Feature

Mahasweta Devi’s ‘Draupadi’: A Portrayal Of Resistance

I was 19 when I first read Helene Cixous’ seminal work, ‘The Laugh Of The Medusa’. In the essay, Cixous explores the idea of an écriture féminine, or a style of writing that is marked and shaped by feminine experiences which would, in turn, allow a shattering of the stranglehold male experiences and narratives have on language, literature and culture. It affirmed the need for women to write, emphasising that ‘by writing her self, woman will return to the body which has been more than confiscated from her, which has been turned into the uncanny stranger on display’.

As I read these words, I realised that I had already encountered this mode of writing. Mahasweta Devi’s short story ‘Draupadi’, from her short fiction collection Breast Stories, is an exercise in this feminine articulation — deeply embodied, whispering to us the radical possibilities embedded in our flesh. Before I heard the laugh of the Medusa, it was the laugh of Dopdi Mehjen that rang through, clear, unwavering and unashamed. Dopdi was the first female character I had encountered in literature, who, in the face of unimaginable violence, retained her sense of agency as an act of resistance – despite the most heinous efforts to strip her of it.

Contextualising ‘Draupadi’

Set against the politically-charged climate of West Bengal in 1971, ‘Draupadi’ focusses on a young Santhal woman, Dopdi Mehjen, a feared Naxalite, who, along with her husband, Dulna Majhi, and their comrades, is responsible for the death of Surja Sahu, the landlord in Bakuli. The story, translated from Bengali to English by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, follows the efforts of the local police and army officers, led by the Senanayak, to capture Dopdi, after having hunted down and killed her husband.

To me, ‘Draupadi’, like much of Mahasweta Devi’s work, is powerful not simply because it brings before the reader a story of state violence with such alarming urgency and viscerality, but because it tells us of an unthinkable act of courage – of reclaiming and affirming your humanity in the face of those that seek to divest you of it through unimaginable violence.

Dehumanisation Through Language

Language has the power to reduce individuals and communities to threats or enemies of the state and strip them of their humanity in order to legitimise violence against them. It is what starts the process of turning people into problems that must be solved, or ‘countered’, as Devi puts it. We see it happening around us, in our country and across the globe, where those in power begin to use language that makes some of our friends, neighbours, families seem less than – and we are urged to stop seeing them as human.

Mahasweta Devi explores this aspect skilfully in ‘Draupadi’ where the inability of the State to understand or engage with Dopdi and Dulna’s language works in tandem with the State’s dehumanisation of them through the official language. In other words, what cannot be understood must be translated into terms that are intelligible to the State and its functionaries, and in doing so, Dopdi and Dulna are reduced to ‘a black-skinned couple’ who speak ‘a savage tongue’.

The language spoken by Dopdi and Dulna is deemed unintelligible by the local officers, including the Senanayak, who prides himself on learning and understanding his enemy. Their songs and slogans are seen as so indecipherable, that even ‘tribal specialist types’ from Calcutta are unable to decode them. The story itself opens with two liveried officers discussing Dopdi’s name which is confusing to one officer because it is not part of an official list of names:

‘FIRST LIVERY: What’s this, a tribal called Dopdi? The list of names I brought has nothing like it! How can anyone have an unlisted name?’

This inability to understand their language, their names, their music depicts the inability and unwillingness of the State to reach out and communicate or engage with them. Instead, they are studied, objectified and other-ised, under the watchful eye of the State, by academic specialists and by the armed forces. This refusal to engage with their language, which is part of the process by which they are dehumanised, is also what reduces them to mere bodies, devoid of histories, stories and emotions. They are the ‘black-skinned bodies’ of nightmares – meant to be captured and countered, nothing more.

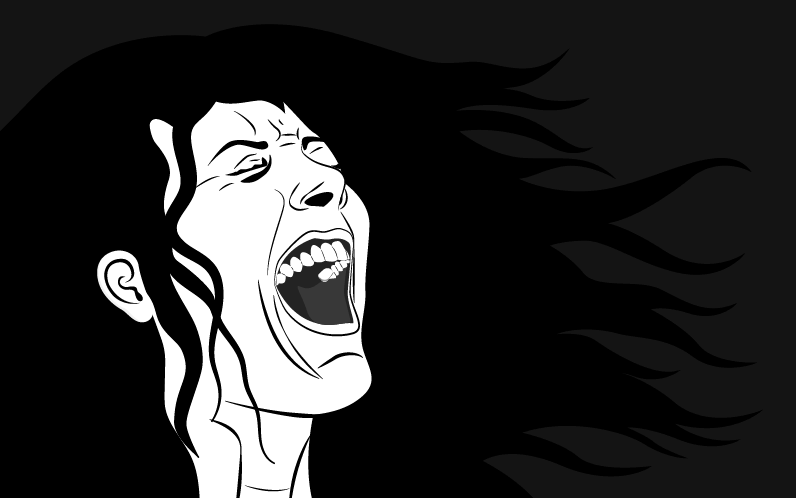

(Image via Hindustan Times)

Silence And The Reclamation Of Language

It is this process of dehumanisation that is continued when Dopdi is captured. Once captured, she must be ‘countered’, degraded and dehumanised, where ‘your hands are tied behind you…all your bones are crushed, your sex is a terrible wound’.

