Excerpt

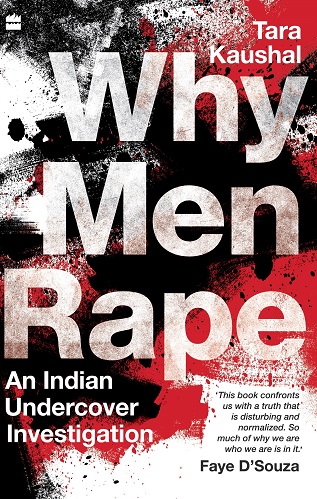

Why Men Rape

There is no doubt that the sexual abuse Chandran had experienced had played a part in this lifelong emotional turbulence.

When Chandran was four or five, the full-time help his working parents employed went on a weeklong holiday, and had left a stand-in. She must’ve been eighteen or nineteen at the time, a dusky woman with long hair who wore blouses and flared skirts. After school in the afternoons, the maid would put his younger sister to sleep, and then take him to another room where she would sexually abuse him, using the promise of gifts to buy his obedience. “No penetration, but all of the rest happened.”

***

Yes, women rape; yes, men and boys are raped. Another fallout of the female-as-weak, male-as-strong binary is that women aren’t seen as sexual initiators and potential perpetrators of abuse; boys aren’t seen as needing protection and care. This extends to pubescent boys abused by older women, as a relative of mine was by his teacher. When he told his friends about his “relationship”, he was met by backslapping and hearty congratulations—if he had been a girl and she a man, it would’ve been seen as the child sexual abuse (CSA) by a predator that it was. This is reflective of the cultural narrative that men and boys are sexual seekers while women are gatekeepers; and the romanticizing, fetishizing of the Savita Bhabhi trope, where an older, experienced woman initiates boys into manhood as a rite of passage. This is a dangerous way in which to frame sexuality.

“She was feeling good about it. Moaning.” And so was Chandran—“I thought it was a pleasurable thing to have sex because I had experienced it through my abuse”—a reaction that would lead to confusion and guilt in later years. “I lost my childhood then.”

When the permanent maid returned, Chandran told her what had been happening, mainly to complain that the promised gifts never came, and she told the parents. There was a confrontation of sorts and the replacement maid was dismissed. Chandran never saw her again. What seems bizarre but was apparently normal, even among educated people, his parents never spoke to him about sex or sexual abuse, even after they knew what he had been through. (This was thirty-five years before; sex education and the awareness of the sexual abuse of male children has increased in this social class.)

***

It is a widespread belief that people who were sexually abused in childhood often participate in abusive relationships as adults—either as victimizers of children and adults, or as victims. Some people call this a dangerous myth, which can be used to explain or excuse the behaviour of those who sexually abuse children. It is offensive and unhelpful to demonize adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse, the vast majority of who will never perpetrate sexual violence against others. There is, however, some empirical evidence for belief in this ‘cycle’, and the results of the few studies that explore this issue support this hypothesis. In an incisive study called ‘Cycle of Child Sexual Abuse: Links Between Being a Victim and Becoming a Perpetrator’, the authors found that, among 747 men studied, “the risk of being a perpetrator was positively correlated with reported sexual abuse victim experiences. The overall rate of having been a victim was 35 per cent for perpetrators and 11 per cent for non-perpetrators. A high percentage of male subjects abused in childhood by a female relative became perpetrators. Having been a victim was a strong predictor of becoming a perpetrator…” Other studies on sexually abused boys have shown that around one in five continue in later life to molest children themselves.

This stands to reason. If physical violence violates a child’s rights and autonomy, CSA and incest is infinitely worse for the layers of psychological scarring. In ‘The Cycle of Sexual Abuse and Abusive Adult Relationships’, the noted psychologist Elizabeth Hartney proposes some of the reasons why victims become victimizers. In an attempt to heal, and reclaim power and control, they take the opposite, seemingly more powerful, position of abuser. Or they feel grandiose to counteract the feelings of inadequacy, strange though it may seem, and, therefore, “may have a hard time respecting other people as equals.” They may be sexually aroused by abusive behaviour and the intensity of emotions evoked by forbidden contact.

***

Having said that, an idea that has stayed with me for a long time (the origin of which eludes me) is that, for those who live an examined life, childhood experiences serve as a pivot. To illustrate—the child of an alcoholic can be an alcoholic, claiming nurture or even nature; or a teetotaller, having seen the havoc the parent’s habit wreaked. In this vein, Chandran positioned himself as a modern, woke, global Indian; against the stereotype of the patriarchal and violent Indian man that his father represented. He loved his mother, who had worked all her life; his sister, friends and girlfriends were independent workingwomen too. “There are very few things, that we know of, that have such a clear effect on gender inequality as being raised by a working mother,” summarizes Kathleen McGinn of the Harvard Business School, who led a ten-year study on the subject. As a survivor of abuse, Chandran had all the right answers, made all the right noises. And yet…

In a macro sense, Chandran and I are part of the same social circles of arty liberal upper-class Indians. Evenings out in Bengaluru, to house parties, gigs and events, are of the fluid, hopping variety so familiar to us in Mumbai and Delhi. You arrive with friends and/or a date. As expected, you meet others you know there. You get high. Some drift off for one place or after party or another. You get higher. Repeat. Hook up. Until you’re too high or it’s seven/eight/nine a.m., whichever comes first (or you decide to proceed to breakfast). You go home or crash at a friend’s. It was on one such drunken night, six-odd years prior, when a young woman—a platonic friend; a former colleague from a content creation company where he had, typically, worked for a flash—and another man had ended up in Chandran’s house, where they all slept in different rooms. She had woken up to find herself naked, his tongue in her vagina.

Note: This is an edited excerpt.

Tara Kaushal is a writer and media consultant. She was recognized for her incisive journalism and social commentary and was awarded The Laadli Media Award for gender-sensitive writing in 2013-14. In 2018, she was awarded Femina Women Super Achiever Award. As the growing conversation about sexual violence is getting more meaningful and nuanced, Kaushal is one of the voices at its forefront in India.

Excerpted with permission from Why Men Rape, Tara Kaushal, Harper Collins, available online and at your nearest bookstore.

Thank you for sharing this excerpt.

I had read that victims of CSA have a higher likelihood of becoming perpetrators themselves; I had also read about males being raped — by males and by females. But I hadn’t put the two ideas together. I hadn’t realised that boys being abused by women was so prevalent.

I have long found it odd that women are automatically assumed to be fit to look after children; whereas a man’s closeness to unrelated children (e.g. as a nanny, step-parent, stranger on the street, or preschool teacher) equally automatically leads to suspicions about his motives. This is silly — not all women are nurturing, whereas many men do have caring attitudes to young children. Sexism never produces good outcomes — whether it’s against men or against women, whether it’s ‘benevolent’ sexism…

From this brief excerpt, it seems clear that this book has a scientific attitude to data analysis. E.g. you write that there is *some* truth to the myth about the vicious cycle of NSA, i.e. perpetrators are likelier than non-perpetrators to have been CSA victims themselves. That sort of nuanced approach is necessary when we’re dealing with a sensitive topic — or really, anytime we’re trying to quantufy data in order decide whether or not A is related to B.

Thank you for tackling this issue. This book addresses a question we’ve all had. I’m sure your insights will make us uncomfortable. But discomfort is the first step to change.

Anita, thank you so much for your lovely comment. It made my day. 🙂 My approach throughout this book is to take all the data—the studies, the books, the theories—and see how they intersected with my subjects’ narratives. I hope you’ll enjoy reading it!