Feature

Wicked Witches And Evil Stepmothers: Stereotyping Female Villains In Fairy Tales

Ihad heard and read my share of fairy tales while growing up – the popular English ones, the rich repertoire available in Bengali, as well as some translated from other Indian languages. But I’d never stopped to consider the values children pick up from fairy tales, unquestioningly assuming that they stop influencing us as we grow older.

Over time, however, I’ve had to accept that fairy tales do actually transmit certain values that get further entrenched in our psyche through socialisation. I’ve also noticed a remarkable similarity between fairy tales from different regions of India, and those presented by the Grimm brothers and Hans Christian Andersen. They echo each other in their portrayal of the villain as feminine. They also resemble each other in the portrayal of males who act as saviours or heroes and arrive to save the damsel in distress.

But what happens when the impact of these tropes extends beyond the realm of fantasy and influences choices and decisions in real life today?

The Villain As Feminine

In the fairy-tale land of possibilities, good and evil are central themes. The aim, supposedly, is to instil a belief in children that evil always loses out to good in the end. Whether we talk about the fairy tales from the Western world, or their Indian variations, there’s always a villain to be defeated and punished. That’s pretty much what guides social justice activism as well – a belief that justice must finally prevail. Also, evil does exist in real life and it’s good for children to be aware of that. My problem lies in the identity of the villain. More often than not, it’s a woman who is presented as an evil witch or a cruel stepmother or a combination of both.

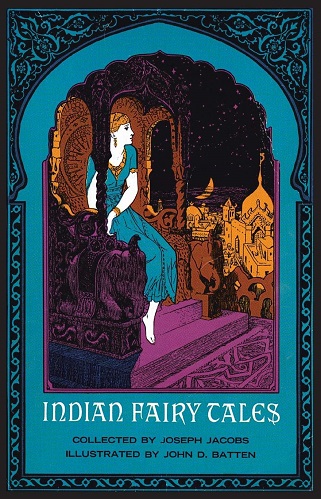

Take the trope of the evil stepmother, for example. The West has the well-known evil stepmothers of Cinderella and Snow White. Closer home, we have ‘The Wicked Stepmother’ (Folk-Tales Of Kashmir) and ‘Punchkin’ (Indian Fairytales). Both stories depict the stepmother as a cruel woman who wants nothing more than the death of her stepchildren, a far cry from the image of the nurturing mother.

‘Punchkin’ also portrays a certain amount of bias against women who are different from the clichéd wicked stepmother. The youngest of the king’s seven daughters is the most intelligent. She is also the one who gets into maximum trouble, to be finally saved by her son. The message, as I understand it, is that a woman who uses her brains invites trouble and requires a male to ultimately come and rescue her.

(Image via Pinterest)

The Myth Of The Wicked Witch

The other typical villain in fairy tales is a witch or an ogress, who might even double up as the cruel stepmother. This witch or an ogress manages to become the father’s second wife through the clever use of her guiles. It is only then that she lets her evil side come to the fore.

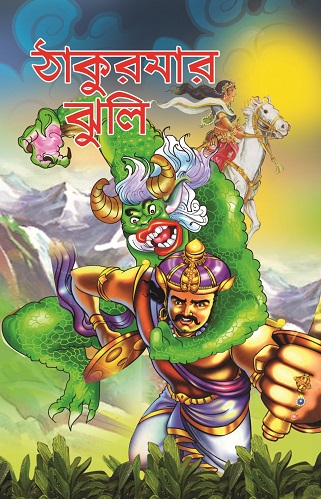

The popular Bengali fairy tales of ‘Lalkamal Neelkamal’ and ‘Dalimkumar’ (from Thakurmar Jhuli) are good examples here. So is ‘The Son Of Seven Queens’. In ‘Lalkamal Neelkamal’ and ‘Dalimkumar’, an ogress manages to enchant the king and become his second wife. In ‘The Son of Seven Queens’, it’s a witch who mesmerises the king with her beauty. He’s so bewitched that he gives her the eyes of his seven queens as a gift to convince her to marry him. What is truly unfortunate is how the story explores this act. It chooses to focus only on the witch’s jealous aggression against the seven queens in her demand for their eyes. The king is portrayed as a victim of her seductive beauty in the form she assumes for him. And sadly, there’s no condemnation of his cruel act.

Each of these three stories portrays a clear bias against the female. Dalimkumar, a prince tortured by an ogress-turned-his-stepmother, does not become a helpless victim. He roams around on his flying horse to save a princess in distress in another land and returns to kill the ogress, resurrect his mother, and save the entire kingdom from the wicked designs of the ogress.

This is in sharp contrast to our versions of the damsel in distress in stories like ‘Ghumantapuri’ and ‘Sonar Kathi Roopar Kathi’ from Thakurmar Jhuli. When a princess falls prey to an ogress or a witch turned stepmother, she’s just a helpless victim. A daring and determined prince must arrive to rescue and marry her. However, a boy who faces the same situation manages to win against the evil spirit by himself.

