Excerpt

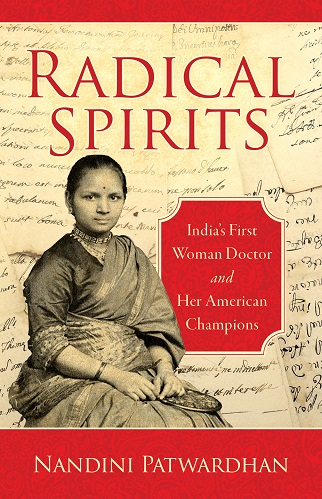

Radical Spirits

When he found Rev. Goheen’s letter in his morning mail, Rev. Wilder opened it eagerly. He breathed in the scent the letter carried—for a moment he was back in the dusty alleys of Kolapore. Goheen had written about a quite unusual Brahmin, Gopal Joshee, whose acquaintance he had made. The man was passionate about educating his wife and, in that quest, was willing to incur the wrath of his community. Goheen had never met a man who was as passionate and as unafraid of what others might say.

Goheen felt that the Joshees deserved help. More importantly, he believed that by helping them, the mission of bringing as many souls as possible to Christ would be advanced. Goheen hoped that Gopal Joshee would feel sufficiently indebted and obliged to return the favor. Indeed, he might be so moved by the power of the Christian faith to act with charity and compassion that he might willingly accept Christ and work to convince others to do the same. Goheen thought that this would be a win-win for all involved. He urged Wilder to consider helping Joshee’s wife travel to America to be educated.

Wilder felt heartened to note the tone of deference in Goheen’s letter. He may have become old and infirm, but he still commanded respect. He agreed with Goheen’s reservations about how the couple would fare in America without any support or assurances. He set the letter aside and sat back in his chair, allowing his mind to meander across the jumble of emotions he was feeling.

He pictured the Kolapore parsonage with its little garden and the church next door. He thought of his loyal servant who was ever grateful because he was treated more kindly at the mission than by his fellow Indians, especially the Brahmins. How nice it would be to have the young couple from India here in America! He imagined conversations in Marathi, discussions about Indian history and British affairs. He imagined introducing them to the curious and generous Americans, and he thought of how much easier it would be to raise funds with this couple by his side. His wife had been feeling homesick for India since their return. He knew her excitement would know no bounds at the prospect of long-term guests from India. “Like the mountain coming to Mohammed,” Wilder chuckled to himself.

He turned to the other letter, the one written by the Indian. The author used the peculiar idiom of the English-educated “native”—formal and somewhat subservient. The letter conveyed all the coordinates of the man’s social standing: his religion and caste, place of birth, and father’s name. Wilder understood that it was a way of establishing his credentials as well as his high station in the rigid caste hierarchy. He was impressed by the man’s articulateness. “My education, though very poor, has caused me to suffer rather than enjoy.” Having been a teacher in India, Wilder knew the leaps of personal growth needed to progress from basic literacy to this level of critical thought and expression. He read on:

Ever since I began to think independently for myself, female education has been my favorite subject. I keenly felt the growing want of it to raise the nation to eminence among civilized countries. It is the source of happiness in a family. As every reform must begin at home, I considered it my duty to give my wife a thorough education, that she might be able to impart it to her country-sisters, but customs and manners and caste prejudices have been a strong barrier to my views being prosecuted. Besides, our attempts have been regarded with suspicion by foreigners. On the other hand, female education is much looked down upon among all Brahmins, the highest class of people in India. My attempts have been frustrated, my object universally condemned by my own people. I have difficulties to encounter and no hopes to entertain in India, and yet I cannot give up the point. I will try to the last, there being nothing so important as female education for our elevation morally and spiritually.

Wilder felt overwhelmed by the Brahmin’s zeal. The man’s goals—uplift of family, community, and country—seemed too lofty to be mastered in a single lifetime. A lone crusader with few resources, the man was willing to risk all and start with the baby step of educating one woman—his wife. “He has the missionary impulse,” Wilder thought to himself as he put both letters aside. He would seriously consider helping the Indian couple in their quest.

Wilder had never come across an Indian, let alone a Brahmin, who so energetically berated his own community. Neither had he come across many who had a pan-Indian view of their country; most were still too mired in identities defined by their caste, language, and religion. However, he had come to know a few educated Indian men and so knew that they had the potential to become a most powerful force. He noted the parallels to the American colonists’ desire for independence from Britain, “… the old problem of 1776 is again looming up, and demanding the attention of British statesmen. Educated Hindus are petitioning for representation in the British Parliament.” He was reminded of the impatience of one of his students for the British to recognize Indians’ “growing intelligence” and for Indians to “rise to equality with the natives of England.”

Therefore, Wilder sympathized with Gopal Joshee’s passionate desire for progress and equality. However, he felt conflicted about offering material assistance. Although he could foresee the inevitability of change and the Indians’ push and capacity for it, he had also personally experienced the Hindu traditionalists’ staunch opposition to changing the status of Indian women even slightly. He was skeptical about the extent to which an educated Indian woman would be able to change, or even begin to change, her community.

He reread the letter, savoring the words on the page, trying to imagine a man clothed in the traditional flowing white dhoti, and with the shendi tuft at the top of his shaved head. As for the wife, he could imagine only a shy girl-woman laden with jewelry and wrapped in yards of sari, one who would stare at the floor making no eye-contact, speaking only when spoken to, mumbling her responses in a hushed shaking voice, and fleeing to the inner sanctum at the earliest opportunity. Surely the missionaries were more than equipped to provide whatever “education” this little woman was capable of receiving.

Even if the couple were to come to America, he continued to ponder, would they be able cope with the harsh winters? What would they eat? Their spices and vegetables, yogurt and ghee, and rice and lentils would simply not be available here.

Then there was the issue of race. It was one thing for someone like him—educated, thoughtful, and a true disciple of Christ—to go and live among heathens. It was quite another—isolating at best and dangerous at worst—for black non-Christians (Indians were considered black at the time) to live among Americans. Sure, some Americans would be warm and welcoming. But many others might see them as akin to the recently emancipated slaves and might reject them. The most extreme were likely to resort to taunting, or even violence, to make them leave.

The most important consideration, however, was the issue of Gopal Joshee’s willingness to accept Christ. Even though Goheen saw reason to hope for a high-profile conversion, Wilder was skeptical. He could well imagine that Joshee would readily accept help to attain his goal of educating his wife and yet, feeling no obligation to convert, would also resist attempts to make him forsake his gods and idols and accept Christ.

The more Wilder thought about it, the more he felt that as much as he would enjoy the Joshees’ company in America—it would be like having Little India right in his backyard—helping them come to America would be an ill-advised move.

In his response, he commended Gopal Joshee for valuing female education and assured him that more American missionaries were on the way: “Your dear wife will have a good opportunity to prosecute her studies there,” he wrote. And, being a passionate missionary, he closed his letter by urging Gopal to “confess Christ as your Savior.”

Nandini Patwardhan possesses a Masters degree in Mathematics from IIT Mumbai. She lives in the United States. Her biography of Dr. Anandi-bai Joshee, titled “Radical Spirits,” will be published in January 2020.

Excerpted with permission from Radical Spirits, Nandini Patwardhan, Story Artisan Press, available online and at your nearest bookstore.