Feature

The Criticism Against Dahl: What We Failed To Understand As Children

Nirbhay Kanoria

September 12, 2018

Roald Dahl is a prolific children’s author who has delighted young and old alike for decades. Most of his works are considered classics in children’s literature and you’ll be hard pressed to find someone who hasn’t read his work. But, as much as children have loved his work, there has been a lot of criticism against Dahl, largely for portraying unsavoury themes and elements, such as anti-Semitism, misogyny and bigotry in his works. He also holds the honour of being fired by his publisher, at the height of his popularity, due to his terrible behaviour and views.

However, criticism may not always be well-founded. Personal biases, context and a lack of understanding can affect the way someone’s work is perceived. I grew up on Dahl’s work, so I decided to reread some of his most famous books to investigate the criticism and see if there is any merit to it.

BOIL THEIR BONES AND FRY THEIR SKIN

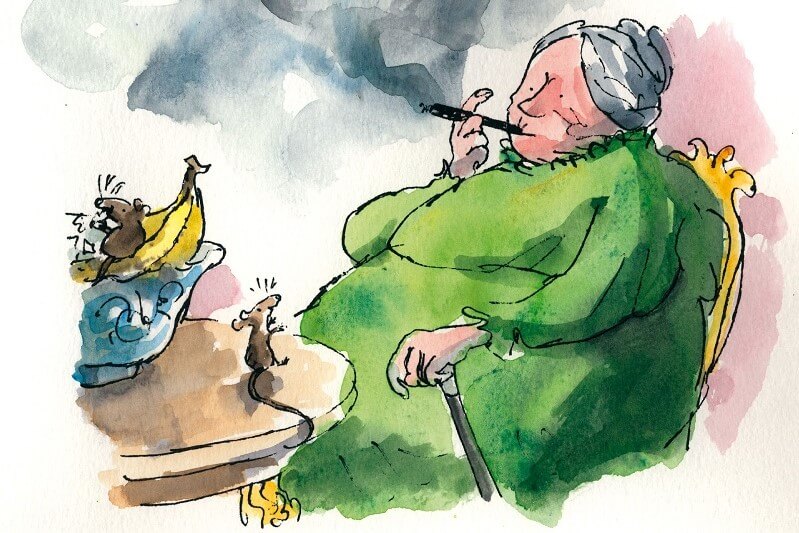

I first reread The Witches, and I was thrilled to be reading a Dahl again; his books had taken up much space in my library during my childhood.

The book is primarily accused, by multiple critics, of misogyny. By stating that ‘a witch is always a woman’, critics think the book teaches young boys to think of women as witches and build a life-long distrust of women. I find myself unable to completely agree with this, for the simple reason that Dahl clearly writes that ‘a ghoul is always a male’ and that not all woman are witches, and in fact, ‘most women are lovely’. He doesn’t say that one gender is dangerous and the other is not, but that witches disguise themselves as women to hide their true identity. Also, throughout the book, the unnamed protagonist relies on, loves, and respects his grandmother, a strong female character in a children’s book, who helps him destroy the witches. I read the book more as a case of good vs. evil, and did not pick up on the apparent misogyny.

Having said that, Dahl could have just done away with the ‘witches have to be women’ aspect of The Witches and the story wouldn’t have suffered, but I do feel we should extend him that creative license.

Context is an important aspect when it comes to books, and given our current sensibilities, it definitely caused me to raise my unibrow when I read The Witches. I was rather shocked that the stalwart Norwegian grandmother was a chain cigar smoker! And even offered her eight-year-old grandson a puff! In a day and age when health and the dangers of smoking are being spoken about more than ever, it definitely did not go down well for such an important character to advocate smoking and say “I don’t care what age you are, … you’ll never catch a cold if you smoke cigars”. Similarly, the allusion that because a witch is bald she has to wear a wig as else she will not be perceived as a ‘true women’ is rather a blow to the feminist cause which is, and as it should be, all about choice and pride in one’s body and said choices.

(Image Credit: Pinterest)

OF COURSE, THEY’RE REAL PEOPLE. THEY’RE OOMPA-LOOMPAS

Done with the bald, clawed, square-footed witches, I moved onto what was probably my favourite childhood book, Charlie And The Chocolate Factory– the magical story of a poor boy and an eccentric chocolatier. I couldn’t contain my excitement, and then my disappointment. I had to agree with the critics– the book is one hot mess, and I’m shocked that it was ever published to begin with.

The enigmatic, intelligent, and cuckoo Mr. Wonka holds a competition, the five winners of which get to visit his chocolate factory- only for all, except one, to be shamed, tortured, and humiliated for simply doing what children do. Wonka not only does nothing to protect most of the children but delights in their suffering. There is an unfortunate boy, by the name of Augustus Gloop, who is quite overweight- and when tempted by a river of chocolate, he begins to drink the chocolate and subsequently almost drowns in the river. Instead of trying to save him, Mr. Wonka giggles and his precious oompa-loompas sing,

“..The great big greedy nincompoop!

How long could we allow this beast

To gorge and guzzle, feed and feast

On everything he wanted to?

Great Scott! It simply wouldn’t do!

