Excerpt

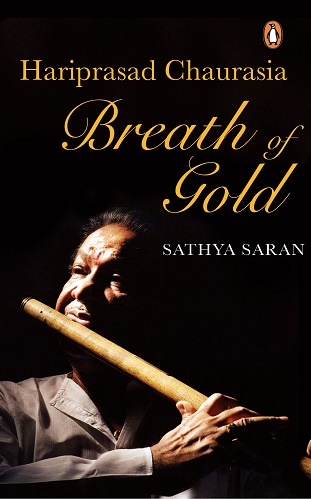

Breath Of Gold: Hariprasad Chaurasia

Oportunity favours the true of heart. He makes friends easily anyway, and shares with them his dreams, his fierce love of music. Bombaywallas are renowned for living private lives: the long commutes most find they must necessarily undertake, and the mixed bag of communities the city throws together, make almost every man an island unto himself. Yet, there are exceptions. Hariprasad finds one such in Ahmed Darbar, who also works at the radio station. One thing leads to another, and soon our flautist is busy every evening, playing his flute through the two-hour-long Gujarati plays directed and produced by Irani seth (Faridun Irani), for whom Darbar moonlights, composing the music. Hariprasad does not know it then, but he is not the only one dreaming. Irani’s daughter, Aruna, too dreams of a role in Hindi films, and eagerly auditions at studios by day, returning in time for make-up before taking up her role on stage in the evening.

Hari-ji believes it was one of his morning renditions over the radio that changed his fortunes forever.

‘One day, the studio got a call asking for Hariprasad Chaurasia, flute player,’ he recounts. ‘So I am called to the phone, and I take the receiver and lift it to my ear wondering who it can be, hoping

it is not bad news. The voice at the other end introduces itself as Master Sonik. “Can you come to the studio?” he wants to know. I am surprised. But I understand that he is an assistant with the music director Madan Mohan, and they are waiting to record, but their flautist has not come. And they want me to go there. I say, “I don’t know my way, I am new,” and he tells me he will pick me up. I was of course keen to meet music directors. I heard Lata-ji was singing the song . . . I went.

‘When I entered the studio, all turned to look at me in my dhoti and kurta. I got nervous. Many of the instrumentalists were obviously Christians, wearing pants and shirts. They stared at me. Then I was asked to play. I played my flute. Lata-ji was there, she looked at me when she heard the sound. Perhaps she recognized the sound.’

It was not the first time Hariprasad was entering a recording studio that was recording for a film. Often, in his interviews, he has said that the first song he recorded was for Lata Mangeshkar, who sang ‘Main to tum sangh nain milayke, har gayi sajna’ from Man Mauji, a song whose tune he remembers well enough to hum too. But that recording was much earlier, during a previous trip when he had come with other Oriya artistes to record an Oriya song. He had interacted with the singer then, whom he admired hugely, and asked her for advice on how to join the industry. Then, recording over, the group had gone back.

This time, the orchestra he takes his place in will support not Lata Mangeshkar, as he had hoped, but singer Talat Mahmood as he sings a ghazal. The film is Jahan Ara, which would be released in 1964. Based on Emperor Shah Jahan’s daughter, it weaves a story around the sacrifice of her love so she can look after her father thanks to a promise she has given her dying mother. Bharat Bhushan, star of many historicals and films centred on musical legends, plays the role of Mirza, the thwarted lover who expresses his pain through some of Madan Mohan’s sweetest compositions with lyrics by Rajinder Krishen.

The song that is being recorded is one such plaint . . . ‘Phir wohi shaam’.

If Hariprasad looked towards the singer who had also turned to see the flautist coming in, and hoped that Talat Mahmood would recognize him, his hope was belied. They had met during a recording, when the singer had recorded an Oriya song at the Cuttack radio station, and Mahmood had remarked on the quality of the flautist’s playing, adding that he should try to come to Bombay and find a place in the orchestra in films. ‘I could see he had no memory of having met me,’ Hariprasad says of this second encounter.

But there is no time to ponder over the past. It is time to rehearse and record. ‘Master Sonik gave me my cue sheet with my part in it, and asked, “Can you follow this?” I said yes. And we started.’

The flute comes in right at the prelude to the song, ‘Phir wohi shaam’. It continues to play softly almost right through, intermittently adding pathos to the singer’s voice as he laments over his loneliness without his beloved. In the interludes, it is sometimes heard singly before it blends in with the rest of the orchestra. ‘I played wherever I felt the mood was right and my flute was needed,’ Hariprasad says, reminiscing about that first recording.

A lesser artiste might have earned a rebuke for straying from the score sheet. But such is the tenor of his playing that the music director takes notice. ‘After the recording, Madan Mohan said, “Let him stay back. He must be present at every session, whether or not he is required.” I think my playing was a sensation, something new,’ he adds, eyes twinkling at the memory.

Just to mention a coincidence, Aruna Irani, whom Hariprasad saw most evenings on stage in her father’s theatre production, also had a role in Jahan Ara. And, some years later, Master Sonik would form his own music team with his nephew Omi, and they would compose for films under the name Sonik–Omi. Among them were Dil Ne Phir Yaad Kiya and Mahua. Hariprasad’s flute would find place in most of their compositions.

Best known for her long association with Femina, which she edited for 12 years, Sathya Saran is also the author of a variety of books. The Dark Side reflects her love of the short story, while her critically acclaimed biographies of S.D. Burman, Jagjit Singh etc. bear testimony to her love of cinema and music. Passionate about writing she recently held the first of its kind Writers Conclave titled The Spaces between Words at Kaladham near Hampi.

Excerpted with permission from Breath Of Gold: Hariprasad Chaurasia, Sathya Saran, Penguin eBury Press, available online and at your nearest bookstore.