Excerpt

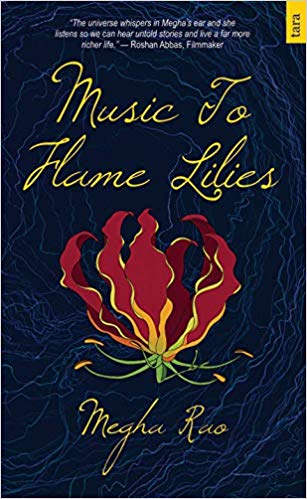

Music To Flame Lilies

We’re bantering by the time we reach our destination, and it’s a good kind of banter. Light hearted. Like Persia fairy floss. Melting inside open mouths. Tasting of saccharine. Spreading sweetness all over your insides, with the slightest of bitter aftertaste. Steaming up like a Turkish bath. Gummed to the tummy with butterflies. The three winged kind. The colour of feathers. The best kind, when one doesn’t have to define this banter. When one doesn’t have to put a name to this friendship, or whatever it is.

You’d love the libraries in England, I tell him. I wish I could bring them to you.

He’s all smiles. ‘You’re the sweetest thing, Noor. But all that is just not for me.’

‘No, really. For someone who reads as much as you do, I can imagine how wonderful it would feel. Who is your favourite writer?’

His answer is immediate. ‘Bukowski. Dostoyevsky. Maybe Margaret Atwood.’

I’m riveted now. ‘You like Margaret Atwood? What do you like?’

‘I really liked The Handmaid’s Tale.’

‘Hmm.’ I am smiling now. At last, we have similar interests. No more Chinese philosophers and women bashing writers. He has been swayed by a feminist. ‘Do you think that’ll happen to women? Will we lose control over our bodies one day? It’s possible, isn’t it?’

I expect him to burst out laughing, but he is only smiling at me adorably. I want to tell him to stop, that it’s making my insides feel so light.

‘Anything is possible,’ he says. ‘Not just to women, but to all of mankind. We are a dying race.’

‘Oh, come on. Don’t say that. That’s very pessimistic.’

‘We have already lost control of our minds. How long before we lose control over our bodies too?’

‘I liked The Handmaid’s Tale. It was very insightful.’

‘Yes, it was,’ he says, and there it ends.

Yes, it was, I think. I don’t know what to say next, but for the first time, I’m not panicking for the lack of conversation. I’m comfortable sharing words with him, and even more comfortable sharing silence with him.

I look at him, striding by my side towards nowhere, and accept that maybe it’s okay to fall. Why not, if the falling is this easy? Or maybe he’s just playing some ridiculous magic trick on me, who knows.

All at once, there are fireflies around us again. I look up. This time, I’m the one with the halo.

He turns to me and smiles.

*

Twilight meanders into the air as we sit on the plastic chairs the organizers have arranged for us. There aren’t many people here except for a few school kids and the two of us. I rest my head on his shoulder, testing him, but he doesn’t move. My mouth is dry, filled with the loss of unsaid words, but I can’t believe I’m watching a native performance and that this is my first real date with him. In London, I would have been asked out for a nice movie. We’d have hot chocolate and marshmallows, and then sit by the fireplace. But this is not London, this is Herga, and we are watching a splendid yakshagana, and today I wouldn’t have wanted to watch this with anyone else. I’m so greedy for this moment, I can’t imagine sharing it with anyone else, not even Kirti. The bhagawata begins directing the himmela, and they sing in unison. Bold, clear goldenrod and canary. I taste bitter lemon and sun glow at the base of my throat, I feel like singing and rejoicing with them. Why does everything in this village provoke my emotions so well? I look at him from the corner of my eye. This is a man who belongs to the night. Moonlight devours his face with its splash.Light touches upon his cheek like a sable paintbrush focusing on detail. I see

the kohl clearly. It is smudged and smoky and I am so fascinated I just want to touch him. Man of wolves. And I still do not know who he is.

The yakshagana goes on for some time. The pungi, maddale and harmonium float on the most enriching of ragas. My heart is honeyed. I have never listened to anything so lovely. And the drums bring the Tenkutittu actors to life. I have never seen so much sincerity and unity in song and dance.

‘I like this,’ I exclaim. ‘All the dance forms and folk art I’ve seen are always related to some story in a religious text.’ I shrug. ‘It’s all so beautiful, but I wish people were a little less fanatic about it. It feels like indoctrination at times.’

And yet again, I’m so curious to know what he thinks about all this. So I ask, ‘Do you believe in it?’

He shakes his head.

Do you not follow any religion then? I ask him again.

I was labeled a Hindu, he admits grudgingly.

‘But you’re not?’

‘I don’t think I’m one for religions,’ he comments. ‘I don’t know about god, but religion sucks the life out of people. All these great books that we’ve written in the name of religion, the Bible, the Ramayana, whatever. Do they teach us feminism? Do they teach us empathy? And respect towards each other? Why did we start the evil tradition of sati? Because one of our goddesses jumped into a pyre? Where was feminism when Draupadi was disrobed or Sita was banished without any fault of hers?