In an effort to get her to speak and betray her comrades, Dopdi is raped multiple times by the local officers. Prior to her capture, Dopdi, aware of the torture she is likely to put be through, steels herself to silence. As she is raped, Dopdi refuses to speak, ashamed when a ‘tear trickles out of the corner of her eye’.

Later, after the men have left, Devi shifts the gaze to that of Dopdi’s, as she surveys the site of violence – her own body. No language can come close to communicating the horror of what Dopdi has been subjected to. And so, Devi forces us to remain with the image of that violence, describing in painful detail, the body of Dopdi after she has been ‘countered’- ‘her breasts are bitten raw, the nipples torn’, ‘her vagina is bleeding’, and her ‘thigh and pubic hair matted with dry blood’.

Here, Mahasweta Devi invests Dopdi’s body with the history, the narrative, that is being denied by the gaze of the officers. Dopdi’s act of refusing to respond or react to the violence being inflicted on her body is an act of rebellion. Through a language that is visceral, Devi captures the violence the State inflicts on Dopdi’s body in its efforts to turn her from a rebellious body to a pliant and submissive one. And, it is through the same language that Devi captures Dopdi’s defiance and subversion as a woman, specifically, a tribal woman who is part of the Naxalite movement.

After her rape, the officers ask Dopdi to get dressed before they can take her to the Senanayak. She walks out, naked, bruised and wounded, refusing to hide the evidence of brutality and unwilling to be shamed. This disturbs the officers and the Senanayak who are unsure of what to do with this woman who forces them to confront their own depravity.

Her disrobing stands in stark contrast to that of her namesake in the Mahabharata. She stands, without a saviour, disrobed and brutalised, but unwilling to bear the shame for a violation committed upon her. She confronts the Senanayak, laughing. Her laughter, bursting forth from her bloodied lips, continues to be unintelligible to the officers, especially the Senanayak:

‘Draupadi’s black body comes even closer. Draupadi shakes with an indomitable laughter that Senanayak simply cannot understand. Her ravaged lips bleed as she begins laughing. Draupadi wipes the blood on her palm and says in a voice that is as terrifying, sky splitting, and sharp as her ululation, what’s the use of clothes? You can strip me, but how can you clothe me again? Are you a man?’

Her laughter and her blood challenge the Senanayak, daring him to do his worst, communicating her refusal to be shamed into submission. Her challenge inverts the dynamic of power and renders the Senanayak powerless. As she bursts into language, the Senanayak find himself bereft of language, too scared to speak at the end – ‘and for the first time Senanayak is afraid to stand before an unarmed target, terribly afraid’.

(Image via Indian Express)

‘Draupadi’ is a story that changed me in elemental ways. It moved foundational blocks and replaced them with something new – shame with hope, fear with agency, and certain silences with a language I had never imagined possible.

As Mahasweta Devi’s words seeped into my skin, and Dopdi’s laughter began flowing through my veins, I realised that Cixous’ prophecy of sorts, her knowledge that women’s writing would ‘wreck partitions, classes, and rhetorics, regulations and codes’, had been realised by Devi in her work. Devi’s genius lay in her ability to help the reader identify with and build empathy for those that are never spoken of in mainstream literature. And, in Dopdi, I ran into that rare character who is vociferous in her condemnation of the structure that dehumanises her, but also offers a way to rupture that structure.

Her laughter, which is both an assertion of agency and an act of condemnation, has been the well to which I turn in times of crises, personal or political, private or public, as a reminder of the possibility of resistance in the darkest of times.

Shweta Radhakrishnan is a professional daydreamer inhabiting multiple worlds, some of which she tries to explore through her writing. She also moonlights as a researcher, a development sector professional and as a documentary film-maker. Apart from this, she also enjoys reading books that her friends tend to view as morbid or melancholy.

Read her articles here.

Very well written. Loved reading this article. I haven’t read anything by Mahasweta Devi but i think i need to rectify this soon.

Thank you so much! I’m so glad you enjoyed the article. Some of my favourite Mahasweta Devi pieces apart from ‘Draupadi’ are – After Kurukshetra and Etoa Muna won the Battle. Happy reading! 🙂

This feature is well-written, cohesive and easy to follow. Thank you for introducing me to Mahasweta Devi. Reading features like this is the biggest validation I need as a woman who believes in the power of words and aspires to write.

Kudos!

Thank you so much! I’m so glad you enjoyed reading the article and that it spoke to you in such a lovely way 🙂