Essay

The Pleasures Of Writing A Debut Novel

‘You must write a book!’

Ever since I can remember, long before I even became a writer, these words from my family, friends and well-wishers triggered a chorus in my head. One gentle voice whispered, ‘Do it. How tough can it be?’ A less friendly voice said, ‘But look at how Virginia Woolf wrote. You shouldn’t even try.’ The voice I identified as my own said, ‘Do I even care about writing a book?’ And so the voices went on.

Over the last seven-odd years, I’ve been an independent writer. About a year-and-a-half ago, I began writing my first novel. This November, it’s out in stores, published by HarperCollins India. The voices outside my head seem to be pleased. The ones inside, in their usual style, are harder to satisfy.

If there’s one thing that I have taken away from this wonderfully exciting, nerve-wracking, intimidating, gratifying, bewildering process of writing a first novel, it is that fiction is liberating. I’ve written cricket reports and film award speeches, ad campaigns for furniture brands and press releases for fashion houses, analyses of films and columns on everyday subjects, but no, nothing comes close. The beauty is, of course, that there is no brief. No pre-conceived audience. No blueprint. As a writer, I cannot think of a greater privilege. In general, there must be many reasons for wanting to write a novel. For me, there was one. It allowed me to play with words on a page in a way I had never imagined possible.

As an occasional writer of verse, primarily for my closed group on Facebook, I had for many years enjoyed that special, even secret, pleasure that only poetry can provide. The thrill of an exciting thought. The search for the right phrase or the right metaphor. The struggle – or flow – of meter. The surprise of words tumbling out from who knows where. When I began writing my novel, it wasn’t very different from writing poetry; it was both exhilarating and refreshing. Every new writer of fiction must bear the burden of the literary canon as they try to find their own voice. I decided to deal with what the literary critic Harold Bloom termed ‘The Anxiety of Influence’, in his book of the same name, by refraining from reading fiction altogether for the period that I was writing the book. I think of myself as a confident person but reading just a few lines by the sublime Iris Murdoch can turn me into a self-loathing mess. And so, I flung myself into the arms of some excellent non-fiction writers, no less literary or imaginative, but somehow less demoralising!

Oliver Sacks, neurologist, naturalist, writer and overall A-grade human, became a kind of guiding light as I clattered on. These were days filled with discovery. I figured that I knew nothing about the book I was writing. What I mean is, there were no lovingly maintained journals, meticulous Excel sheets, hurried Post-It notes. There was just me, my laptop and a self-imposed word limit. Part one of the writerly pact I made with myself was this: write 1200 words every time you’re at your desk (or more commonly, the corner of my creaky bed, under a blanket). Why 1200? Because that’s the point at which my rhythm would generally begin to miss beats. Unlike so many admirable authors, it was never my aim to push a heavy novel up a hill. I discovered that this book was fun to write early in the process, and I needed to stop being suspicious of that.

To follow the writing advice of writers is to set yourself up for failure. How does it matter how Dickens wrote? (Standing up.) Or what Hemingway drank? (Everything.) Or what instruments Jane Austen used? (Her desk is displayed at the British Library.) The less I art-directed this whole novel-writing business, the better luck I would have with it, of that I was sure. A few weeks into this pact, I realised my fingers would stop typing at around the 1200-word mark, all on their own. Just like the muscles remember how many squats to do or miles to run, so also the mind adjusts to word limits. On one special day, I stopped typing at exactly 1200 words. Oh, the cheap thrill!

Part two of the writerly pact decreed that I would read what I wrote on a particular day only on the following day. Putting at least a night between myself and my writing was an arbitrary policy, made in deference to the ‘sleep over it’ rule. It yielded quite a surprise. Reading over what I had written just a day ago, I found that I was processing the words as if encountering them for the first time. I’m not claiming a rare neurological condition here. All I’m saying is, it felt like the words, characters, feelings and events had come for someplace other than me. The words arranged themselves on the blank page; connections were formed; a plot revealed itself. What I had to do with all of this still remains a mystery to me.

One way to explain this fascinating phenomenon is by attributing it to the role of the unconscious in creativity. My experience was very far from that mystical activity called ‘automatic writing’, made famous by the Surrealists. And yet more often than not the material wrote itself. (Though the exacting edit process brought me right back into the realm of the conscious, kicking and screaming.)

I’ve spoken to some of my friends who are writers and they seem astonished by this ‘who wrote it’ phenomenon. ‘No, elves didn’t appear out of nowhere and write my novel for me,’ an author friend recently told me, with a touch of annoyance. This, in turn, made me think of another popular idea: everyone has a book in them. This one, quite certainly, was the book I had in me, longing to get out. Early readers of the manuscript (those closest to me) observed how the novel wasn’t as dark as they had expected it to be, and I agree.

Considering my taste in literature and my existentialist leanings, I too had expected a book with long-suffering characters dealing with crippling anxieties in a hostile world. Thankfully, what came out was a book leaning towards hope and light. I learned, while writing it (and reading it), that simple writing needn’t be simplistic writing. And that I am, at this moment in my life, quite tired of literary fiction about, what another friend calls, ‘the sad beauty of the world’.

(Image via The Writing Cooperative)

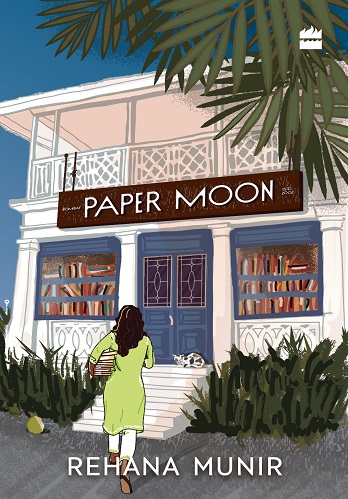

The primary dilemma that I faced as the book developed was to do with the biography versus fiction question. I was, after all, borrowing the premise from real life. My novel is set in a bookshop inspired by the one I used to run in Bombay in the mid-2000s. The protagonist, Fiza Khalid, is some version of me mixed with certain traits from others in my acquaintance. Events and characters from my own life made their way into the book, but in variations, combinations and settings that obliterated my fears all together.

This isn’t a roman-à-clef, where every character corresponds to a real-life person (with one notable exception). Not that I have anything against the style as a reader; as a writer, I just find it to be tedious. Like I said at the beginning of this essay: the book allowed me to play with words on a page in a way I had never imagined possible. Only fiction — without keys or strings — can ever give you that kind of license. Go forth and create! it said. I merely obeyed the order.

Rehana Munir ran a bookshop in Bombay in the mid 2000s and edited cricket websites a few years later. Now an independent writer on culture and lifestyle, she has a weekly humour column in HT Brunch, and a cinema column in Arts Illustrated magazine. Paper Moon, published by HarperCollins this November, is Rehana’s debut novel.

Read her articles here.