Feature

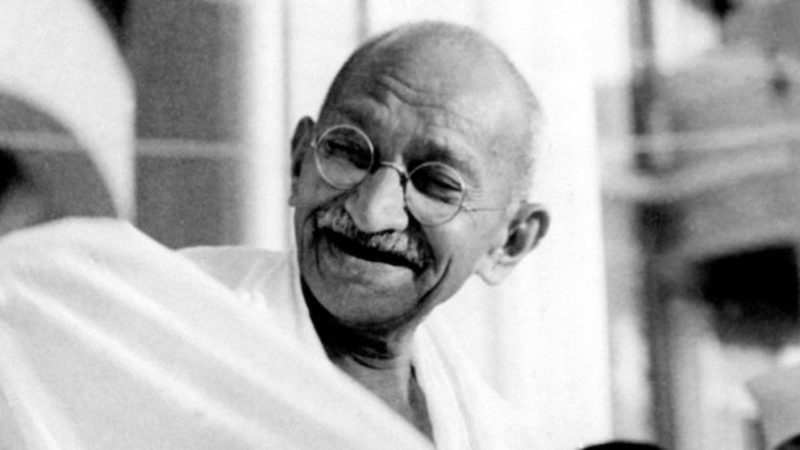

Why Gandhi Is Still Relevant

When I was in college, I signed up for a course called Making of the Modern World. My professor was talking about how Thoreau inspired Gandhi, who had then been an inspiration for Martin Luther King Jr’s own civil disobedience movement. I was a freshman at an American university and my professor was a middle-aged white man. As he spoke about Gandhi’s political and personal philosophy and its far-reaching impact on the world, I sat up straighter at my desk and could see other Indians and Indian-American students in the large auditorium straightening up too. Gandhi and his legacy were a source of national pride.

But then, in response to a question from a student, the professor told us about Gandhi and his belief that people should lead a celibate life in order to be of real service to the nation. He told us about how far Gandhi took his interest in this idea of celibacy – of how he had his grand-nieces and other young women spend the night in his bed, naked, just to test how strong his self-control was. Suddenly the auditorium was filled with uncomfortable twittering – a dozen hands flew into the air and the professor fielded several questions before encouraging us to read about Gandhi for ourselves. I left the lecture feeling convinced that this was a conspiracy to disgrace our national hero. But it turned out my professor had been right, and the more I read about Gandhi on the Internet, the more uncomfortable and awkward I felt about him.

Today, Gandhi is one of the most written about Indians. It does not surprise me that so many of his contemporaries, family members, biographers, journalists and columnists have written about him because Gandhi’s life was not a simple one to examine and his influences have been far reaching. Despite everything we know about Gandhi, he persists in our collective consciousness as someone worthy of our continued interest, respect and for many of us, even affection. But as I read more about Gandhi, I found my admiration for him waver and I began to doubt his entire legacy.

Gandhi’s Treatment Of Women

Gandhi’s brahmacharya experiments were clearly extreme, and, as Ramachandra Guha, in his book Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World, puts it – “inexplicable and indefensible”. Had Gandhi been alive now, his reputation and legacy might not have survived the fierce and instant judgment of the #MeToo movement. In fact, even in Gandhi’s own time, some people in his immediate circle objected openly to his bedtime routine and resigned from their positions to express their strong disapproval.

But there were other things that bothered me about Gandhi and his treatment of the women in his life. As I read his autobiography, My Experiments With Truth, I got the impression that when an idea caught Gandhi’s fancy, he would throw himself completely into it, regardless of how it impacted anyone else in his life. Gandhi admits that he “was a cruelly kind husband” who thought of himself as his wife’s teacher and forced her through all his radical experiments with celibacy, simple living, nutrition and untouchability. There is a certain irony in how violently he seemed to take up every idea or notion, how harshly he treated his own family and yet how committed he was to his ideas on ahimsa and love.

While Gandhi did a great deal to encourage women’s participation in the public sphere, we can also see from his letters, that he believed women should bear the responsibility for sexual assault upon themselves. He seemed to encourage women to even give up their lives to protect their honour, rather than live with the shame of it. According to an article in the Guardian, Gandhi once personally cut off the hair of two female followers when he heard that a young man had been harassing them. He wanted to make sure the “sinner’s eye” was “sterilised”.

Gandhi And His Armour Of Truthfulness

Gandhi was an extraordinary politician because, unlike our modern-day politicians, he went to great lengths to be truthful, honest and open. When rumours began to swirl about Gandhi abandoning his vow of celibacy and enjoying the company of women, he addressed the rumours directly in an essay titled ‘My Sex Life’ from the book My Sex Life And Other Thoughts On Sex, Love, And Temptations. Can you imagine a modern-day politician or public figure writing an essay with that kind of title today? Most want to avoid the subject entirely, unless it is to sully the reputation of their opponent.

