Feature

More Human Than Humans: Exploring Animals In Graphic Novels

It’s been over 30,000 years since anthropomorphic art has been an integral part of polytheistic human religion; from cats to elephants, the ancient Egyptians and Hindus sanctified deities made in the likenesses of animals they revered or feared. The Greek gods of Mt. Olympus or the Norse gods of Asgard would regularly morph into animals to intermingle with (and, less frequently, impregnate) the lesser human race, and most of the animistic New World or Polynesian religions — the pagan ones that developed independently of each other, even — featured animal gods as a central crux of their creation myths.

Fast forward to the extinction of most non-monotheistic religions and the advent of the printing press in Christendom — animals begin to dribble down into our stories and fables, through written traditions rather than oral. A few centuries later, when mass printing methods had evolved, the animals began to have stories to themselves: they dressed in human garments, had complex human inter-relationships (and complex relationships with humans) and had somehow evolved into walking upright and talking.

Today, animals and their anthropomorphism are very common in graphic narratives, whether they are intended for adults or children. On celluloid, they’ve leapt onto our theatre screens — and then televisions — with gusto, popularised by Walt Disney and his company only to become part of our collective consciousness. Their subsequent integration into the newer forms of published visual narrative — comics and graphic novels — was all but predestined, some of the best examples of the form having been written with animal protagonists.

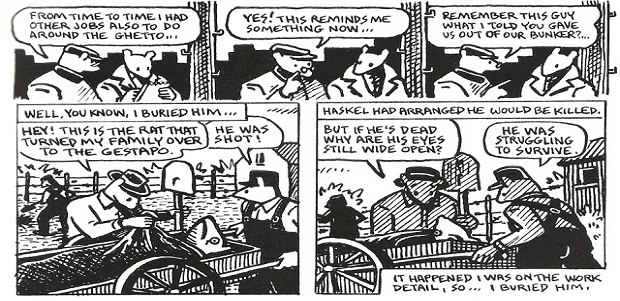

Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-winning duology Maus, a watershed publication, stresses that it’s the hierarchy of animals that’s so easy for us to digest and understand — in humans, these social ladders often have to be explained to the extent that this exploration in itself can become the narrative. In animals, however, the strata are immediately evident in a social context — mice (Jews) are the lowest mammals, then come cats (Nazis): dogs (Americans) are at the top of that particular food chain. Maus is the story of a son (Spiegelman), understanding his father’s many failings through the lens of his experiences as a Jew in a World War II concentration camp. Spiegelman uses the reader’s ability to quickly differentiate in the visual medium — these are the oppressed, these are the oppressors.

The devil’s in the details, however — Maus doesn’t merely elicit a response from the reader, it elicits the right response. After all, a human can be drawn with a range of expressions, but the micro-expressions in our features, easy enough to understand in real life, are difficult to pencil in. It’s easier to use an animal’s range of recognised habits — a swish of a cat’s tail to indicate disgust, or a horse pacing in place to show he’s restive.

In Brian K. Vaughan’s more modern, celebrated classic, Pride Of Baghdad, for instance, even in times of extreme duress, the lion rests while his lionesses hunt — the allegory of this to the overarching patriarchal themes of housewives saddled with menial jobs holds a mirror to the plight of women in third-world countries just like one the lions were captive in.

Vaughan’s heartbreaking graphic novel opens with the Americans razing Baghdad during the ’03 invasion of Iraq, bombing the city to rubble in a riotous celebration of destruction as incandescent as the yellow sun. A pride of lions escapes the famed Baghdad zoo (other animals aren’t nearly as lucky) and try to survive the bleak, deadened urban landscape beset by danger from all avenues. The symbolism is undeniable and is a strong indictment of the war itself and the effect it had on helpless, innocent civilians.

Why choose animals, though? Perhaps since, because of their consummate blamelessness, they’re a raw canvas for human emotion. It’s easier to make a point with animals than humans, who may be tragic figures but are sometimes too embroiled in personal and state politics to garner the sympathy that the writer intends. One may agree with America’s warmongering foreign policies, for instance, but the plight of a pride of lions, once majestic rulers of savannahs, reduced to scared cats, out of place and terrorised by forces beyond their comprehension, cuts across national and cultural divides to pierce the reader’s very soul.

