Sabrina And The Rise Of The Graphic Novel

Deya Bhattacharya

August 20, 2018

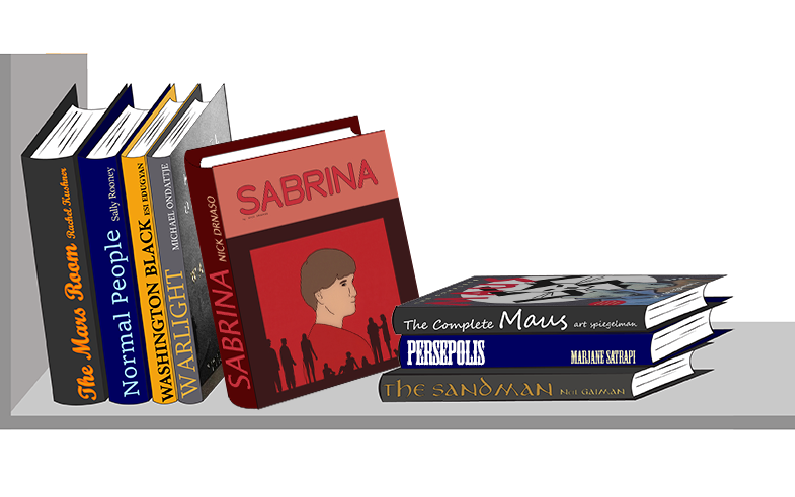

Sabrina – The Plot and the Character

Sabrina is set in the Chicago area, where Drnaso is from. Right in the beginning, we meet Sabrina, the character around whom the story revolves. She is a homely young woman who is cat-sitting for her parents, when her sister, Sandra arrives. They briefly reminisce about their parents, talk about Sabrina’s boyfriend and do the crossword together. Sandra recounts to Sabrina about a bus trip she took by herself when she was 19, and how it had opened her up to the dangers of the world. Both of them plan a bicycle vacation along Lake Michigan for later that year.

Sabrina is enthusiastic about the said plan – “That sounds great. Get out of the city. Get away from the internet.” – and she leaves. This is a devastating break because little did we know that this is the last time that Sandra, and the reader, will ever see her. With this, we find ourselves reluctantly enmeshed in the lives of Sandra and Teddy, Sabrina’s boyfriend, and Calvin Wrobel, a friend of Teddy’s who works a desk job at the Colorado air force base. But this is not what we signed up for – we wanted Sabrina, and Drnaso knows this along all. Instead, we find ourselves in the throes of a crime that fuels the public appetite for personal tragedy, the systems that incite media’s predisposition with misinformation, and the ubiquitous devastation of isolation in our times.

Drnaso’s illustrated work is stark and unsettling, and it’s all a part of a well thought out strategy to both calm and disrupt the reader at the same time. Sabrina’s panels are scientifically illustrated – minimalist, undramatic and pastel – and build an atmosphere of doom throughout the story. Drnaso’s characters are minimally sketched, emotionally sparse and non-manipulative. The characters do not give into sensationalism, and primal emotions of grief and outrage are understood through deafening silences and pauses in the panels, and the unending stupour and feeble catatonia of the characters. Sabrina’s lattice of panels with its dispassionate, detached main characters makes its readers uncomfortable. Described as “the story of what happens when an intimate ‘everyday’ tragedy collides with the appetites of the 24-hour news cycle”, the graphic novel is astonishingly relevant to our present life.

(Image Credit: Drawn & Quarterly)

But I could not put down Nick Drnaso’s work without first completing it, and then, I dove in again – I reread it, only to feel discomfited again. Drnaso’s visual style in Sabrina is so subversive, so insurrectionary that it hooks its readers in, despite the ubiquity of an effervescing discomfort. Drnaso’s masterpiece feels like a deep exercise in loneliness.

The book has already amassed immense praise. Drawn & Quarterly reports Zadie Smith’s comments on Drnaso’s work – ‘I have read about our current moment. [B]eautifully written and drawn, possessing all the political power of polemic and yet simultaneously all the delicacy of truly great art.’ Novelist Adrian Tomine calls it ‘incisive, chilling, and completely unpredictable’. And Drnaso’s work is worthy of all the acclaim; it is significant in the ways that it has essentially distorted the long-standing distinction between novels and graphic novels. It has moved us into an uncomfortable literary space, where we want to appreciate the ways in which graphic novels speak to us, yet we don’t feel amenable about its inclusion within the literary fiction categories.

(Image Credit: It’s Nice That)

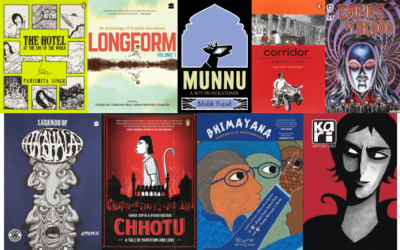

Sabrina Blurs the Distinction Between “Traditional” Literary Formats

What is it that shocks the readers about Sabrina the most? It is not just the blood-curdling familiarity of the paranoia of our lived realities and the unpredictability of how we live our lives; but Sabrina unsettles us because, with its appearance on the Man Booker longlist, there is also a literary paranoia that one faces in these times.

As Drnaso weaves a mind-blowing narrative of the intricacies of personal tragedy and conspiracy theories, he also dismantles the extant structure of the literary world. He befuddles the average reader because his work reads like a novel, the emotion he evokes through his work are those, often associated with novels, but Sabrina is not the idealistic novel; it is not one that is expected to be on a prestigious list like the Man Booker. Essentially what Drnaso does is use the medium of a graphic novel to make a perspicuous enquiry into the human condition – a responsibility that graphic novels are particularly not permitted to take up.

In fact, a few readers were so unnerved by Nick Drnaso’s Man Booker mention that author Joanne Harris had to put out a list myth-busting tweets on graphic novels under the hashtag #TenThingsAboutGraphicNovels, where she states that graphic novels are novels and that they intersect and exist in all genres. She also wrote about how we perceive graphic novels: they are not lesser literature, and the images do not ‘diminish the text, or the themes, or the complexity of the story’. Her analysis is very relevant, at this point, because it informs us of the role of graphic novels in an era where reading habits and attention spans are continuously being challenged by various kinds of content. She calls out the literary family – “don’t be that guy”, she says, and she is right!

(Image Credit: It’s Nice That)

It cannot be denied that at this point, Sabrina, though a graphic novel, sits at the intersection of the ideal, traditional novel and the graphic novel. The Man Booker longlist has unwittingly changed the paradigm of what an ideal book might look like. Sabrina has swooped in and pointed out the hypocrisy of the literary world. And in this, it contributes greatly to the rise of the modern graphic novel.

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.

‘Sabrina’ raises pertinent questions about the times that we live in and forces us to reflect on them. It does not really have the contrivance of a formal plot structure. It feels rather like an account of what might unfold if this were to happen in real life. Yet, there is palpable tension in the novel.