Feature

Contemporary Naga Writings’ Reclamation Of Culture And History Through Orality

Khaled Hosseini, in an interview he had done in December 2010, said:

“Too often, stories of Afghanistan centre around the various wars, the opium trade, the war on terrorism. Precious little is said about the Afghan people themselves- their culture, their traditions, how they lived in their country, and how they managed abroad as exiles. I hope my books give readers some insight into and a sense of the identity of Afghan people that they may not get from mainstream news media. Fiction[Writing] is a powerful medium to convey such things.”[1]

I was so moved when I read his interview. And I thought isn’t that us? This is the beautiful thing about writing- you feel, you connect, you empathise, you humanise, as one. For many decades, rather centuries, Nagas have been written about or spoken about/for by others as the ‘other’ and it is only in the latter half of the last century that they have begun to actively write and speak for themselves. The many Nagas who are writing these days, all, albeit in different ways, share ‘exactly’ what Hosseini felt when he chose to write. As Chimamanda Adichie often repeats, “Show a people as one thing, only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.[2]” There is a danger in linear narratives.

[1] Hosseini, Khalid(December 2010). Afghan News. Embassy of Afghanistan in Japan. p5.

[2] Adichie, Chimamanda(2009). The Single Story. TED talk.

The Need To Write

Writing is a powerful response to the common problem of stereotyping that is suffered by many, but very acutely by those who belong to the minority cultures. There are multiple versions to the same story and the more people write, the more the world sees these many sides and that makes for fairer understanding. Khaled Hosseini chose to write because he wanted people to see the many Afghanistans outside the stereotype created in the mainstream global gaze, that the Afghanistan we think we know is just the tip of the iceberg or perhaps that the Afghanistan that we see is a deliberate creation.

Likewise for the contemporary Naga writer/poet, besides the creative urge to write and express, there is an overpowering urgency and need to write so that people understand them for who they are and not for how they have been mis/branded. They also write to respond to past representations/misrepresentations and to tell their side of the story, to rewrite history or to offer recourse to written/established history. In addition, they write to reclaim dignity and assert identity and, most importantly, inscribe it to written posterity.

Thus Naga writing in English, though a more recent phenomenon, is undoubtedly a movement on the rise; it is here to stay, dynamic and inspiring. It has garnered wide readership thanks to the likes of Temsula Ao, Easterine Kire, Monalisa Changkija, Nini Lungalung, Abraham Lotha, Visier Sanyu, T. Keditsu, Renthunglo Shitiri, and many more.

(Image of Lotha Naga Warriors. Photo credit: Shanthungo Ezung)

The Evolution Of Naga Literature

Naga written literature is in its developing stage, spanning just a few decades and to understand the literary tradition of the Nagas, one has to firstly interact with their oral tradition as it is the first and only primary source of their original literature; secondly, one cannot talk about the literary present without the literary silences and breaks in between. As Tilottima Mishra put it, “The scribal tradition is a recent one amongst the Nagas and before the development of a script for the Naga languages through the efforts of the American Baptist missionaries, literature was confined only to the oral form.[3]”

Now, the oral tradition of the Nagas was a community-centred tradition which put the community before the individual. That is also presumably one of the reasons why, more often than not, Naga folktales have many nameless characters.

After the arrival of visitors/outsiders to Nagaland, “oral literature was silenced”[4], the repercussions of which are seen till today. Once they left, what was left of the Naga culture was an unrecognisable image of its formal self. Centuries-old traditions disappeared. People were confused and embarrassed at once of their old ways- language, literature, customs, and beliefs.

Easterine Kire talks about this gap and the “silencing of oral narratives at critical periods in their history” and the different phases of silencing in her Gopinath Mahanty Lecture of 2016. According to her, the first phase started with the coming of the American missionaries around the 1860s where tradition was traded for civilization and the Nagas saw what was theirs with doubt and scepticism. The second phase came in around 1919 after the British occupation and World War II/Battle of Kohima when people were busy rebuilding their ravaged homes and houses after the war. The third began after Indian Independence in the 1950s when the newly educated Nagas, aware of their political rights, got so busy writing letters to the Government of India, that their own narratives went silent[5].

