Feature

Coming Out Of The Bookshelf: Why India Needs More LGBTQIA+ Literature

In January 2019, Calcutta, the city of my birth and where I have lived for more than half my life, hosted its first ever Queer Literature Festival. It was a platform for the queer community to come together and occupy space in a way that was not possible before. Lucknow, in February this year, hosted the Awadh Literature Festival, another celebration of the queer community’s contribution to literature and art. Earlier, in July 2018, Queer Chronicles Chennai (QCC) had organised the Queer Lit Festival in Chennai through crowdfunding from its community members and allies.

Queer literature in India is finally coming out of the closet, and one of the biggest reasons is the Supreme Court judgment in September 2018 which decriminalised Section 377, a draconian Victorian-era law, that criminalised sexual conduct “against the order of nature”. While legal recognition is only one battle in the larger scheme of identity politics for the LGBTQIA+[1] community, and the struggles for other constitutional rights remain, it has opened up many avenues for queer expression to be represented, especially in literature.

In contemporary India, where queer communities are being accepted, what space does LGBTQIA+ literature hold? In what ways are the voices of queer people amplified in literature? Moreover, why does India need more representation when it comes to LGBTQIA+ voices in literature and publishing, and how will this change the landscape of Indian literature in the years to come? These are some of the questions that this piece will examine.

[1] LGBTQIA+ refers to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual. The initialism keeps growing to value the human rights, dignity and the right of more non-binary people to self-identify.

LGBTQIA+ Literature Within The Colonial Machinery

LGBTQIA+ literature in India, right from the beginning, has been at tenterhooks: the journey by queer writers or writers writing about queer subjects, as a part of the colonial machinery, has been challenging. This is because most writers were not just confronted by Section 377 but also by constructed ideals of morality, sexuality, culture and obscenity.

In 1922, freedom fighter, Gopabandhu Das published a book titled Poems Written In Prison, in which there are at least two poems that talk about male friendships, and these are described in an intense and erotically charged manner. In the shadow of colonisation, Das couldn’t write about male friendships with sexual overtones; however, later, these poems came to be accepted as an important part of Oriya literature.

In May 1924, a Calcutta biweekly called Matvala, carried a short story by Pandey Bechan Sharma “Ugra” titled “Chocolate”. The story is about Dinkar Prasad, a modern-day Romeo obsessed with poetry and ghazals, and an adolescent boy, Ramesh, who is also Dinkar’s “chocolate” – the object of his erotic affections. Ugra, in his story, twists into a few words what same-sex love means – “He’ll sift through history, finish off the Puranas, and prove to you that love of boys is not unnatural but natural.” The tumultuousness of “Chocolate’s” narrative was centred around sexual ambiguity, rather than “a spirit of hypocrisy”. Both editors of Matvala, as well as Ugra, received several letters after the publication of “Chocolate” – some reproachful of the portrayal of same-sex love, and others full of acclaim. Ugra would go on to publish more such work in Matvala – “Paalat” (Kept Boy), “Hum Fidaye Lakhnau” (We Are in Love With Lucknow), “Qamariya Nagin Si Balkhaye” (Waist Curved Like a She-Cobra), and “Chocolate Charcha” (Discussing Chocolate).

In 1942, Ismat Chughtai wrote her short story “Lihaaf “ (The Quilt) and published it in the Urdu journal, Adaab-e-Lateef. “Lihaaf” is both controversial and celebrated, and takes its readers on a journey of same-sex love, while acknowledging female sexuality and consent, as well as alternative but forbidden desires in the midst of a heteronormative society. “Lihaaf”, in many ways, redefined the relationship between the lesbian identity, the patriarchal Muslim household and the idea of a dysfunctional, heteronormative matrimonial home. It also transformed Chughtai’s own identity as a writer – Chughtai was put on trial for obscenity following this story. In 1946, “Lihaaf” became an object for arbitration in the trial of Ismat Chughtai v. The Crown – an ironic reflection of how same-sex love is often on trial by society’s ideas of morality. Chughtai recorded her experience of this legal battle in an essay titled ‘The Lihaaf Trial’, where she notes with humour and defiance, that the trial would not dampen her spirits or her truth as a writer – “My mind tempts my pen and I’m unable to interfere in the matter of my mind and pen.” To an older writer, M Aslam, Chughtai conveys her motivations for writing about the controversial subject – “[N]o one ever told me that writing on the subject I deal with in “Lihāf” is a sin, nor did I ever read anywhere that I shouldn’t write about this…disease…or tendency”.

LGBTQIA+ Literature Occupies Literary Space

Chughtai’s quintessential feminist move opened up literary space for LGBTQIA+ literature, and many new voices came to the fore. In 1962, Rajendra Yadav, a Hindi novelist wrote a short story called “Prateeksha” (Waiting), depicting a lesbian relationship. Vijay Dan Detha, a Rajasthani author, wrote A Double Life showing a homoerotic relationship between two women who live together in rural Rajasthan. Kamala Das’ autobiography, My Story (1976) is another celebrated work that discusses lesbian desire at a time when same-sex love and desire were morally unacceptable in literature. Vijay Tendulkar’s 1981 Marathi play Mitrachi Goshta (A Friend’s Story) explores lesbian love and coming to terms to one’s own sexuality at a time when conversations around sexuality were not explicit in India. While a lot of literature around lesbian relationships began to come out, it was only in 2003 that R. Raj Rao’s The Boyfriend was published, and was widely considered India’s first gay novel. The book plunges into Mumbai’s gay subculture and “locates queerness in ordinary spaces, such as the Mumbai local trains”.

