Feature

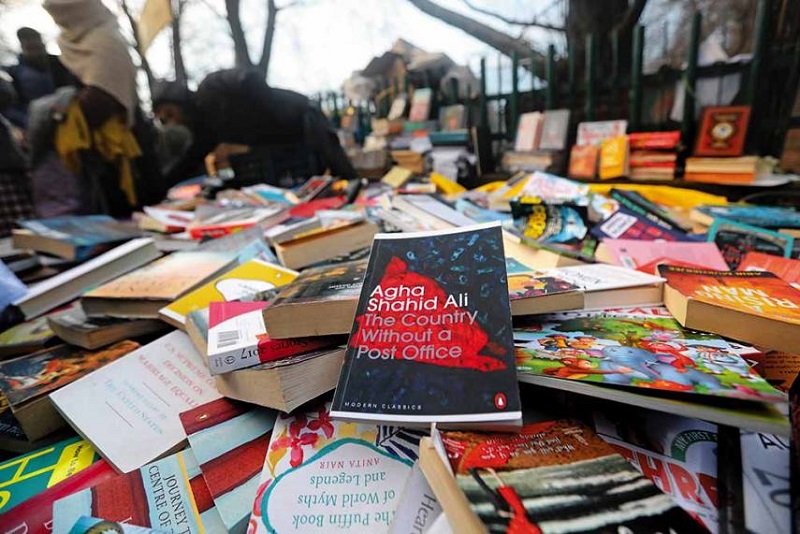

Why You Must Read Agha Shahid Ali In 2020

In the light of poems being misconstrued or taken out of context in recent times as well as using unnecessary rhetorical arguments to shut down dissent, it is important to examine the role of poetry in portraying conflicts and speaking out against injustice.

Agha Shahid Ali’s poetry does exactly that.

Ali wrote widely on Kashmir (his home), and his self-imposed exile and homelessness during his time as a student in America. He stayed on in the U.S.A. as the condition deteriorated in Kashmir in the late ’80s and early ’90s. He did visit his parents in Srinagar over summers in the ’80s and was thus ‘an intermittent but first-hand witness to the mounting violence that seized the region from the late 1980s onward’. Ali experimented with the ghazal style in his poems and is known for having popularised the form among American poets.

The Country Without A Post Office (1997) became one of his most well-known poetry collections, encompassing several facets of Kashmir’s destruction in the 1990s. The poems in this collection portray a Kashmir ravaged by terrorism, but go beyond statistics to show the impact of the rise of militancy on individual lives, the state’s culture, and on Ali himself.

Ali’s Poetry As Political

Though Ali’s poems take no political sides, they are political in the way they take the side of humanity in condemning all forms of violence that wrecked Kashmir during the ’90s. This condemnation comes in the form of invoking a Kashmir from a bygone era when unity reigned and not terror, or in recalling a deep sense of Kashmiriyat that previously united the people. It is these invocations that suffuse Ali’s poems with his trademark melancholic tint.

The condemnation also comes by acknowledging the violence and its repercussions on both Kashmiri communities. For example, in the poem, ‘Farewell’, from The Country Without, the narrator (presumably Ali himself) addresses a Kashmiri Pandit friend, stating:

At a certain point I lost track of you.

You needed me. You needed to perfect me.

In your absence you polished me into the Enemy.

Your history gets in the way of my memory.

I am everything you lost. You can’t forgive me.

I am everything you lost. Your perfect Enemy.

Your memory gets in the way of my memory.

These lines depict the subsequent and almost inevitable hate that follows terrorist attacks – hate that is used to further pit one community against the other. Yet Ali manages to pre-empt this hate. He realises that the two communities will now view each other with mistrust, turning the other into an ‘enemy’, even though they used to coexist harmoniously earlier:

In the lake the arms of temples and mosques are locked in each other’s reflections.

And, it is because he anticipates this hate that Ali quietly emphasises on peace at the end of his poem, despite knowing it to be a difficult prospect:

There is everything to forgive. You can’t forgive me.

If only somehow you could have been mine,

what would not have been possible in the world?

The poem, thus, as Claire Chambers mentions in her essay, ‘The Last Saffron: Agha Shahid Ali’s Kashmir’, is ‘about the ‘othering’ of the two sides in the Kashmiri conflict’.

(Image via Outlook India)

The Relevance Of Ali’s Poems Today

Though his poems speak of a time over 20 years in the past, many of the themes embedded in them are still relevant when one examines the politically oppressive manner in which Kashmir has been handled. ‘Farewell’ bids a mournful goodbye to Kashmir’s former peace, while finding relevance today in the ongoing religious and political polarisation of communities.

While the Internet did not exist in the ’90s, Ali’s poems talk about a different clampdown of communication when telephone lines and post offices were shut leading to countless unsent letters and postcards. In ‘The Floating Post Office’, from The Country Without, Ali portrays a city enveloped in a ‘fog of death, the sentence/ passed on our city’, where the roads are closed but the canals still function. Hope comes in the form of one quaint floating post office as it delivers letters; words that let people know their loved ones are alive. The waterways, thus, become vital for everyone’s survival, with the postman on the gondola holding on to the letters ‘like a lover, close/ to his heart’.

