Feature

Why You Should Read Literature From Around The World

Devanshi Jain

June 20, 2019

Many readers tend to only read what they are comfortable with. We stick to books from familiar genres, written by authors we’ve read and enjoyed in the past. Often, these books tend to also be set in the same locales. After all, authors usually write what they know about and not all of them have the time or money to actually visit the places they would like to write about.

However, this poses a problem because it is very likely that most of what we read is set in the U.S., U.K. or India. Our exposure to different cultures and countries is limited as a result. It doesn’t help that most of the television is also produced in these countries. While this has led us to become extremely familiar with the streets of New York, the pubs of London, or the underworld of Mumbai, we know next to nothing about countries like Ukraine or Algeria.

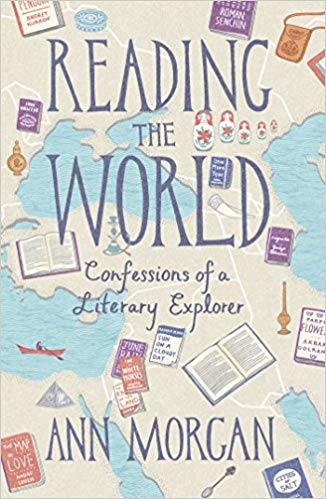

Ann Morgan had a similar realisation. When she looked at her bookshelf, she realised that most of the books there were written by British and North American authors. Calling herself a ‘literary xenophobe’, she decided to spend 2012 reading one book from every country in the world. In Reading The World: Confessions Of A Literary Explorer, Morgan discusses her experience and how it changed the way she viewed the world. Instead of going into the details of each book, and her impressions of them, she uses her learnings as a jumping off point to discuss issues like nationality and the problems with publishing.

Why We End Up Reading The Same Kind Of Books

In Reading The World, Morgan highlights some of the reasons why our reading has become increasingly insular. We now live in the age of the Internet where algorithms tell us what we should read based on what we have read. You may have noticed that every time you buy a book from Amazon, or even search for one, you see recommendations based on what those who have bought the same book as you have looked at. We see what our friends are reading. We read what Bill Gates is reading and what Oprah recommends. We pick up books that our favourite authors recommend and endorse. After all, chances are, if an author we admire likes a book, we are going to like it, too. As Morgan writes, publishers and retailers have worked to “ensure that we are never more than a few clicks away from a book that is like a book we like.”

We are told to read more of what we like. And why not? It’s so much easier to stick to what we know than to get out of our comfort zone. With familiarity as a yardstick for what we read, it is easy to understand why there is a lack of availability of translated versions of foreign language literature. After all, why should publishers bother to discover literature written in languages they are not familiar with, go through the process of acquiring rights, find someone to translate it, and then convince readers to buy a book set in a country they may never have heard of or care to learn about? It’s so much easier for them to just stick to what they understand and are confident that readers will buy.

While it is easy to blame the Internet (and ‘big publishing’) for our narrow reading habits, it is up to us to ensure that we make the virtual world work for us instead of against us. Just because we don’t know enough about the literature of a particular nation, it does not mean that we can’t find out. Morgan took to the Internet to find recommendations for books she should read, and was surprised by the generosity of people. For example, a woman actually sent her a Malaysian book (and one as her ‘Singapore book’) all the way from Malaysia to London. Others engaged with her repeatedly to help her pick what to read; some even spent hours researching. A team of volunteers translated a book of short stories for her. A few authors gave her previously unpublished translations of their work just so she could complete her challenge. Another wrote a custom short story just so she could have something to read from South Sudan. And all because she harnessed the power of the Internet.

Let’s face it, the real reason we don’t read literature from different countries is that we don’t want to. Why bother reading translations when we can just read works written in English? Why struggle to understand cultures we have never heard of, or colloquialisms and idioms we have never encountered before? Why not simply limit ourselves to what we know?

Why You Should Read Books From Different Countries

The world is getting increasingly globalised, and therefore, it has become even more important for us to try and understand it. Unless you’re Chris Guillebeau, you probably haven’t been to every country in the world. Chances are, you don’t even know the names of all the countries, or even how many there are. Fun fact: the number is debatable. While Morgan decided to go with the countries identified by the U.N, she did so only after much deliberation.

In lieu of visiting these countries, your next best option is to read literature that comes out of there. Not only will this give you an opportunity to travel to these countries through literature, but you will also become a better citizen of the world. You will learn about the culture of different countries, which is key to truly understanding what it means to live in today’s interconnected world.

