Feature

Why Bijji Became A Collector Of Rajasthani Oral Traditions

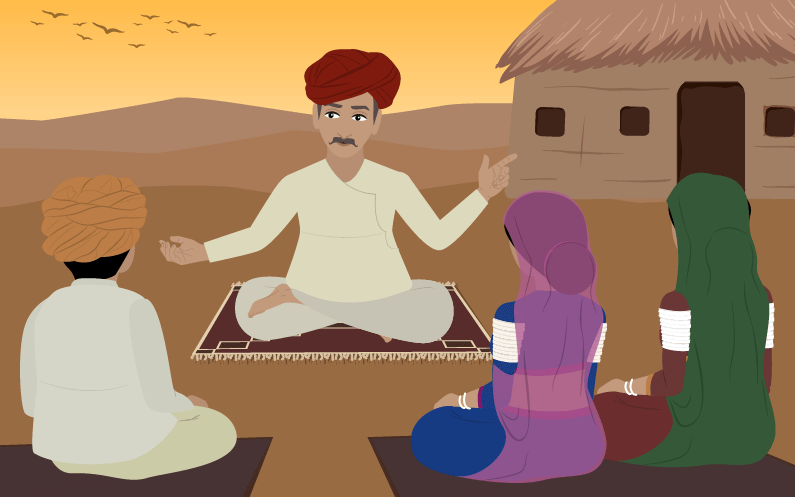

‘My village was my university, and my literary education, if any, came from rural women who always had so many interesting stories, anecdotes and wisdoms to share. When men my age went out to hunt or drink, I used to sit in my courtyard listening to what the women had to say, their gossip, their tall tales. At one point, I specifically started to invite all the women who were willing to just sit with me and talk. There were days when I was surrounded by women lost in conversations for hours at end.’

‘. . . And I began to find a respect for the exploited classes of society. There is the scent of this in every letter of my ‘Phulwari’. I was born into the Charan caste, but I have sung praises of toil and sweat and have left no stone unturned in insulting those elites who survive on the toil of others.’

—Bijji

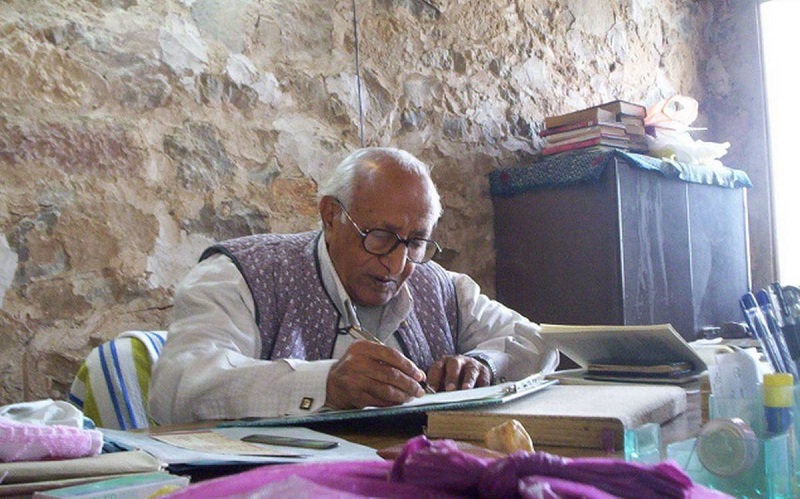

Vijaydan Detha, fondly known as Bijji, was born in 1926 into a family belonging to the Charan caste—a caste of poets and bards, often associated with courtly patronage. While Bijji continued the literary tradition of his caste, he wrote not about forts and palaces, kings and queens and their battles, but about the common folk of Marwar (in Rajasthan). However, what made his work truly unique and ahead of his time was that not only were the common folk of Marwar the subjects of his writing, but they were also where he found the source material for his work.

Bijji left Jodhpur in 1959 and returned to Borunda, his native village. Moreover, he decided that just like the literary icons of 19th century Russia chose to write in their mother tongue, he would also only write in his mother tongue, Rajasthani. This choice of language was a radical and political one.

The Rajasthani language, to this day, has no official recognition—not in the Eighth Schedule of our Constitution, and not by the state of Rajasthan. This means the language has no constitutionally protected right to be in public spaces and has no official existence, despite it being spoken by nearly 4.75 crore people as per the figures in the 2011 Linguistic Survey. The medium of education in schools and colleges, the businesses of the Vidhan Sabha, Courts and even gram panchayats in Rajasthan must be in Hindi. Bijji was a part of the movement to campaign for the recognition of Rajasthani as a language in its own right. Hence, his act of choosing a language also became an act of assertion of a distinct cultural and linguistic identity.

He also chose to work with oral traditions, realising their uniqueness and fragility.

Today, the site of learning has shifted from the home, the community, clan or village to institutions such as schools, colleges and degree programmes. In such a situation, oral traditions, which are sustained only through their continuous transmission within families, communities and clans, are at risk of disappearing altogether.