The titular poem from The Country Without also conveys the desolation and devastation of a land where no letters are being delivered:

archive for letters with doomed

addresses, each house buried or empty.

Empty? Because so many fled, ran away,

and became refugees there, in the plains

In the poem, a solitary figure is wandering the city’s streets and taking in the destruction. In an attempt to understand the havoc, he reads these letters and answers them:

I read them, letters of lovers, the mad ones,

and mine to him from whom no answers came.

I light lamps, send my answers, Calls to Prayer

to deaf worlds across continents. And my lament

is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

to this world whose end was near, always near.

My words go out in huge packages of rain,

go there, to addresses, across the oceans.

It’s raining as I write this. I have no prayer.

It’s just a shout, held in, It’s Us!

It’s Us! whose letters are cries that break like bodies

in prisons.

One can’t help but interpret his answering of the letters as a cry for help to the outside world from which they are now cut off. It is his way of reminding the world that they exist. The letters are cries of anguish, cries of wanting to be recognised, remembered and treated fairly. Though written in 1997, the poem is almost prophetic, mimicking the ongoing communication clampdown in Kashmir where it is, once again, cut off from the rest of the country. It has, very literally, become a country without a post office.

Another pertinent poem from The Country Without that comments on the centralised decision-making process for Kashmir is ‘Muharram In Srinagar, 1992’. The opening and closing lines are similar, and succinctly use the metaphor of a bureaucrat from the plains bringing in death and pain to the region.

Ali describes the bureaucrat’s efficiency and the bubble he lives in:

He travels first class, sipping champagne…

He descends. The colonels salute. A captain starts the jeep.

The Mansion by the lake awaits him with roses….

The Mansion is white, lit up with roses.

He then juxtaposes this rosy picture with the horrors of death in the valley:

In the Vale the children are dead, or asleep…

He’s driven

through streets bereft of children: they are dead, not asleep,

O, when will our hands return, if only broken?

This contrast is telling, especially today, when politicians sitting far away decide on the fate of a region, without taking a deeper look at the consequences of their decisions.

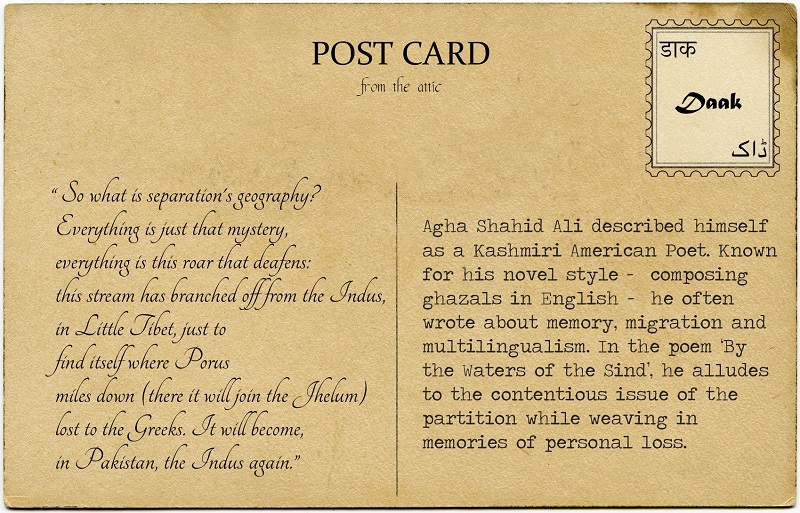

(Image via Daak)

While Ali did write from a distance about his homeland, his words still carry an unbearable sense of loss and suffering that he felt and witnessed on his visits home. He used his words as a medium of resistance and to question the insensible violence wrecking his homeland.

This grief for his home and his role as a poet are beautifully voiced in the closing lines of ‘After The August Wedding In Lahore, Pakistan’ from The Country Without:

The century is ending. It is pain

from which love departs into all new pain:

Freedom’s terrible thirst, flooding Kashmir,

is bringing love to its tormented glass.

Stranger, who will inherit the last night

of the past? Of what shall I not sing, and sing?

We are now well into the new century, and recently celebrated the beginning of a new decade. And, it is time to pause and read Ali’s poems to remind ourselves to not fall prey to one-sided arguments that solely peddle hatred and hypocrisy. It is important to read his poems to understand the Kashmir conflict on a humane level and to know that love and friendship triumphs extremism and animosity.

Like many other bookworms, Aakanksha Singh dreams of owning a cosy library and having the privilege of reading books all day! She enjoys immersing herself in a book, exploring worlds through vicarious travel, being one with the character, discovering words and admiring a singular turn of a phrase while trying to commit it to memory. She blogs at The Book Café and shares literary tidbits on her Facebook page, The Kitab Sherni (as she imagines herself not as a book dragon but as a bookish lioness).

You can read her posts here.