It might also be because animal behaviour is universal, while human norms, customs and mores are not. We change constantly and, despite being more globally connected than ever, are often alien to cultures not our own. Some of human-kind might seem endearing, but biases against the ‘other’ humans, whoever they may be, are a part of us all.

(Panel from MAUS via ineedartandcoffee)

Sometimes, the use of animals as protagonists can bring a fresh, humorous take on overdone tropes and archetypical plotlines. In Evan Dorkin’s comic series, Beasts Of Burden, he does precisely this — borrowing stereotypes ranging from Enid Blyton’s Secret Seven and Famous Five to the Hardy Boys, he flings pets and supernatural happenings into the mix to create stories of neighbourhood investigations that are solved by canine warlocks (and a cat) and feature werewolves, golems, and zombie roadkill. In a completely inventive take on the genre, Dorkin turns teen mysteries on their head and finds depth in the protagonists’ obviously animal lives (the Doberman’s owner is a drunk who ‘won’t miss him’ when he’s out adventuring, and one of the stories centres around a lost dog whose family moves away) while dealing with paranormal horrors of human myth and making (a coven of witches, a rain of frogs, summoned spirit animals).

It’s also that, with animals, we tend to focus on the micro-tragedies rather than macro-. It’s easier, therefore, to appeal to our humanity. In the painstakingly drawn Munnu: A Boy From Kashmir (by far the best Indian graphic novel that this writer, personally, has read to date) Malik Sajad presents the Kashmiris, in Spiegelmanian form, as the critically endangered Hangul deer (or Kashmiri stag).

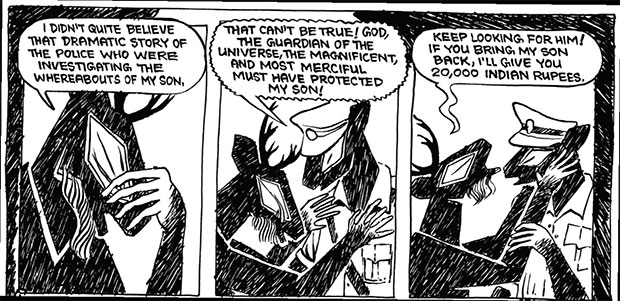

In a Sacco-esque graphic novel that deserves a contemporary re-reading with regards to the current state of affairs, Sajad’s semi-autobiographical account of his childhood and teenage years in the war-riddled (now former) state of Jammu & Kashmir illustrates, in brutal detail, how the clash between India and Pakistan’s Islamic pull renders civilian life nigh impossible. A war that is so far and only revealed to us in bits and pieces on nationalistic television news channels comes alive as a very real conflict that makes casualties of flesh and mind with equal abandon. In his own journey into a prodigal political cartoonist from a destitute family, Sajad finds poignant poetry in the minutiae of a Kashmiri Muslim’s joys (few) and sorrows (many). Perhaps it’s best that the characters in Munnu remain deer — were they human, politically attuned right-wing sympathisers may not wish to comprehend the nuance and flow of the atrocities inflicted upon this region or the jingoistic fervour with which many in the country justify them.

(Panel from Munnu: A Boy From Kashmir via Tehelka)

Simplifying these arguments by shunting them into logical compartments is one thing, but in reality, the historical and social aspects that have made animals such a significant part of comic and graphic novel traditions are more than the sum of these simplified parts. To wit: it’s not just an animal’s ignorance of the outside world that allows the creator to explore known atmospheres in a new light, or their constant presence in human lives in ways that so often prick our conscience — it’s also the intensity of reactions and emotions that can be portrayed (some of which would look far too out of place in inked humans), and our species’ subconscious longing to right the wrongs we’ve inflicted upon their world. It’s a complex web of factors that has made the animal kingdom a go-to source of inspiration for such a multitude of graphic narratives, fitting them into genres ranging from horror to sci-fi and from drama to flat-out comedy.

In the course of my research, flitting between academic journals that pinpoint the science behind our attraction to anthropomorphic beasts, and interviews with novelists themselves explaining the allegories within their work, it’s become apparent to me that animals are more easily given to a visual form of storytelling than the written word — as much as Redwall and Watership Down are classics of children’s literature, the visceral connection of reader to page, watching an animal’s emotional spectrum unfold in ink, is still a deep-rooted cause for childlike wonder, centuries after humans first drew them. After all, these animals are our personal windows into the alien magic of the natural world.

Tej Haldule is a writer who currently lives in Goa.

Read his articles here.