Feature

What Women Want: ‘Topics Of Conversation’ On Love And Desire

For as long as we have proudly (and sometimes not so proudly) been reading books that talk about love and relationships, we have mostly been subjected to a simplistic view of a woman’s love and desire. A woman desires a man, they fall in love, have misunderstandings, separate, meet again, and have their HEA. In the process, the depth of a woman’s desire largely goes unnoticed.

Even today, the topic of a woman’s desire and her thoughts on sex are still considered taboo – to the point of there being very little conversation on the subject. Case in point, Ismat Chughtai’s Lihaaf. Chughtai was tried because her books hinted at lesbianism, and depicted sex, which was considered a taboo topic. Chughtai had to defend herself and her book in court.

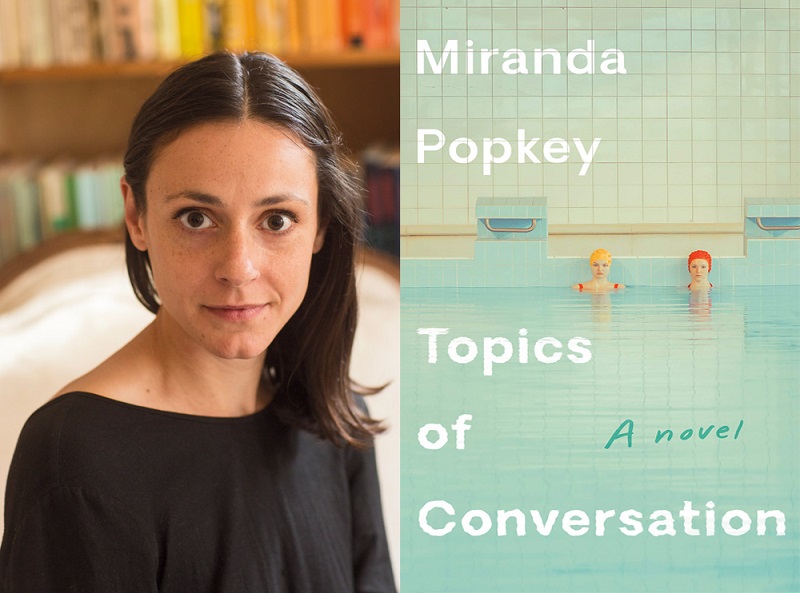

But today, authors are choosing to brave this taboo to give conversations around sex, desire and love from a woman’s perspective the space they deserve. Books like Miranda Popkey’s Topics Of Conversation are portraying the ‘other’ side of desire that has been shamed by society for too long. Liberalism and feminist movements have helped provide female authors with the space to experiment with female desire and its various shades. Popkey, in her book, shows us how love and desire are complex emotions, and how women ought to be free to experience this fully.

What Women Desire

Topics Of Conversation revolves around the stories of the women the narrator meets, her friends, and even anecdotes from her life, and is spread over the course of 17 years. In one story, the narrator, who is now a mother, is regaling the tale that changed her life. She tells the other single mothers the story of an older college professor with whom she spends a night. He presses her down on the bed, with a strict order to not move. He watches her, fully clothed, and they do not have sex. The narrator is thrilled to discover that she likes to relinquish control – something she might have never realised had the professor not shown her. This is followed by another story where the narrator, who is now married to a man, finds herself in a room with a stranger. She tells the stranger she wants to be dominated, and that she hates making choices.

Is this form of desire okay? What if a woman’s wants don’t always conform to what society dictates? What if women want ‘bad’ things – bad, because they have been deemed demeaning, or perverse?

Popkey’s narrator feels free to articulate her desire, even though her manner of articulation shows us the contradictions of the human mind over her thoughts. She always weighs her desires and what is appropriate in her mind, takes social and moral conventions into consideration, and there is always a ‘churning’ going on in her mind. Ultimately, her desire to not make a choice means she is choosing to hand over the reins to someone else. Many women would find this diminishing since they believe that having a man ordering them in the bedroom goes against their feminist principles. But, by giving up control, the narrator is reclaiming it since she removes the expectations and disappointments that come with responsibility. Just as the wrong choice can end up suffocating us, the right choice (in certain cases) of submission can also be seen as a form of freedom.

(Image via ABC Life)

Feminism And Desire

During the 1980s, radical feminists claimed that ‘heterosexual sex under patriarchy inevitably normalizes male violence and reinforces female inequality; women should, on account of this, consider repudiating their desires’. But sex-positive feminists argued that denying women their choice of pleasurable sex is also abhorrent, and if a woman consents to it, it should be acceptable. Otherwise, feminism would end up doing what the movement frowned upon – slut-shaming and stopping women from having what they want.

