Feature

The Rise And Fall Of Hindi Pulp Fiction

Prasanna Sawant

January 10, 2019

The A.H. Wheeler bookstalls are less of a novelty and more a part of life for the millions of people travelling on the Indian railways and the Dadar Railway Station is no different. Amongst the newspapers and the latest thriller and romance novels, a grainy and brightly coloured printed book stands out. As people mill around, engrossed in their smartphones, a 50-something passer-by stops for a moment, covertly looks at the cover featuring a smug villain, a scantily-clad woman and a trigger-happy hero, and seems to be remembering something from his youth as he smiles to himself. However, after one look, he moves on without buying anything and his smartphone claims his attention once again. The book lies forgotten along with a part of our literary history.

The book is part of a popular genre of Hindi literature of the 70’s- Pulp fiction. Aptly named because they are printed on grainy “pulp” paper, their outlandish titles and juicy covers made them easy to spot and they were a prominent part of almost every bookstall. With their twists, fiery dialogues and over-the-top scenes, these books not only managed to engross the readers, but also played the role of an entertaining companion during lonely train travels, and were easily and cheaply available at most railways stations.

The ’70s were a period of change for India. We had left behind the haze of colonialism and the glamour of freedom was slowly fading away as we realised governance is not as easy as we thought. We were still aching from the displacement and atrocities of the Partition, had already fought three wars- two with Pakistan and one with China- and dealt with several domestic insurgencies. The economic conditions weren’t much better- industrial production had slowed down, the labouring class was rebelling under the atrocities of the merchant class, unemployment was on the rise and Emergency had added fuel to the fire. People were naturally agitated and needed a way to escape their morose life.

Pulp fiction captured this essence and these thrilling tales of suspense and romance gave the people a way to live vicariously. While the stories and characters varied, the themes of most of these books were fairly similar with black magic, soft porn, illicit affairs, scandalous women, daring heroes and hard-boiled villains featuring in many of them. Pulp fiction had something for everyone. The post-independence war-weary aam aadmi dreamt of larger than life characters who went on adventures, flirted with beautiful women and lived seemingly charmed lives without the daily struggle.

The typical Indian housewife’s life was supposed to revolve around her husband and family, and reading pulp fiction allowed her to escape this mundane life, even if it was for just a few hours. Bored housewives found themselves enthralled by female characters who drank, smoked, and lived seemingly more interesting lives than them. At a time when TVs were not as common as they are now, these romanticised versions of women were the only form of entertainment available.

With a ready market for their books, authors like Surender Mohan Pathak and Ved Prakash Sharma churned out books at an alarming rate, and sold as many as 500,000-600,000 copies without any publicity.

Despite its popularity amongst the masses, people who prided themselves on their “literary” intellect scoffed at pulp fiction and treated it as literature’s stepchild. By the 90s, English emerged as an aspirational language for the masses and people were eagerly taking to books written in English. As Indians strove to make their place in the world, reading in English became more prestigious and people were suddenly embarrassed to be seen reading Hindi and pulp fiction even more so. And those who did continue to read them did so covertly, often wrapping the books in brown paper so no one could tell what they were reading.

The already shrinking market for Hindi pulp fiction was dealt a big blow with the entry of Chetan Bhagat, who effectively cornered the market with his relatable books set in India and written in simple English. Bhagat also set off a literary movement in the country with other authors like Durjoy Datta, Ashwin Sanghi and Ravinder Singh writing novels which appealed to people who wanted to read in English but didn’t enjoy the highbrow literary fiction of authors like Amitav Ghosh and Arundhati Roy. Even in small towns, Bhagat, Datta, Singh and Sanghi took over the shelves previously occupied by Hindi pulp fiction.

(Image via News18)

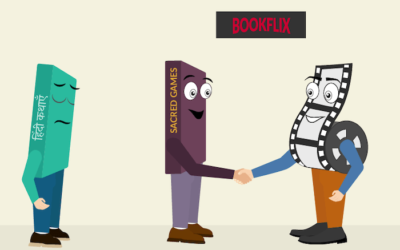

Even if pulp fiction could have handled the competition from English books, it couldn’t keep up with technological advancement. With the proliferation of TVs and smartphones, people had access to other forms of entertainment. As our attention spans reduced, so did our inclination to read books. Instead of reading Hindi pulp fiction, we took to watching saas-bahu serials and cat videos on the go. Hindi pulp fiction couldn’t possibly compete with such visual media.

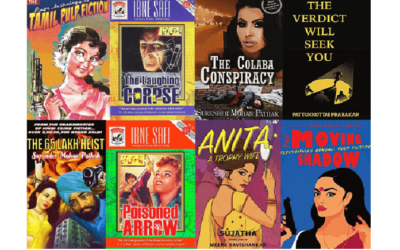

While Hindi pulp fiction may have decreased in popularity, it is not dead. Surender Mohan Pathak continues to release books, which are now published by Penguin. Seeing their potential, Penguin has also released an English version of Pathak’s latest book, Conman. Two more books in Pathak’s popular Vimal series are slated for release this month. Perhaps, the adoption of Hindi pulp fiction by mainstream publishers will give it a much-needed thrust, even more so as their English translations make them ‘cool’ again. While earlier it seemed that the future of Hindi pulp fiction was bleak, there is now hope. Hindi pulp fiction plays an important role in India’s literary history and we do hope to see it regain some of its lost popularity.

Prasanna is a human (probably) who makes stuff up for a living. When she’s not sleeping or eating, you’ll find her in the quietest corner of the library, devouring yet another hardbound book. She vastly prefers the imaginary world to the real one, but grudgingly emerges from her writing cave on occasion. If you do see her, it’s best not to approach her before she’s had her coffee.

She writes at The Curious Reader. You can read her articles here.

It is strange that you label once so popular fiction as pulp fiction because it is published on the not so expensive paper called lugdi or pulp. The author has the knowledge of a Sharma and a Pathak but they are only what is there now. Go deep in the history and you will label it ” Hindi popular fiction”.