The Epistolary Nature Of Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Devanshi Jain

May 26, 2018

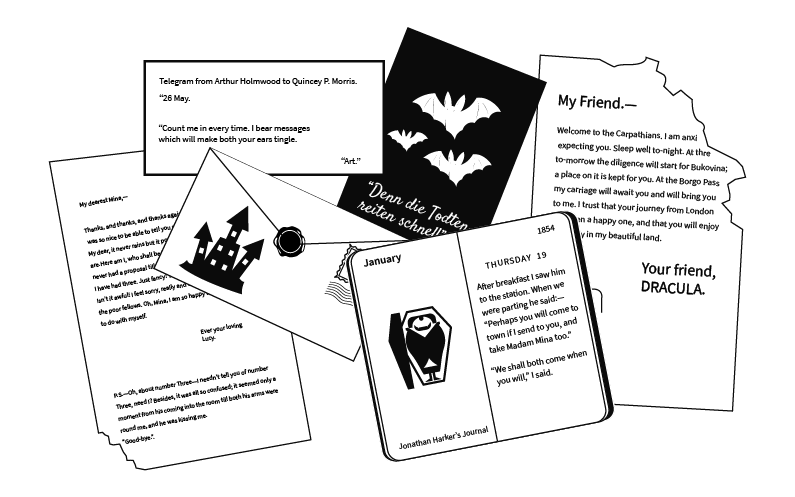

Perhaps, the biggest advantage of using this style is that the author can introduce different voices with ease. As there is no omniscient narrator, we get a better understanding of the characters since we get to hear their own perspectives. As readers, we form a greater connection with the characters as we are privy to their private correspondence which can provide us with intimate details which would seem extraneous in any other form.

Similarly, Mina Murray and her friend Lucy Westerner’s correspondence serves the purpose of introducing their relationship and Lucy Westerner’s voice paints the picture of a carefree girl in the prime of her life, with everything to look forward to including the promise of true love. This works particularly well because had this not been an epistolary novel, we would never have had a chance to hear her voice through her letters. Instead, the author would have had to rely on Mina’s impressions of her and perhaps develop her character through some small incidents.

(Source: Documentary Tube)

Harker’s journal also sets the stage for one of the larger themes of the book- that of the rational versus the supernatural. He chronicles how he slowly comes to fear and understand the true nature of Count Dracula. He shares the experiences which helped him come to the conclusion that Dracula is a vampire and his interactions with the Count introduce us to Dracula’s ill-intent. We know that Dracula will be the main antagonist in the book even if we may not completely know who or what he is.

(Photo by Universal/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock via Variety)

The epistolary nature of Dracula successfully develops dramatic irony- the reader knows the significance of the events long before the characters. We readers are the only ones who are able to compile the narrative fragments to make sense of events as they unfold. As Dr. Seward struggles to understand why Lucy Westerner is fading away, the reader can guess based on the evidence of the wounds on her neck, the presence of a bat and our knowledge of Harker’s journal, that it is because of Dracula draining her blood that she is ill. Later, we realise that Mina has also fallen victim to the Count before the others do even though they have finally understood Dracula’s true nature. This is, perhaps, the most frustrating part of this novel. We constantly feel like hitting the characters on the head to make them believe the evidence in front of their own eyes. It is further compounded by the fact that all the characters are intelligent and well-educated people.

As the novel deals with supernatural themes, the epistolary structure and use of different narrators with varied viewpoints who corroborate each other’s narrative lends an element of realism to the story. Harker too finds himself questioning his reality until it is corroborated by the experiences of others. After Harker successfully escapes Count Dracula’s castle, Mina finds him a shell of his old self. He constantly questions whether he merely imagined his encounter with the Count. It is only after Professor Van Helsing confirms his experiences with and his conclusion about Dracula that Harker expresses a sense of relief as his views are validated and he no longer questions his sanity. “She showed me in the doctor’s letter that all I wrote down was true. It seems to have made a new man of me. It was the doubt as to the reality of the whole thing that knocked me over. I felt important, and in the dark, and distrustful. But, now that I know, I am not afraid, even of the Count.”

(Still from the movie Dracula via Nerdist)

Devanshi has been reading ever since she can remember. What started off as an obsession with Enid Blyton, slowly morphed into a love for mystery and fantasy. Even her choice of career as a lawyer was heavily influenced by the works of Erle Stanley Gardner and John Grisham. After quitting law, and while backpacking around India, she read books on entrepreneurship, taught herself web design and delved into social media marketing. She doesn’t go anywhere without a book.

She is the founding editor of The Curious Reader. Read her articles here.