‘Lalkamal Neelkamal’ takes this a step further to justify matricide as an act to be celebrated if the mother is an ogress who does not like her stepson. Neelkamal, the son of the ogress, is so fond of his half-brother Lalkamal that he kills his mother to save his brother (Lalkamal). Stepbrothers bond while stepsisters don’t. I’m not thinking of just Cinderella at this point. Both ‘The Wicked Stepmother’ and ‘Punchkin’ show the stepmother’s daughter spying for her mother to make life more difficult for her stepsiblings.

What Children Learn

It is important to note that this depiction of a stepmother as a heartless villain continues to have ramifications even today. According to The Telegraph, this continues to be a prevalent social myth that needs to be busted. Research indicates that the wicked stepmother myth automatically paints the father’s second wife as a heartless villain even before she gets a chance to win her stepchild’s trust.

This entire landscape of the villain as feminine becomes even more problematic when we bring into focus the characteristics assigned to this embodiment of evil. She’s often poor, if she’s human rather than a witch or an ogress. And, she’s almost inevitably ugly, capable of camouflaging her looks. Everything that children don’t need to learn and believe: gender bias, looking at poverty as evil, equating ugliness with wickedness.

An Inspiring Exception

‘Kiranmala’, a story of three siblings, from Thakurmar Jhuli, is my favourite fairy tale. It’s the only traditional fairy tale I know where Kiranmala, the sister, saves her brothers, Arun and Barun, and a lot of other princes and their people.

This is an exceptional fairy tale due to many reasons. Not only does it show a woman saving all the men, it also gives the readers a heroine who succeeds because of her grit and her brains, rather than simple muscle power. This presents her in a different light from the usual brawn power associated with the men in fairy tales.

Given the realities that women have to face in the world every day, it is necessary to create stories that encourage them to stand up for themselves and break through existing stereotypes. It is because of this that we need more Kiranmalas in the land of fairy tales today.

Paramita Banerjee, an Ashoka Fellow, is a black coffee drinking social activist working with marginalised young people to enable them to emerge as change-makers. She dreams of using her pen to ruffle status-quoist feathers. She has a number of published translations and academic articles to her credit. Among them, a translation of Mahasweta Devi’s short stories for children (Our Non-Veg Cow And Other Stories). Her most recent articles appear in the following anthologies: Friendship As Social Justice Activism: Critical Solidarities In A Global Perspective; The Idea Of The University: Histories And Contexts; (Re)Claiming Lesbian Feminism.

Well written, thought provoking. There is perhaps not a single soul who hasn’t grown up with fairy tales. However, very few have looked at them from this angle. Hopefully, the next generation will see gender neutral stories that don’t fail to keep the magic of fairy tales intact.

Thanks so much, Nandita, for your careful observations. I couldn’t agree more on the point about future generations.

Thankfully, magic exists beyond the stereotypical gender binary – as some experiments reflect. As our very own “Kiranmala” demonstrates, for that matter!

Well written. Thought provoking.

Work in this direction needs to continue

Thanks so much!

Intrigue..! Good piece of writing. Rolls a sets of questions in me –

The times when those books were written, the authors (presumably mostly male), In 16th century Intelligent perceptive women were burned alive as evil witches. How with time things change.

Grimm’s Sneewttchen original has a queen who longs for a beautiful daughter and dies at childbirth – but later editions after 1819 describes the queen who longs for daughter and becomes jealous of her beauty and is shown as a step mother. Similarly in Hansel and Grethel – the father who encourages the mother to abandon the daughter into jungle – after,1840 – the mother is shown in all its edition as step-mother. Male authors wanted to protect the image of biological mother as “good” obviously.

Now there are new-modern feminist authors/ writers, who wants to re-write fairy tales – showing witches as good characters..!

Still witches and step-mothers are only wickedly manipulative yet NOT downright evil as serial killers (mostly 99% men) – who brutally kill, rape and/or murder for pleasure – the psycho types. May be with time – in coming centuries we may see new breaking grounds there too – where we find real and literary characters who act like such “men” villain ..!

Other fascinating thing is the story-telling dwelling around fantasies and super-hero (heroines?). It also shows the collective-psychology of poverty stricken self-esteem – that draws trends around mass popular hysteria in accepting fe/male “ideal” perceptions around the key reader identifying with certain traits of key protagonist – “beautiful princess/ brave prince. ”

No wonder to protect and make “witchery” good & famous – it is a new religious cult in Europe/ UK/ US.

Thnk you, Raj, for the well-though out and informative observations! You should be writing a piece on it, methinks. I’m serious.

Enjoyed reading this thought provoking article of yours. These negative portrayals of women are reflections of a patriarchal system. Kiranmala may be an exception. But it is high time women are shown in positive light (just as they are) as suggested in the concluding lines.

I have come come across ‘step mothers’ who are very humane and caring in real life. Shared your story with my daughter and friends.