However long this pig might live,

We’re positive he’d never give

Even the smallest bit of fun

Or happiness to anyone.”

I find it shocking that Dahl so callously wrote about an overweight boy and downright poked fun at him only because of his weight, and even went to the extent of alluding that because of his weight he’d never provide happiness to anyone. Whether then, or now, children need to be taught to love their body and appreciate themselves even if they are overweight, or like to chew gum, or watch TV, and not feel that they are lesser than someone else because they have certain habits or look a certain way.

A large part of the criticism against Dahl was because of his treatment of the oompa-loompas, who unsurprisingly, originate from some wild and dangerous land (presumed to be Africa). Willy Wonka is their saviour- much like the image white colonists created for themselves. He shamelessly uses them for experiments, letting one’s beard grow uncontrollably, or letting 15 of them turn into giant blueberries- and though it may seem comical his attitude is scarily reminiscent of that adopted by slave-owning Americans towards their slaves or Nazis towards the inmates of the concentration camps. The book fails on many, many levels- mostly in teaching children that if you have power over someone, or that you provide them with a ‘better’ life, it gives you a license to treat them however you may wish to do so. A lesson that will not serve them well in the days to come.

(Image Credit: BBC)

HE HATES TO BE HAPPY. HE IS ONLY HAPPY WHEN HE IS GLOOMY

While critics have been kinder to one of Dahl’s earliest novels- James And The Giant Peach, it none the less met with its fair share of criticism and the author even had trouble finding a publisher in the U.K. The criticism against Dahl for James has primarily been for the racism and profanity it features. What makes this even more interesting is that despite the book trying to portray a modern and accepting view of the world, there is a lot of inherent and subtle racism through the book. The protagonist, James, befriends some overgrown insects across a variety of species and collectively they go on a fantastic journey across the Atlantic, whilst living inside of a giant peach.

When James questions his new friends about other subspecies, both the ladybird and the grasshopper aren’t the kindest to their brethren. The ladybug prides herself on being nine-spotted and generalises that all the two-spotted ladybirds are ‘common and ill-mannered’, while the five-spotted ones are ‘a trifle too saucy for (the ladybird’s) taste’. Similarly, the grasshopper says that he is a short-horned grasshopper and is rather dismissive of his long-horned cousins. My issue with this is that it subtly teaches children to judge others based on how they look and their physical characteristics, and to stereotype by asserting that all people who belong to a certain race will behave in a similar fashion to each other- ill-mannered or saucy as far as the ladybird is concerned.

The book, similar to Charlie, indulges in a fair amount of fat-shaming when it comes to the evil aunt Sponge. Starting with her name, the characters are constantly deriding her not only because she is evil but also because she is fat. Should aunt Sponge be hated because she is nasty and tortures James? Yes. Should she be poked fun at because she is fat? No.

(Image Credit: Pinterest)

HUMAN BEANS IS THE ONLY ANIMAL THAT IS KILLING THEIR OWN KIND

Maybe Dahl wanted to portray the above statement through his work, but I found a disturbing pattern throughout his works- he featured gratuitous violence. James’ parents don’t just die, but they are eaten by a rhino on the loose, and he didn’t just escape his aunts but he squashes them dead, leaving them as ‘lifeless as a couple of paper dolls cut out of a picture book.’ Similarly, the witches are turned into mice and then squashed with frying pans and decapitated with meat carving knives. And Mr. Wonka takes a certain perverse delight in the cruel punishment being meted out to the ‘nasty children’- whether them turning into giant blueberries that need juicing, or getting pushed by squirrels into giant garbage chutes and almost being incinerated.

Similar to his adult fiction, Dahl takes delight in creating macabre situations where the antagonists meet with violent ends or punishments. The danger in this is that it teaches children that if someone is ‘bad’, it is alright to exact revenge on them, and that too violently. Children’s minds are easy to influence- it is imperative for an author to be aware of what he writes and try to mould their fragile minds in the best way possible.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

It is possible in 20 years the whole world will have turned vegetarian and J.K. Rowling will be heavily criticised for featuring exotic meat-laden feasts in Harry Potter, or Julia Donaldson will be thought of as anti-animal rights because the old woman in A Squash And A Squeeze didn’t want to share her house with the farm animals. Sometimes books do not stand the test of time, and that is fine because they need to be relevant to the current audience. However, with Roald Dahl I found that it isn’t just about the test of time- his books are not the best work to be read to children, for the lessons they teach are just wrong- when he wrote them and even now. Much of the criticism against Dahl is fair.

As a young boy, Nirbhay had the annoying habit of waking up at 5 a.m. Since television was a big no-no, he had no choice but to read to entertain himself and that is how his love affair with books began. A true-blue Piscean, books paved the path to his fantasy worlds- worlds he’d often rather stay in. Nirbhay is the co-founder and publisher of The Curious Reader.

You can read his articles, here.

I grew up reading Roald Dahl too and while I used to think how dark the setting of his novels were looking back, I never looked at them in this way… However, I distinctly remember the Oompa Loompas being treated like slaves… Great post! You made me look at these novels in a totally different way!

Thank you, the novels shocked me too when I read them! It was like my childhood came crumbling down!