Excerpt

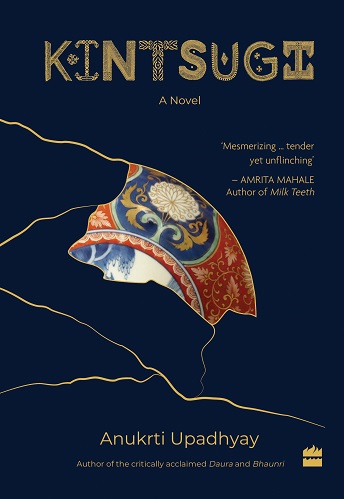

Kintsugi: A Novel

Haruko crouched before a small clay furnace. The furnace was old, the plaster-and-clay chamber under the curved clay tile was filled with the ashes of innumerable firings. She placed the carefully weighed lumps of gold and silver into a crusty, blackened, old clay bowl and slid it into the furnace. She settled back on her heels and flicked the switch on the blowtorch. The hissing drone of the gas-powered torch filled the room as she sent the blue flame flickering into the womb of the furnace, passing and re-passing it over the pieces of metal nestled in the bowl.

‘That’s enough!’ Madanji called out over the trembling sound, even as Haruko switched the torch off. She knew all about the melting points of different materials from her courses in metalwork at the design school. In the six months she had been at Madanji’s gaddi, she had melted metals several times each day. Taking an old pair of iron tongs thickly coated with ashes, she drew the clay bowl out and examined the flame-darkened metals. They were fused together into a sluggish, semi-liquid mass. She set the bowl aside to allow the alloy to cool. Later, she would pull it into sheets or wires as needed on the large lathe which occupied a quarter of the gaddi.

The gaddi where Haruko worked was a set of low-ceilinged rooms in a large three-storeyed haveli built by Madanji’s great-grandfather. The rooms had wooden desks ranged along the walls on three sides, each with a cotton-filled floor seat spread over the thick mattress covering the floor. It was this floor seat of the jewellers and artisans – the gaddi – from which jewellery shops derived their generic name, Madanji had explained to her on her first day. The haveli stood in a narrow street, one among a network of similar streets radiating from the main jewellers’ market, the famous Johri Bazaar. Besides housing the ancestral gaddi, the haveli was also Madanji’s family home. Haruko had been living here too since she had arrived in Jaipur, in a tiny windowless room on the third floor, up steep flights of high, stone steps. The thick-walled room was always cool and opened on to a wide terrace. In the evenings, after the work at the gaddi was over, Haruko spent her time on the terrace, drawing or reading under her solar lamp. All around, as far as she could see, were old havelis, pink and white, slim and tall, stranded like ships.

Besides Madanji, a plump, fair-complexioned man of fifty or so who owned the gaddi, and Haruko, there were three other craftsmen in the room, working silently. Haruko got up, dusted the ashes from her hands and wiped them carefully on her cotton scarf. She slid into the seat near the furnace and drew a lac plate to herself. There were elaborately etched gold pieces affixed to it. These were parts of a gold bracelet she was working on, one of the tasks assigned to her by Madanji. She had engraved a dancing peacock on the bracelet, a traditional motif in the elaborate jewellery craft of Jaipur, but the variations were her own. The peacock had an elongated neck and a curving crest, its train flowed like a Japanese fan. Madanji had approved, conditionally: ‘You can be an excellent chitera, a master engraver, but you want to do everything, be everyone, the ghadiya, the jadiya and the enameller.’ He had shaken his head at the peculiarity of the foreign girl who had come so far to be tutored in the jewellery craft his family had practised for generations.

Haruko picked the long, sharp takua and began the painstaking task of filling brilliant glass enamel into the grooves of the design. It was this traditional enamel work – meenakari – of colours that brightened in fire which had brought her to Jaipur in the first place. She was looking for a suitable project after completing her programme at the design school back in New York. She had spent a semester in Belgium the previous year, completing a gem evaluation certification and had become interested in European enamels. Would she like to explore the Indian enamel? her advisor had asked. It is very interesting, both the technique and the tradition. She had lent Haruko books on the history of enamel work and Indian jewellery craft. The brighter-hued and elaborate Indian enamel, worked in the intricate champlevé style had fascinated Haruko. Her advisor had introduced her to Madanji, a fourth-generation goldsmith, over the phone. I have been to his shop in the bazaar, the professor had told her. You’ll find it all very different from the European jewellery units. The bazaar’s back lanes are a network of tiny manufactories, all ornaments are completely handcrafted. The professor had smiled. It’s your type, I think you will like it.

She did.

The first few days, Madanji had shown Haruko around the narrow alleys of the jewellers’ market in the old walled city. He had introduced her to the master artisans who each practised one particular craft of stone setting or engraving or beadwork, and worked for commissioning jewellers like him. ‘But there are no sunars like my grandfather anymore,’ he had boasted. Nandramji, Madanji’s grandfather, was goldsmith to the kings. Stories of him crafting perfectly fitting bracelets and waistbands for veiled princesses, off measurements taken from their shadows falling on the floor and walls of audience rooms, were part of ornament makers’ lore. When he died, princes had come to condole with the family, and the royal women had sent some of the choicest pieces of their jewellery in memoriam. A few of the necklaces and bracelets were still displayed at the gaddi. Haruko admired the scheme and symmetry of the heavy, elaborate timaniyas and pahunchis, though crafting and wearing them would be difficult now.

Anukrti Upadhyay writes fiction and poetry in both English and Hindi. Japani Sarai, a collection of Hindi short stories and two English novellas, Daura and Bhaunri, have been published to date, and a number of works are in progress. Her short stories have appeared in numerous prestigious literary journals. With post-graduate degrees in Management and Literature and a graduate degree in Law, she also wrote a doctoral thesis on Hindi Literature. She divides her time between Bombay and Singapore.

Excerpted with permission from Kintsugi: A Novel by Anukrti Upadhyay, published by HarperCollins India, available online and at your nearest bookstore.