But the oral traditions that Bijji collected – who did they belong to? Whose voices were they?

(Image via The Hindu)

Consider an example. In Rajasthan, every caste has its own distinct caste of genealogists called ‘ravs’ or ‘bhats’— who maintain family genealogies for their patrons. Bhats in Rajasthan can be of two types—the pothibancha bhats, also called ‘bahi bhats’, who maintain written records of their patrons’ genealogies, and mukhbancha bhats who keep these records in oral form only. Now, interestingly, the pothibancha bhats or bahi bhats are almost exclusively patronised by the upper castes. All the lower castes have their genealogies maintained in forms that are entirely oral.

This pattern is not just restricted to history-writing. The written word is the preserve of the privileged, while all the rest have histories, memories and identities that are oral in nature. While the written word is exclusive and esoteric, the oral tradition is diverse and inclusive. Bijji realised that if he could tap into the vast reservoir of oral traditions of his land, he would be able to find literature of, about and by people whose voices are hardly represented in the body of written literature—Dalits, women, farmers, craftspeople and nomadic tribes.

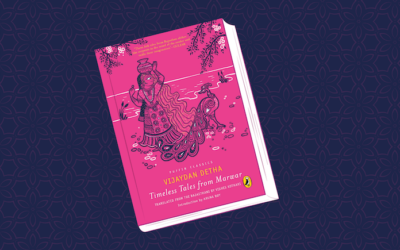

For nearly five decades he collected stories, tales, legends and lore from the people of his village—a wandering monk, old women, bards and minstrels, and cowherds and peasants. He would pay women working as daily wage labourers on farms a wage to just come and narrate stories to him day after day. And then he would craft these oral traditions into a form that was written. The result was the monumental 14-volume Bataan Ri Phulwari, a collection of folk stories. Timeless Tales From Marwar is comprised of selected, translated and retold stories from this collection.

Bijji was not interested in creating a mere archive of oral traditions by transcribing what he heard. Instead, he regarded these traditions as legitimate literature. Bijji’s belief was that he could address the most contemporary issues of our times by using this source material as inspiration. After all, these oral traditions had been passed on for so many generations and yet, they had retained their vitality and meaning. So, from homosexuality to the Emergency to gender, caste and class – the folk tale became Bijji’s political, social and cultural voice.

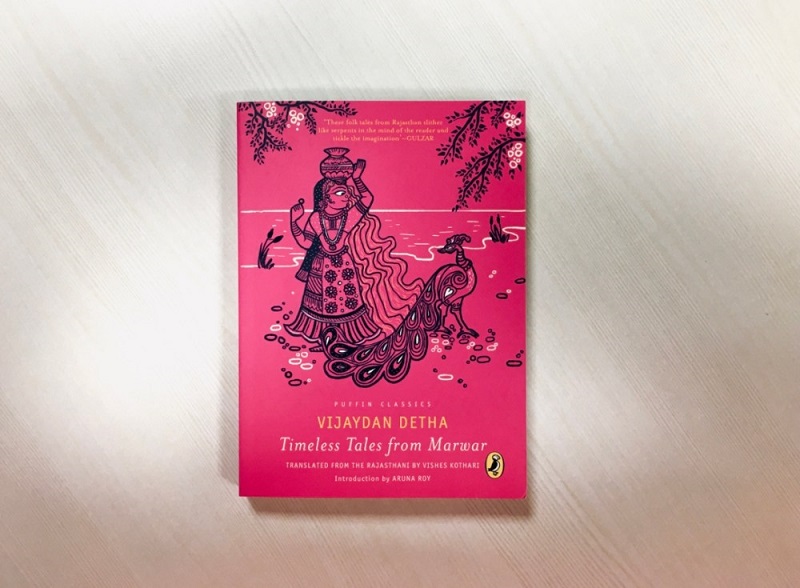

(Image via The Penguin Digest)

And thus, Bijji became a re-teller of these stories. Some of the oldest and most popular tales and legends of Rajasthan are to be found in these retellings—from the story of Jheentiya to the conversation between Raja Bhoj and the old woman. The voices to be found in these stories are refreshingly different and keep challenging our assumptions about modernity and the teleological progression of social morality. While this book is formally under the Puffin imprint, these stories would have been heard and shared by people of all ages. As Viliyo, the barber, says in one the stories in this book – ‘Each will find meaning in this as per his wisdom!’

When Viliyo says ‘each person’, perhaps he does not only mean each person, but also each generation. And that is why these tales are truly timeless.

A financial consultant by profession, Vishes Kothari completed his masters in mathematics from the University of Cambridge, prior to which he studied at St Stephen’s College, Delhi, and King’s College, London. He then taught mathematics at Ashoka University before turning to financial consulting. He is a native of Sadulpur in Rajasthan and has a keen interest in the oral and musical traditions of his state. He has been associated with UNESCO-Sahapedia on projects focussed on the musical traditions of women in Rajasthan, and as a language expert with the Jaipur Virasat Foundation. You can follow him on Facebook.

Read his posts here.