Even vernacular queer voices have found a space in the literary world. For instance, Kannada writer, Vasudhendra’s book Mohanaswamy (2013) looks at queer identity in India, and not what the consequences of Section 377 were. The text moves through several divides – urban/rural, English/other bhashas (languages) to give the readers a full view of homoerotic cultures.

Trans voices within the realm of LGBTQIA+ literature have been more autographical. Laxmi Narayan Tripathi’s Me Hijra, Me Laxmi (2015) is a notable memoir reflects the life of Laxmi, a transwoman who was born an upper caste man, and the emotional turmoil of transitioning, against the backdrop of India’s struggle against HIV/AIDS. A. Revathi’s A Life in Trans Activism (2016) is another powerful memoir about the author, a transwoman, and her identity and activism.

Post-colonial LGBTQIA+ literature was allowed to occupy its own space within the literary world, whether it be the representation of more queer authors in publishing or that more stories on queer subjects were being written. It expanded the ways in which the lives of queer people were viewed in literature: they were no longer people at odds with the law, they were people who led mundane lives and whose stories were more than battling penal codes and legal provisions on obscenity.

The Question Of Visibility For LGBTQIA+ Literature

While LGBTQIA+ literature has been out of the closet for a long time in India, it’s visibility and positionality within the Indian literary scene is still very spurious. The LGBTQIA+ community stands at the centre of trauma, stigma and discrimination – an intersection that is antithetical to the notion of space and power, and while a lot of Indian queer literature exists, the presence of queer writers and their lived realities is often invisibilised.

So far, Indian LGBTQIA+ literature has stood between the public and private realms, stretching out like a bridge in order to amplify the voices of the community. Like queer people in India themselves, foreshadowed by a draconian law, and a society that is based upon archaic understandings of sexuality, gender and sexual orientation, queer literature in India is “at once an insider and an outsider, a participant and a voyeur, is insubstantial and corporeal at the same time, a figure whose identity is fluid and transient.”

A very pertinent example of this is Abha Dawesar’s Babyji (2005) that is set in the 1980s, against the backdrop of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations and the protests against it. In Babyji, 16-year-old Anamika Sharma, who sits at the heart of upper caste privilege, indulges in same-sex relationships with three women, and in the midst of these relationships, discovers her sexuality while also grappling with issues of caste.

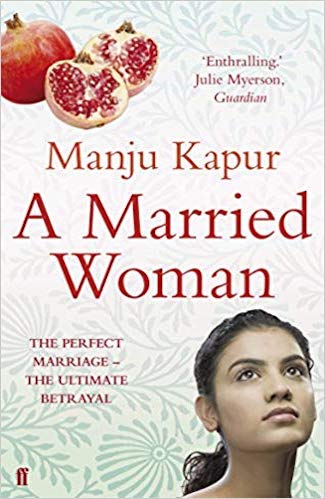

In Cobalt Blue (2006), writer, playwright and director, Sachin Kundalkar pieces together the narratives of a brother and sister in a traditional Marathi household, who fall in love with the same man, a paying guest in their house. In Manju Kapur’s A Married Woman (2002), the reader sees the female protagonist, Astha’s anguish and repression within a traditional, arranged heteronormative marriage as she discovers her latent sexuality with the widow of a political activist. Kapur weaves together the narrative of a lesbian relationship in the backdrop of the Ayodhya communal riots – indicating Astha’s internal strife, unrest and struggle with understanding her own sexuality.

LGBTQIA+ literature in India, in the pre-decriminalisation era, is an exercise in amplifying the voices of the community and simultaneously, diminishing the visibility and power of queer protagonists and writers alike. All the protagonists in Babyji, Cobalt Blue and A Married Woman are hidden figures: they don’t exist as queer subjects, and their sexuality is a mysterious, clandestine subject. Whether it be Anamika in Babyji, the unnamed paying guest in Cobalt Blue or Astha in A Married Woman, they live in cities – visible in everyday lives but wrapped in the anonymity and invisibleness of large cities. This is a haunting reflection of what a repressive, draconian law had done to the community: pressed their identities into layers of obscurity and ignominy.

The public visibility of the queer community has grown exponentially after the Supreme Court verdict of 2018, and yet, queer realities are not adequately reflected in literature. A lot of mainstream literature continues to be focussed on heteronormative love and desire written by cisgender, straight authors. There is a definite need to fill the vast gap within Indian publishing and literature where queer people write their own stories, without being eclipsed by past notions of what was considered ‘normal’ in the Indian literary scene.

This need stems from issues of diversity and representation, but also to intentionally break away from the notional public/private divide that has held back queer writers from creating protagonists who exist within narratives as queer people. This will also prevent LGBTQIA+ sexuality in stories from being this will-o-wisp, unattainable mysterious object that might exist only in an alternative, fantastical world.

To do this of course, we will have to open up our hearts and bookshelves to authors like Suniti Namjoshi, an openly lesbian author from India, who has written several books around female sexuality, queerness and feminism; publishing houses such as Queer Ink, that provide the community an exclusive platform and space for writing and publishing LGBTQIA+ literature, and online forums such as Gaysi, that portray stories of the LGBTQIA+ community. Doing this will ensure that the landscape of Indian literature expands to be more representative, diverse and inclusive.

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.