Feature

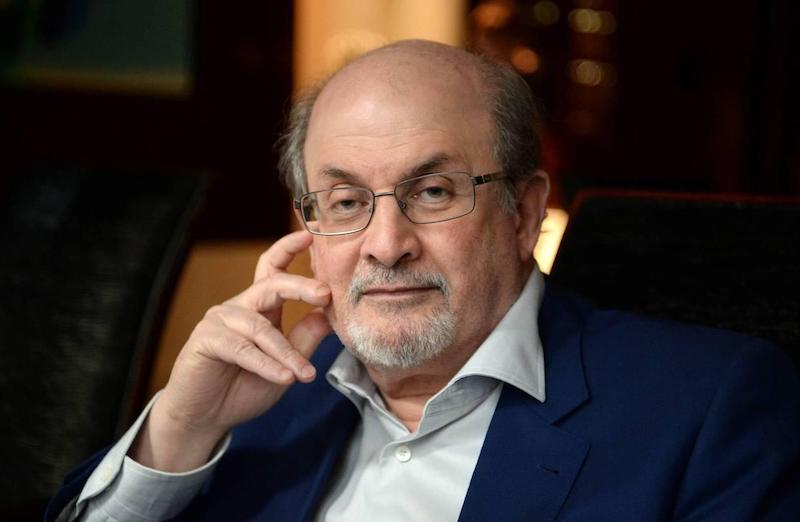

Fiction Within Fiction: Interpreting Salman Rushdie’s Quichotte

A new book by Salman Rushdie invariably demands the collective attention of the entire literary community. As Cervantes mentions in his magnum opus Don Quixote, the greater the fame of the writer, the more closely are his books scrutinised.

Shortlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize for Fiction, Rushdie’s Quichotte is a roar of narratives that encompasses everything of everything – fantastical real life, commonplace magic, the endless multiplicity of today’s world – and is self-conscious about it.

Self-Conscious Fiction And Quixote

Fiction is a narrative consisting of imaginary people, events, and descriptions presented as reality. Metafiction – literally, beyond-fiction – presents fiction as fiction; it is a narrative of a narrative, a story within a story, that questions the nature, method, and presumptions of fiction, and thus of reality itself. It draws attention to the fact that the story, characters, and sometimes the author themselves, may or may not be fictitious. The narrative voice often steps out of their narration to remind the reader that they are reading a book, and sometimes, may even don the role of a character and enter the story to prove a point.

In Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605) – one of the earliest and most seminal examples of metafiction – the narrator explicitly tells the reader that the text of Don Quixote was originally written by an Arab historiographer, translated into Spanish by an anonymous Moor, and finally edited by Cervantes. He implies that Don Quixote is a real historical figure, but also states later on in the story that Arabs are addicted to lying – so is Don Quixote a real or fictitious character? And if he is fictitious, who is his real author?

Metafiction is an author-centred mode of writing. Everything – narrator, character, story, voice – comes down to the author – real, implied, or otherwise. Like Cervantes, Rushdie too raises questions about authorship in his book – he pays homage to Cervantes, by inventing an author who is himself inspired by Cervantes.

This character, called Sam DuChamp aka Brother, is the author of the book within the book that is Rushdie’s Quichotte. He talks about his new project, which also happens to describe Rushdie’s latest endeavour:

‘He talked about wanting to take on the destructive, mind-numbing junk culture of his time just as Cervantes had gone to war with the junk culture of his own age. He said he was trying also to write about impossible, obsessional love, father-son relationships, sibling quarrels and, yes, unforgivable things; about Indian immigrants, racism toward them, crooks among them; about cyber-spies, science fiction, the intertwining of fictional and ‘real’ realities, the death of the author, the end of the world.’

It’s So Meta

Rushdie’s novel is like him: ambitious, smart – sometimes over-smart – critical and undoubtedly brilliant. Looking at it simply, Quichotte is a satire. A satire about modern America, Britain, and India, about the consumption of media, and the intolerance in a democracy, about love and about family.

On another level, Quichotte is a picaresque tale about a person called Quichotte, framed within the narrative of the author writing it – framed within the outer text which encompasses both these stories. It is metafictional in that it is not just a story within a story but is a story that admits its own artifice. The book not only has characters that know they are being written about, but characters that have opinions on the writing.The book is metafiction squared, metafiction within metafiction, where the story is so layered that characters made up by characters made up by characters not only question their own existence, but also question their maker’s existence. They are self-reflexive, self-critical, self-conscious, and are constantly reminding the reader about their fictionality.

Yes, it’s so meta; enough to drive you nuts, enough to make you want to chuck the whole thing. But you read on, precisely because it’s so meta.

