Travel Through Time And Place With William Dalrymple

Deepika Asthana

March 16, 2018

In the hands of an accomplished historian and travel writer like William Dalrymple, facts of the past become fodder for his travel ruminations. Often, fact can be stranger than fiction; something that is exemplified in his works.

The fortress at Masyaf is a wonderful ruin, straight out of one of the gloomier corners of a Burne-Jones canvas…. Inside it was dark and smelt of dust and bats’ droppings. When our eyes adjusted, we could see stretching out ahead of us long, vaulted corridors buried halfway to the capitals. On either side lay the plain rectangular cells of the fida’i. We picked our way over fallen masonry, and wandered through the castle, silent and respectful, as if in a cathedral. It was a gloomy, eerie place full of sad, empty halls and echoing rubble-filled cisterns. Preserved by centuries of warm and Mediterranean weather, it seemed only newly deserted and so doubly melancholy.

It is exactly this kind of delicate interplay between the past and the present that has endeared William Dalrymple to readers across the globe. In In Xanadu, his description of the city of Masyaf in Northwestern Syria and his visit to the Masyaf castle, at once evoke images of the fida’i of the 13th Century and the unfortunate ruins that subsequent plunder and war created. A Dalrymple book allows the reader to seamlessly glide through both time and space, creating a unique multi-dimensional experience. The author makes the past come alive in the present, thereby making it more tangible. He makes it almost real.

After the stone-throwing had been going on for two hours, the police suddenly intervened. They escorted the mob away, then returned and collected all our weapons: they took all our lathis and kirpans; they even took away the stones and bricks that were lying around our houses. They said: “There is a curfew. Lock yourselves up”. When we had followed their instructions and retreated inside our houses, they let the mob loose.

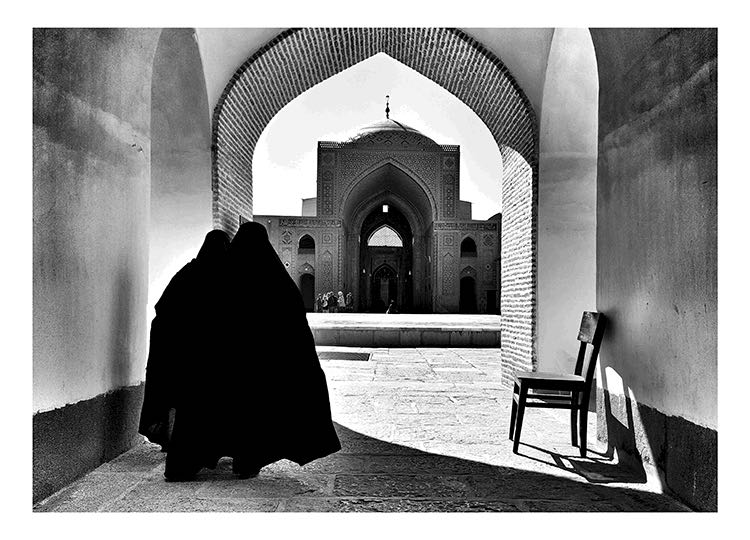

(Untitled Photo by William Dalrymple via Vadehra Art Gallery)

“One day in late October, Olivia and I stumbled upon Ali Manzil, the home of Begum Hamida Sulta. Still, it was one of the last havelis still occupied in the old style. A narrow passageway led from the gatehouse into a shady courtyard planted with neem and mulberries; the open space flanked by a pair of wooden balconies latticed as intricately as lace ruff….Yet even here, the inevitable decay had set in. The outer courtyard had recently been destroyed and its space is given over for shops. The balconies were collapsing; the paint was flaking. The veranda lay unswept.”

Bureaucracy is a unique animal that transcends both cultural as well as geographical boundaries. It is all-pervasive and is known to thrive in all sorts of environments. No book on travel is complete without a nod to this ubiquitous animal.

“Officer (suddenly severe): When you arrived in our India, I am thinking you brought in one computer, one printer, one-spiece cassette recorder and one Swan electric kettle

WD: That’s very clever of you. Oh, I? see (the truth dawns). Your colleagues wrote them in the back of my passport when I arrived.

Officer: Sahib, I do not understand. You are planning to leave our India but I am not seeing one computer, one printer (reads out list from passport).

WD (nervous now): No – but I’m not going for long. I won’t be needing the kettle. I’m going to be staying in a hotel. Ha! Ha!

Officer: Ha! Ha! But Sahib. You cannot leave India without your computer and other assorted imports.

WD: Why not?

Officer: This is regulation

WD: But, this is absurd

Officer (wobbling head): Yes, sahib. This is regulation

WD: But I’m only going for five days

Officer: This has no relevance, sahib. One day, one year, it is same thing only.”

The seasoned traveller will at once find humour in the above situation. However, for the novice traveller, situations like the one above can be unnerving and can entirely put them off travel.

(Untitled Photo by William Dalrymple via Vadehra Art Gallery)

“‘What sort of crimes? I thought Lahore was a stable city, very prosperous and clean.’

‘No no,’ he said, his face lighting up. ‘it’s full of crime: murder, robbery, rape. Especially rape. There is more rape in Lahore than any other city in Pakistan.’

‘Really?’

‘Oh, yes. Last week in my street a fourteen-year-old girl was raped. She was a pretty girl. Educated. Would have been very beautiful. But her face is now badly scratched; she will find it hard to get a husband.’

‘How horrid. I always thought rape was a Western disease.’

‘Oh it is. But we’re very westernized in Pakistan.’”

To understand the past and appreciate the present is indeed a gift. To be able to view the world around us through a lens of knowledge and mirth, a blessing.

Writer, investor, crypto enthusiast, nomad, mother of twins and founder of ARNA Write Strategy (a content writing agency). Deepika is a heady mix of all of that and more.

Read her articles here.