The narrator in Topics Of Conversation doesn’t reach the conclusion of what she desires in an instant; instead, her mind resorts to ‘churning’- weighing facts and fantasies, considering what she wants vs what society deems appropriate. In one of the stories, the narrator debates with herself on how the ideas of ‘sexual hierarchy’ have been woven into our behaviour by society, with set expectations from either gender about how they can proclaim their desires – ‘a certain cultural consensus about what women wanted and how men should go about giving it to them’. We only know what has been taught to us, and what we have been conditioned to think as appropriate or shameful. It’s crucial that we understand that every person has unique desires and that they are entitled to their choices.

In one of the first stories, Artemisia, a 40-something woman explains how she left her first husband after they had violent sex; not because she was frightened by his sudden rage, but because he showed her how he was tied to the whims of jealousy, and in turn, looked weak in Artemisia’s eyes. His desperation to seek power over her was what led him to be violent towards Artemisia, but she saw what it was, the weak will of a man wanting to grasp at power using his body. What Artemisia wanted, and perhaps many of us want, is brilliantly articulated when she says that she needed ‘a strong man who could take care of her without needing to control her’.

What links the stories in Topics Of Conversation is desire – what women desire, how they express it, and how they sometimes hide it. The most shameful thing in the novel is not what women desire; rather, it is summed up in one sentence: ‘When [women] thought about sex we thought mostly about ways to defend against what we didn’t want instead of ways to pursue what we did. So that now the way I thought to attract a man was to make myself vulnerable to attack.’

Popkey gives a voice to women’s desires, and, in turn, shows us that it doesn’t make us any less of a woman if we give in to them. The women in her book do not conform to society’s views of being unmatched in virtue. Instead, they seek love and desire people, even when it’s not considered healthy. But that is how desire operates, isn’t it? It doesn’t heed logic or sense, and it’s time women allowed themselves to let their desires manifest the way they want.

(Image via The Nerd Daily)

Love As A Choice

While the stories in Topics Of Conversation revolve around affairs, submissiveness, self-sabotage, etc., the most noticeable themes are the need to be simply cared for, and to be free of responsibility and expectations in love. The women, instead of losing themselves in a ‘love’ that threatens to take over their individual selves, decide to break free from what they feel is a ‘toxic’ love for them.

The narrator of the novel meets a nice guy, decides that her life ‘was going to be suburban, it was going to be upper-middle-class’, but eventually divorces him, even though he loved her. She does this despite knowing that he’s ‘so kind and so supportive and emotionally generous and a good listener…everything a liberated woman is supposed to want’. A man like this is every feminist woman’s dream, but what happens when the woman cannot love him despite his admirable qualities? Her remorse finds its roots in feminism – how can a liberal woman do that?

Her story puts forth an important question – why are women supposed to feel guilty when they don’t love the person they are supposed to ‘love’? While earlier it was society that dictated who a woman should love, today it is the feminist movement that talks about the need for women to love a kind and caring man. Unfortunately, love rarely works that way. The narrator does regret having to hurt her husband, but isn’t loving the person she desires part of what freedom is all about?

What ties these women together is love, but beyond that, the need to love whomever they choose. It might not always be the best choice and they might get hurt along the way, but this freedom to choose and experiment in love is what sets these women (and book) apart from Harlequin romances, and most chick-lit novels. There is no enemies-to-lovers trope, no boy pulling the girl’s pigtails to show his love. This is a woman’s world, and she wants to love on her own terms.

(Image via The New Yorker)

It is heartening to see female characters choosing to work towards what they desire, and authors experimenting with the full spectrum of human desire and relationships. It is empowering to see women creating their own arcs, being in charge of their own lives, even if they are messed up and imperfect, and navigating love and desire on their own terms.

It is truly admirable of Popkey to tell the world to stop idolising and showing women as goddesses of chastity and purity. After all, women have their own desires and ideas of love that may not always bend to the norms of society.

It’s time women break free.

Prasanna is a human (probably) who makes stuff up for a living. When she’s not sleeping or eating, you’ll find her in the quietest corner of the library, devouring yet another hardbound book. She vastly prefers the imaginary world to the real one, but grudgingly emerges from her writing cave on occasion. If you do see her, it’s best not to approach her before she’s had her coffee.

She writes at The Curious Reader. You can read her articles here.