Quichotte’s Story – And The Story Behind It

The inner narrative of Rushdie’s novel is that of an old man who calls himself Quichotte and his quest to win over the love of a TV celebrity called Salma R. It is ‘The Age of Anything-Can-Happen’, and Quichotte conjures a son into being and names him Sancho; the two of them journey across America, gradually figuring out that the given of the world is no longer a given.

Just as 15th century Quixote is driven mad by reading too many romance novels, the modern Quichotte suffers from a ‘peculiar form of brain damage’ caused by watching too much TV. Like Quixote, he self-consciously decides to become the author of his own life and builds himself a new identity by choosing a knightly pseudonym for himself. The character of Quichotte is based on the recording of the French opera Don Quichotte, which itself is loosely based on Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

Just as Quixote builds his own story by picking and naming characters to suit his chivalric quest, Quichotte identifies members from his memory, family, and imagination to star in his own adventure.

Except, this family, these memories, are not his alone but also those of the author writing his story. Like his main character, Brother is also an Indian immigrant operating under a pseudonym, also in the twilight of his years, weighed down by a dysfunctional family history. The two stories reflect one another. Quichotte to Brother is a shadow self, and his story is a metamorphosed version of his own, revealing itself in the mirror to him every day. Brother becomes unsure whether life is imitating art or art is imitating life. ‘Deafened by the echo between the fiction which he had made and the fiction in which he had been made to live,’ his family and life blur together with Quichotte’s in his head. “Now Quichotte and I are no longer two different things … I am a part of him, just as he is a part of me,” he says.

(Don Quichotte Opera Image via The Scene Into)

The Third Eye

In an interview, Rushdie states, “I wanted my book to have a parallel storyline about my characters’ creator and his life, and then slowly to show how the two stories, the two narrative lines, become one.”

Rushdie, since the beginning, has been present within the narrative, wielding his authorial intent by stitching together the entire narrative. He deliberately echoes facts from Brother’s life in his fictional tale, duplicates themes and characters within it, and presents the stories of Brother and Quichotte in alternating chapters to create the effect of disorientation in the reader’s mind. Acting as the omniscient god-like narrator, he uses a uniform fairy-tale tone in both layers, unfolding the holistic story in a traditional linear manner, while making use of footnotes in Quichotte’s chapters as well as Brother’s to fill us in on minute details. He breaks the fourth wall in multiple ways, addressing us as ‘kind reader’ and including us in the narrative, discussing with us the status of the book as fiction. By immersing the reader into the story, there is no one left to interpret it. With the reader entrenched within the text, the unreliable author-/narrator becomes the means and the end of the story.

But does he really?

Sancho – a triply removed fictional character – who describes himself as ‘a teenage son of a 70-year-old born just the other day’, reflects on the matter of authorial creation. He can not only see into the mind of Quichotte – his creator – and his memories, but can also sense a third person, a phantom, beyond his ‘dad’. He suspects that just as Quichotte invented him, somebody else invented Quichotte.

By this line of thinking, it is possible to assume that just as the author/narrator Rushdie invented the author who invented Quichotte who invented Sancho, somebody else invented Rushdie. The power over the characters’ destiny and the plot of the larger story seems always to be one step deferred, never fully in the hands of a single authorial entity.

(Salman Rushdie Image via WAMC)

Stranger Than Fiction

A book of fiction is based on an agreement between the writer and the reader about the natural laws of its world. Metafiction is based on its disagreement; there are no natural laws in the world of such a book. The point of metafiction is to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality, author, narrator, and character, reader and text. The world of Quichotte is glitchy, fast and noisy. Reality is in a flux and every wall is permeable – literally too, as the reader finds on the last page. No one is in charge, creators are created, and authors seem to write themselves into their own texts.

—-

There is not much place for what the reader thinks in such a book; our reading of the text is as valid as the enquiries of the existential identity of fictional characters. A book like Quichotte interprets itself, and the reader is, somewhere, thankful for it.

Aashmika is a writer from Mumbai. She recently completed her MA in Creative Writing from Oxford Brookes University and also has an MA in English Literature from Mithibai College, Mumbai. She is also a belly dancer, which successfully battles her professional introversion. When she isn’t reading or writing prose or poetry, she is watching TV shows. She loves animals, tattoos, nature, and taking pictures of things.

Aashmika is currently working on her first novel (but don’t ask her about it).

Read her articles here.

Brilliant! Love Rushdie’s acerbic wit and experimental style but it can be too much to digest and make sense of. Just the kind of analysis I needed to augment my reading with.

Thanks, Mose! We’re glad you enjoyed it 🙂