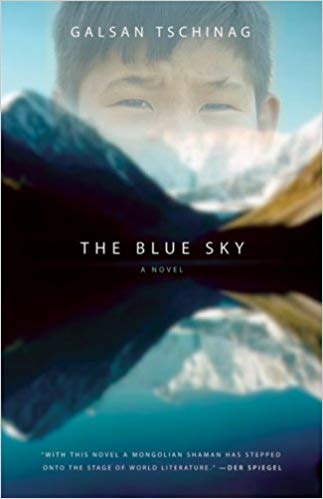

Morgan believes that we should read a novel for discovery. She says, “Rightly or wrongly, we tend to regard literary works as windows on other worlds.” She is absolutely correct. Literature gives us a glimpse into worlds we know nothing about. Through books, we can peek at the dreams of a shepherd boy in Mongolia (The Blue Sky by Galsan Tschinag, Mongolia), or understand the struggles of a Rwandan woman as she tries to survive in a nation affected by genocide (Teta by Barassa, Rwanda).

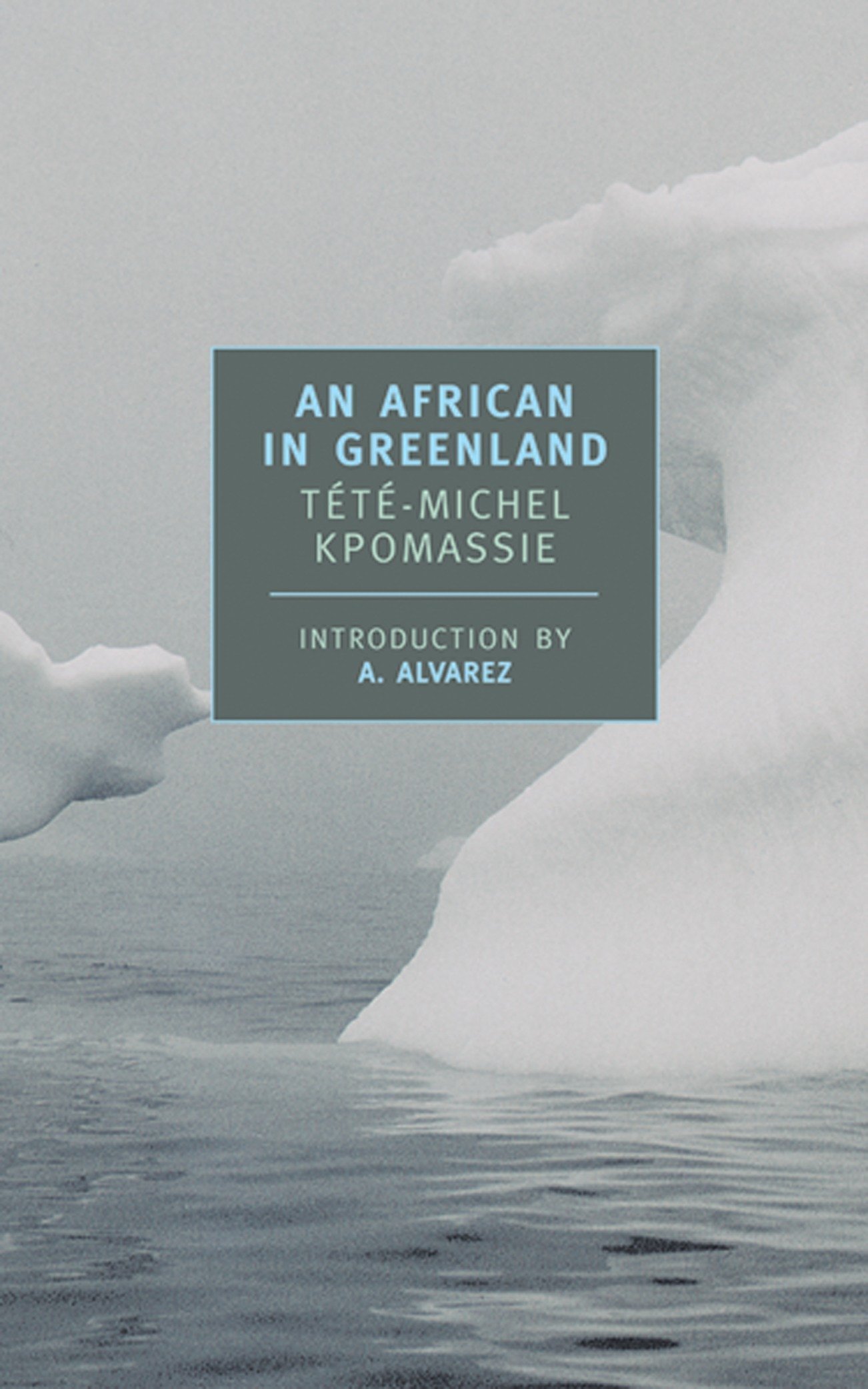

We can learn about the customs of a tribe in Togo (An African In Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Togo) or what happens when cultures collide (The Sexual Life Of An Islamist In Paris by Leïla Marouane, Algeria). We can find out how the discovery of oil changed a small Arab town (Cities Of Salt by Abdelrahman Munif, Jordan) or how indigenous tribes in an Ecuadorian jungle were exploited and oppressed in a feudal society (The Villagers by Jorge Icaza, Educador).

We can explore different cultures by reading about life in Tuvalu (Tuvalu: A History by Various, Tuvalu) , the Tu’i Tonga Empire (A Providence Of War by Joshua Taumoefolau, Tonga), the Maori culture (Once Were Warriors by Alan Duff, New Zealand), or Kuwaiti high society (The Chronicles Of Dathra, A Dowdy Girl From Kuwait by Danderma, Kuwait).

Perhaps, you might choose to read some children’s literature from Dominica (The Snake King Of The Kalinago by Atkinson School, Dominica) or read one written from a child’s point of view (Why The Child Is Cooking In The Polenta by Aglaja Veteranyi, Switzerland).

Chances are you’ve not even heard of some of the countries mentioned here, forget about knowing about what it is like to live out there. Literature can teach you about the daily lives and trials and triumphs of millions of people around the world. It is books that will help you empathise with and understand the actions of those you didn’t know existed. It is reading that will help you realise that, at the end of day, we are all human and it doesn’t matter where we live, which God we believe in, or who we love.

How To Go About It

While I laud Morgan’s quest and admire her for actually reading 197 books over the course of a year while juggling a full-time job, let’s face it, it is extremely difficult. So, instead, why not take it slow?

- Set yourself a simple goal like reading 15 books from different countries.

- Begin by making a list of the countries from which you’ve read books and identify the gaps. For example, have you never read a book from a country in South Asia or Africa? Have you completely ignored Australia?