In the essay, Gandhi confronts these rumours head on. He defends Sushila Nayar, one of the first women to participate in his experiments with celibacy and insists that he has not given up his vow at all. He explains how the vow allows him to ‘serve womankind’ because women felt so comfortable in his presence they no longer needed to be shrouded behind a veil and were able ‘[to] face[d] one another as equals’. I found the essay remarkable. While it might be very naïve, it was not apologetic, and it was also not rude and dismissive of the rumours. There is a clear intent to reach out to his reader and have them understand his points of view. By being so open and transparent about his life, Gandhi was able to control the narrative of any scandal and soften its blow.

If my previous criticism of Gandhi had been that he was dogmatic and frequently dove into ideas and insisted on acting on them at the cost of his family, Gandhi again makes up for it by laying all his flaws out for us to see in advance. In his autobiography, Gandhi tells his readers of the time he made his wife return jewellery that had been sent to them as a gift. Kasturba does not yield so easily. She reminds him of the time he forced her to return the jewels that her parents had left her. She chastises her husband and says that he seems to be making “sadhus of [her] boys”, leaving her with nothing to pass down to her daughters-in-law. Irritated by her objections, he asks her sharply, “Is the necklace given to you for your service or for my service?” Kasturba does not miss a beat. She says, “I agree. But service rendered by you is as good as rendered by me. I have toiled…for you day and night. Is that no service? You forced all and sundry on me, making me weep bitter tears, and I slaved for them!” We know of this exchange thanks to Gandhi himself. In his own writing, Gandhi’s honesty and frank examination of his own life disarms the reader. He captures our imagination today because of his firm adherence to the truth regardless of how the truth might impact his reputation. Curiously, the truth works as a coat of armour for him.

(Image via Listverse)

Gandhi And His Willingness To Grow

Another corollary to this point is how open and accepting Gandhi was of debate and disagreement. In Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad’s memoir India Wins Freedom, Maulana writes about when Gandhi and he had very different opinions on when to launch a mass movement that was later called the Quit India Movement. Gandhi was persistent about his timeline and wrote Azad a letter telling him that their difference of opinion was so deep that if Gandhi was to lead the campaign, then he would need Azad to resign from the Presidency of the Indian National Congress as well as the Working Committee. It was a very upsetting letter but when Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel intervened and explained Azad’s position on the issue, Gandhi made a magnanimous about-turn and invited Azad for a meeting where he said of himself ‘the penitent sinner has come to Maulana’. This graciousness in defeat and willingness to accept his opponents’ points and ideas when they are right is extraordinary and is a skill we might benefit from in our polarising times. It comes from Gandhi’s true belief in the equality of all.

Thanks to the vast body of literature available on Gandhi and his own writing, we can see how he changed his opinion on various things slowly over time. While Gandhi was certainly capable of going overboard with his idealism, even to the point that his own disciples found it a strain to keep up, Gandhi’s earnestness and dedication to ideals make him an eternal curiosity. It is easy to be cynical about his steadfastness to all his various ideals, but as you read his work, it is clear that sticking by what you believe requires incredible moral courage and character. It takes a certain amount of fearlessness and confidence to be open to debate the things you believe in and change your position based on new information or insight.

Gandhi In Our Modern Times

While Gandhi made a great deal of effort to be as perfect and pure as he possibly could, he clearly was a man with flaws, like any other person. Naturally, many have wondered if he still deserves such a lofty title as Mahatma? This question is nearly impossible to answer because it depends on everyone’s individual definitions of what makes one a Mahatma. I think the question should be – has Gandhi left anything behind that still remains relevant to us in our current lives? This is a simpler question to answer. The answer is yes – he has. His philosophy and ideas on non-violence and how communal relations can remain peaceful are incredibly relevant in today’s climate. But more than that, Gandhi left us powerful lessons on the manner in which he lived his life in the public sphere.

———

In today’s political and social scenario, this feels like an impossibly tall order. But the fact that a flawed human and not some mythical Mahatma was capable of all this is vaguely reassuring. Placing him up on a pedestal does us more harm than good. There is much to be learnt from his life – the risk of taking ideas too far, how the blind pursuit of ideals can hurt those closest to you just as much as one wilfully hurting them for more baser pursuits, how the truth can shield you, how openness and the willingness to learn can transform you and the world around you. These are still important bits of Gandhi’s legacy.

Saisudha works at a small democratic school in Bangalore where she 'teaches' history, economics and anything else the children are interested in. She loves her job and one of the reasons she loves it is because she can drag the books she loves into conversations and lessons she plans. When she is not working, she is either reading or listening to books and podcasts. She has a particular soft spot for historical fiction, creative nonfiction, but mostly children's literature - even picture books get her excited. Her favourites are any books by authors like L.M. Montgomery, E.B. White, Kate Di Camillo and Neil Gaiman. Nothing can beat the high she gets when a child comes rushing back to her with a book that she recommended, telling her how he or she loved it and why.

Read her articles here.