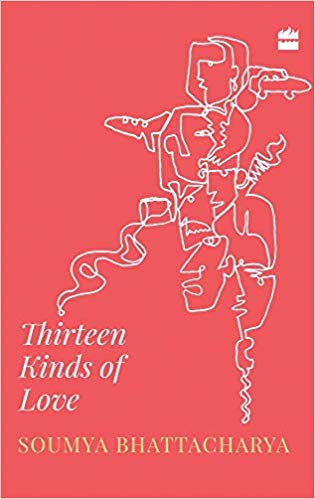

Excerpt

Thirteen Kinds Of Love

Some weeks ago, Ajit Dandekar’s son had asked him: ‘Dad, do you feel awful when you have to let yourself into the flat and it’s dark and you have to switch the lights on yourself?’ Ajit pretended to study the label on a bottle of diet mayonnaise. ‘Hmm. Mmm?’ He knew what Sachin wanted to hear. He knew that he would have to be careful about how he phrased his reply.

‘Dad, do you feel awful if you have to let yourself into the flat and it’s dark and you have to switch the lights on yourself?’ the seven-year-old asked again, his tone ascending in pitch, insistence braided into the question mark at the end of the sentence.

‘Well, I used to live on my own for years, Sach. So I don’t particularly mind. But all that was before you were born. Now it feels odd when I come home and you aren’t here. But that doesn’t happen very often, does it? Yeah, I would much rather have you at home when I return. It makes me happy.’

‘That’s not a proper answer, Dad.’

No, it wasn’t, and Ajit knew. He had disappointed his boy. But he hadn’t been able to come up with a more unequivocal way of framing his response. The answer actually was yes and no; but it would have been disastrous to have said so. More often than not, Ajit came home before his wife. The boy was on his own till then. Of course Ajit loved to have his son fling himself at him as soon as he opened the front door. Of course he loved the lights on, the books strewn on the table, the smell of food from the kitchen, and the anecdotes from his day at school.

But sometimes, just sometimes, he liked the quiet order and stillness of returning to an empty apartment; the sense of control and space that the uninhabited state of the apartment afforded; the amplified sound of the switches being flicked on, the light swallowing the incumbent darkness, the freedom to sit where he liked for a few moments in silence, to kick off his shoes and put them back in the closet after a while, to fling his clothes on to the bed and watch TV with the volume turned right up. (You don’t do those things when your little son is around; setting a good example becomes a cornerstone of the responsible father’s life.)

Ajit’s wife, Priyanka, worked in the human resources department of a large conglomerate. She kept inhuman hours. Her colleagues called her at any time they felt they needed her help, at any time at all they wanted things sorted out. On occasion, they would call Priyanka from New York or Los Angeles (cities the senior staff of the company frequently visited) when it was afternoon in the US. It would be well past midnight in Bombay by then. Priyanka never switched off her mobile phone; her job was such that she could never even afford to turn it silent.

Ajit wondered how she managed. But she managed all right, instilling a sense of calm and order at home, distilled from the chaos of the workplace. She had texted him this afternoon, saying that he needn’t bother, she had nipped out at lunchtime and bought the ball of wool, felt-tipped pens and whatever else – he couldn’t even remember, now – that Sachin needed for a project in school. ‘Without you …’ he had texted her back. No, Ajit would never be able to do without Priyanka. He would never be able to do what Priyanka did for the family. He got too wound up about things at work, felt too much on edge, too annoyed too often; and the frustration born of anger often got the better of him.

On days when that happened, Ajit didn’t mind – no, he actually enjoyed – returning to a dark and empty flat. On days such as today. It had been dreadful in the office. He didn’t want to think of it or tell his wife about it. Without Priyanka and Sachin around, he would be able to collect himself and put the rancour of the day behind him. At least for tonight. He would tell her about it tomorrow evening, perhaps. They would not be able to laugh about it (he was never able to laugh about these things), but at least he would be up to talking about it. For the moment, Ajit wanted to not have to talk any more, to not talk to anyone for a while. He wanted to sit in his leather armchair, in front of the 64-inch TV and have a quiet drink or two. Or three. Or four.

Priyanka worried about what Ajit had to deal with at his office, the hostility that he often had to face. She had made him – essentially a sedentary man with a fondness for sweets and red meat – join a gym a year ago. Ajit had taken surprisingly well to the regime of daily cardio and light, and then heavy, weights. And once his fat began to burn away, the contours of his muscles began to get pronounced, he delighted in wearing T-shirts that were a size too small for him; for the first time in the eleven years that they had been married, Priyanka saw him unselfconsciously emerge from the shower with only a towel draped around his waist. Priyanka encouraged what had now become her husband’s gym addiction. At the same time, she could not keep herself from worrying. You couldn’t be too careful. Forty-one was a risky age. And there was nothing one could do about the stress he encountered and the manner in which he responded to it. She knew, she was in HR. Only last year, a perfectly healthy colleague …

Say what you will about their jobs, but between them, the money was generous. It paid for their lavish annual holidays abroad; the fees of the elite private school to which Sachin went; the tennis lessons; the black Audi, the silver Toyota and the two drivers; and their home in Imperial Heights in Bandra, constructed by knocking down the wall between the flats 9A and 9B. Now known as merely 9B, this flat had four bedrooms, a 600-squarefoot living room … Ajit loved having acquaintances over so he could show them where he lived, and how. It defined him in a way little else did.

But on a day such as today, he found that the manifestations of his hard-earned affluence did not make up for the ordeals that his job inflicted on him at times. Ajit was a marketer, the vice president of marketing in one of the country’s largest newspapers. And he could not bear the editors with whom he had to work to promote and market what he called the product and they – with dour insistence – called the paper. They were contemptuous of the way he spoke and wrote emails (‘Did they teach you about split infinitives in management school?’). They were dismissive when he suggested ideas for what could be done in the paper. And they lost no opportunity to let him know that, to them, he and all the marketing guys in his department were interlopers, mere fickle professionals who could be marketing a newspaper today and detergent tomorrow. The suggestion of course, was that they – the journalists – were unsullied by such promiscuousness and were devoted to only the media.

Soumya Bhattacharya is the author of five previous books of fiction, non-fiction and memoir. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, the Independent, the Sydney Morning Herald and Granta, among others. He is the managing editor at Hindustan Times and lives in New Delhi.

Excerpted with permission from Thirteen Kinds Of Love, Soumya Bhattacharya, HarperCollins, available online and at your nearest bookstore.