- Next, identify 10-15 countries that fascinate you. Perhaps, you have always wanted to take a trip there or maybe they have been in the news recently. Keep in mind the gaps you identified in Step 2.

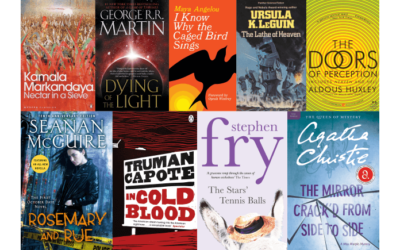

- Now pick 1-3 books that represent each country on your list. They can be set in that country or be written by a local author. You could also pick books that reflect the culture of that country. To get started, take a look at Morgan’s list, where she identifies at least one book from each country. In many cases, you’ll find several recommendations.

- Visit your local bookstore or search online for these books. Interestingly, I searched for all 197 books she read during her challenge and found that around three-quarters of them are available online. While some may be expensive, many are affordable.

- Start reading.

Instead of limiting yourself to what you know, it is time to expand your horizons and go on a journey of discovery. Not only will you be well-read but you will also be more aware of the world you live in and, dare I say, become a better person. Take it slow if you need to, but commit to reading more literature from around the world. You won’t regret it.

Devanshi has been reading ever since she can remember. What started off as an obsession with Enid Blyton, slowly morphed into a love for mystery and fantasy. Even her choice of career as a lawyer was heavily influenced by the works of Erle Stanley Gardner and John Grisham. After quitting law, and while backpacking around India, she read books on entrepreneurship, taught herself web design and delved into social media marketing. She doesn’t go anywhere without a book.

She is the founding editor of The Curious Reader. Read her articles here.

A wonderful post although I’d disagree with your sentence beginning “let’s face it” which suggests readers don’t read internationally because they don’t want to. I think some of the reason also falls onto publishers and bookstores in the English language world because there are so few translations and they aren’t the books on the first table as you walk in the door of a bookstore. I live in France and so many of my adult students read books from different countries, I remember asking one who is that author, he said, he’s a Colombian author, I asked where he found it, he said in the front table of the bookstore. In France 45% of the fiction they read is translated from other languages, so they don’t rest have to even desire to read diversely, they are being offered it automatically. We have to have itrsised in our awareness and then hunt for it, because as you rightly point out, everything around us is conditioning us towards the familiar.