In this tragic melee, much of Naga lives and identities were constructed and told to the world through the narrative lens of American missionaries, British anthropologists and Indian administrators. It was only in the 1970s that Nagas started writing about themselves and, interestingly, among the first English books written by Nagas was a collection of folktales titled Folk Tales From Nagaland published by the Department of Art and Culture, Nagaland. Why would the government of Nagaland be so interested to preserve the folktales from the state? Of course, they would want to because Naga folktales were the living repositories of the seen history and throbbing culture of the Nagas. They weren’t just mere stories but a treasure-house of memories, customs, beliefs and everything that would make for Naga existence. Their folktales were their centres of pedagogy as well as their chance at retrieving their history. So once these silences ebbed away, Nagas once again came to acknowledging and reviving these oral tales. Thus, the oral tales became the wellspring of Naga inventiveness.

There are many reasons why there is a need to tap into that reservoir of the past. For one, their present culture is influenced largely by the folklore they have heard. Then it is a way to connect with their roots, “an identity signifier for the Nagas”[6]. Also, this is their opportunity to offer an alternative narrative to written history. “Even for those Nagas writing in English, their stories are either based on or have reflections on the history of the people[which are in oral form].”[7] Many contemporary Naga writers are making use of orality to write to keep culture and tradition alive, they have taken to writing as a way to preserve people stories, they have taken to writing to reclaim and rewrite history, some to interrogate gendered roles, whereas some have taken to writing to understand the unadulterated simple philosophies of life and the possible commingling of fantasy and the supernatural.

[3] Mishra, Tillotima(2011). The Oxford Anthology of Writings from the North-East India; Fiction. OUP: Delhi. pxxii.

[4] Elizabeth, Vivozono. Sentinaro Tsuren(2017). Insider Perspectives: Critical Essays on Literature from Nagaland. Barkweaver Publications: Norway. p17.

[5] Elizabeth, Vivozono. Sentinaro Tsuren(2017). Insider Perspectives: Critical Essays on Literature from Nagaland. Barkweaver Publications: Norway. p22.

[6] Pou, Veio(2015). Literary Cultures of India’s North-East: Naga Writings in English. Heritage Publishing House: Dimapur. p43.

[7] Pou. Veio(2015). Literary Cultures of India’s Northeast: Naga Writings in English. Heritage Publishing House: Dimapur. p43.

(The two stone slabs, believed to be Sopfunuo and her baby, just outside Rusoma village in Kohima. Image via Naga By Blood)

Orality, Culture And History In Contemporary Naga Writings

Contemporary Naga writings have rested comfortable on a triumvirate of orality, culture and history. There is no separating the three as most Naga writings return to history to retrieve their culture and this history has always been oral for the Nagas. A case in point is the quote that follows:

“The four monoliths erected after each feast of merit were set up on the way to the fields. People passed them everyday when they went to the fields. They rested at the foot of the monoliths and recounted the feasts of Kezharuoko, using those moments to recall the great man’s name.”[8]

Spoken by Visenuo, the mother of Atunuo who was being courted by a Tiger man called Kevi in Easterine Kire’s novel Don’t Run, My Love, these lines encapsulate a revival of the cultural tradition that most Nagas, especially the Angami-Nagas, followed in the not too distant past. Kezharuoko, Atunuo’s deceased paternal grandfather was a great man, a man famed in the village for his strength and his wealth. He was etched in the villagers’ memory as the man who hosted four Feasts of Merit for the entire village. “The Feast of Merit was to the Nagas, what the educational degree is to present day students… It was partly the generous philosophy of feeding the poor and sharing of wealth of the entire population, but in most cases, the competitive spirit to climb the ladder of social recognition that prompted the tribal rich people to perform the series of feast of merit and honor round which the wheels of Naga Society revolved…. it is on the feast he has given that his social status depends.”[9].

These feasts are invaluable to building the community and brotherhood as much as it is an assertion of identity. Grandfather Kezharuoko established all that and more and enshrined himself to posterity in the four monoliths he left behind. Erecting monoliths was a significant feat that was synonymous with the Feast of Merit and till date in some Naga villages one can see glimpses of this heritage.

Contemporary Naga writings are rife with resurrection of ancient cultures, tradition and characters inspired from orality. Another instance of orality coming back to life is T. Keditsu’s collection of poems Sopfunuo, which is based on a folktale about a Naga woman called Sopfunuo who, unhappy with her marriage, left her home with her baby never to be found in human form again. Instead, legend has it that they metamorphosed into stones. Even today there are two stone slabs just outside Rusoma village in Kohima which are believed to be this mother-child duo.