Where was feminism when Eve was being blamed for everything gone wrong in Eden? Where was justice when Persephone was abducted or when the Bible doles out instructions for slave masters and condemns homosexuality? Or maybe it doesn’t. Maybe I’m wrong and maybe we’ve all interpreted it wrong. But there is no point holding up a religious text as holy when none of its tenets are being followed. It’s all pretty on paper. By the end of the day, what matters is how well humans have imbibed goodness into them. It doesn’t matter how great the book is. It doesn’t matter if you pray everyday. It only matters if you lived a life that was meaningful to yourself and to others. And we all know what religion does to us. We’re so patriotic and fanatic about our own gods that we forget to think about our own people. We kill each other and say our gods made us do it. It is our hands, isn’t it? Which god would command us, force us, use us like that? We’re carrying it a bit too far. It’s getting to our heads, and we are forgetting to be what God made us, if ever there is a god. We’re forgetting to be human beings.’

‘And what about all of this? What do you think?’ I ask again, waving my hand at the little kids wearing bhoota masks and dancing around with lanterns. I want someone to just tell me that they don’t believe in the dark side, in the supernatural, or even that they do, just give me a fixed answer. I’m so bewildered, caught in wishful thinking, frail and injected by faith. I need a yes or a no, and I need evidence. I’m tired of hearing and seeing things, but never believing. My mind is always a crossroad.

‘In yakshagana?’

‘In ghosts…in the stories they weave for these dramas. I don’t know.’ I wave my hand carelessly. ‘In the supernatural.’

‘I don’t know anymore, what to believe or believe in.’

‘There are a lot of things about this place I’d like to not believe in,’ I add.

He grins. And then he’s suddenly grave again. ‘There are a lot of things I’d like to believe in. But above all, I’d just like to believe in myself.’

Me too, I want to admit. But I don’t know. I am in love with his thoughts. I don’t want to interrupt him, and I don’t want to interfere in whatever world he is losing himself in. It is of the most beautiful solitude. I could never pull it off. I can never draw the line between solitude and loneliness; somewhere they merge and become one.

I wonder if he ever feels the same way.

‘What after this?’ I whisper into his ear, and he looks at me smilingly.

‘Did you like it?’

‘I loved it. I’m slowly starting to understand the culture now. It’s a celebration of life and death. I don’t think the villagers are still used to me, but at least, they’re kind.’

‘They’ll come around, don’t worry.’

I like the sound of him when he’s reassuring, but I don’t tell him that. After another long silence, he says, ‘I’m going to show you something you will never forget next. It’s called a kola.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Kind of like a possession.’

‘What?!’

‘It’s not scary, don’t worry.’ He laughs at my expression. ‘Nobody is going to die. I hope.’

Aren’t you afraid of death? I ask him.

There are worse things than death, he replies calmly.

Oh? Like what?

Losing someone you love, he says.

I’m shut again. Sometimes he says such heart breaking things, it leaves me lost. ‘Kalki…’ I begin, but he interrupts me.

‘Shh. This is the main part. Watch.’ He diverts his attention to the stage again and I watch his expression change. It’s alert, full of interest and awe, and I’m more captivated by this personal show than what’s on stage.

I wonder what’s happening to me. This is more magic than I can handle.

***

At ten, we move towards a garden of tents. There is a big bonfire in the middle, and a couple of men holding onto someone with a mask.

‘This is a kola. That person is possessed by the village spirit.’

These bhootas are guardians of the village, of the Tulu tribes settled here. To appease and solicit assistance from the spirits, the villagers conduct this ceremony, he tells me.

‘Why are they holding onto him?’

‘Because he might harm himself.’

The man is dancing and wriggling and running towards the bonfire. I’m scared he might just jump, but the men are strong enough to hold him down. As I look into the eyes of the man who is performing the kola, I see death. They’re sunken and lifeless, and yet there’s a wild dance boiling inside them. The tension in the air is eerie, and I move closer to Kalki. I know that if I stay here any longer, it’ll ruin me. I turn to Kalki and I read the same expression on his face. He knows exactly what I’m thinking and he’s fearing the same thing. This is too much to see in one sitting. I’m on the verge of going crazy.

‘Do you want to leave?’ he asks me, concerned.

I shake my head. All at once, my curiosity has become an Achilles heel.

When we take our seats on the wet grass, the performer grabs a chicken passing him and bites into it. He gobbles it up raw, and there is blood everywhere. I look away, and the minute I do, Kalki’s hand shoots up and covers my face. His palm is resting lightly on my cheek, and he’s pulling me towards his shoulder.

I freeze. I’m terrified when boys are nice to me. It means I’m in trouble. It always means I’m in trouble. But now, there are worse things to fear, so I let him touch me, I let him support my head and protect me.

I close my eyes and sob into his shirt. I’m so scared of this. Living in a state of war was difficult enough. I don’t know which monsters are scarier. The human demons that we know or the unknown ghosts that haunt us. I can’t live like this. And he knows it too.

I realize I’ve slowly started believing the village’s horror stories.

Megha Rao is a confessional poet and a surrealist artist. Her two fiction titles, It Will Always Be You and A Crazy Kind of Love, were published by Penguin Random House India in 2015 and 2016. Megha is a Post Graduate in English Literature from the University of Nottingham, UK. When she’s not cafe hopping in Mumbai with a bunch of Sylvia Plath poems or Frieda Kahlo biographies in her bag, she’s curled up on her grandfather’s easy chair, her cats on her lap, back home in Trivandrum, Kerala.

Excerpted with permission from Music To Flame Lilies, Megha Rao, Tara India Research Press, available online and at your nearest bookstore.