say, circuitous ways” are all wonderfully portrayed in the show.

Some bits were adapted to the recent times, though – Crowley, in the miniseries, brings down the whole London mobile network (much to his own chagrin, because he cannot make calls!), as opposed to the Crowley in the book, who messes with the London cable network. There are also omissions and additions in the making of the series. Archangel Gabriel’s character did not occupy so much real estate in the book, but Jon Hamm’s comic timing brings a certain depth to Sheen’s reluctant acquiescence to the bureaucratic machinery of Heaven, with its exhausting approvals, meandering paperwork, and intense red-tape. The omission of details on the Them (Adam Young’s friends) and their friendship is a big blow to the plot; the Antichrist and his friends, and even the apocalypse remain secondary to the demon and the angel. Adam’s attachment for Tadfield is erased but Tadfield’s “optimal microclimate (…) the kind of weather you could set your calendar by” is retained.

(Image via The Verge)

Crowley-Aziraphale Friendship Casts A Shadow On Other Characters

What the miniseries does well is showcase the relationship between Crowley and Aziraphale – like two long-lost friends; like an old couple – their interdependence growing and showing in each episode, as the world crumbles around them. Their 6000-year-old friendship along with a backstory that spans various centuries and world events – Noah’s Ark, Nazi Germany, the Reign of Terror – is an addition to the miniseries, that certainly enhances their character sketches. Both Michael Sheen and David Tennant are perfect as the cultural aesthete and the insouciant fallen angel; like old friends, they talk about their work, dine at the Ritz, and generally discuss the difference between good and bad. All this and working together to stop the apocalypse slowly help Aziraphale and Crowley, who were initially on opposing teams, to grow very fond of each other.

The problem, of course, with magnifying the plot around Aziraphale and Crowley, amongst many others within the book, is that the miniseries forgets to explicate other characters’ backstories like those of the prophetic witch, Agnes Nutter (she features only in a handful of scenes) or her descendant, Anathema, or the Witchfinder’s Army or the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The other plotlines, when contrasted with the Aziraphale-Crowley friendship, seem to fizzle out, and non-readers don’t have a lot of context on why they are so important in fending off Armageddon.

This is perhaps a failure of the adaptation – people who have not read the text would not truly understand the value of the other characters in the overall plot. Readers of Good Omens will also lament that most characters don’t make it into the miniseries, or that some loose ends remain and parts of the screenplay are stripped of the literary pleasure of the original text. The ending, too, feels abrupt and anti-climatic as Gaiman writes an additional twist for the miniseries – both the demon and the angel have been kidnapped by their celestial colleagues and sentenced to death.

(Image via Variety)

In the larger scheme of the things, it is extremely difficult to say whether the book was better or the miniseries, especially because both were created by Gaiman (and Pratchett), or even if the adaptation was faithful to the book. As John Green says – “the book is different from the movie; it has to be. I don’t think there is something called a faithful adaptation because you’re turning scratches on a page into visible humans speaking audible words.”. Moreover, there are things that are possible with a miniseries – it reaches a wider audience and often, with such outreach, it is challenging to think exclusively of the readers. The makers of the miniseries had to balance the concerns of the readers with the need to reach a much larger audience, and this is where, in my opinion, Good Omens has bested other adaptations. It has won the hearts of many with the story of an unlikely friendship between a demon and an angel, and the meeting of good and evil at the end of the world.

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.