Similarly in Renthunglo Shitiri’s poem Of Flight, she recounts, “When we were young,/ cold winter nights,/ drew us to the hearth/ for warmth of the fire/and of Apo’s animated tales, I was drawn to the story of Yama and his maiden angel/knowing not, that was to be my story./Why would angels come down/leaving behind their grandeur/and bathe in the seasonal springs of mortal men? I would often ask./T’was so, for God has destined for Yama,/the one who grew up as a poor orphan/to have a glimpse of Heaven-/apo would patiently answer.”[10]This poem is inspired from the folktale of the Heavenly Maiden from Lotha-Naga folktales. Story has it that Yama, a mortal man, seizes the wings of a maiden from heaven and marries her but ultimately, she flies back to the heavens where her home is.

There are several sub-narratives in the above oral stories- that of history, of the storytelling tradition, of culture, of gender, of voices, of agency, of marriage, of motherhood, of identity, of freedom, of dialogues of power within a framework of patriarchy. Importantly, these recent writings from Naga writers establish the hold of orality on the written word and of how the word renders an alternative historical narrative.

[8] Kire, Easterine(2018). Don’t Run, My Love. Speaking Tiger: New Delhi. p47.

[9] Kire, Easterine(2016). Son Of the Thundercloud. Speaking Tiger: New Delhi. p9.

[10] Shitiri, Renthunglo(2019).’Of Flight’. She: Love And Other Poems. Heritage Publishing House: Dimapur. p46.

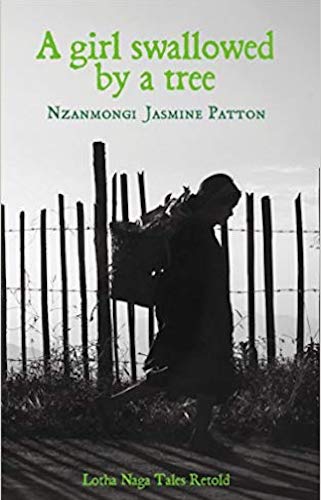

Even my book A Girl Swallowed By A Tree: Lotha Naga Tales Retold was a conscious endeavour to traverse all the bylanes of orality. Cultural practices of Lonhyaka, Hanlamvu, Chumbo etc, which are all celebrated traditions among the Lotha-Nagas are all inscribed in the safety of these folktales. It is an intended effort to bring the reader to the text and not the text to the reader. In the orality of speech and oral traditions, the role of cultural memory, individual creation, myth and history are the multilevel dialogical interactions that take place between the text, context and the community. It is this interaction that has kept the storytelling yarn rolling for generations each time remembering, each time giving dignity to those who would otherwise be forgotten.

For the Nagas, their orality, their folktales and stories are pathfinders to knowing who they are and who their forefathers were. As Sue Monk Kidd said in The Secret Life Of Bees, “Stories have to be told or they die, and when they die, we can’t remember who we are or where we have come from.”

Nzanmongi Jasmine Patton is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Gargi College, University of Delhi. Her areas of interest range from Oral Literature and History, Folklore Studies, Translation, Gender Studies, Culture Studies, Women’s Autobiographies, Indian Writings In English, Classical Literature and Academic Writing. She has published a collection of folktales titled A Girl Swallowed By A Tree: Lotha Naga Tales Retold by adivaani, 2017. Her story, The Sesehampong And The Velongvu, a translation of a Lotha-Naga tale to English was featured in the March 2019 quarterly issue of AntiSerious, an online Literary magazine. Her upcoming children's fiction titled Zeno And Her Song Of The Naga Hills will be out shortly in 2019. She is currently working on a series of illustrated children's folktales.

Read her articles here.

Hallo, I’m a bookseller from Leipzig,Germany and I’ m looking for the title :Charles, Chasie: The road to Kohima. Could you help, where e´we can order the book?

Thanks for answer and kind regards.

Hi Marlene,

I found the book available at this seller: https://www.ilandlo.com/Books-and-DVDs/The-Road-to-Kohima

Hope it helps. Thanks for reaching out.

It is a very helpful source and I would like to have a copy of this book in physical form. Where can I get it?