Essay

Why You Can’t Separate Story And Language While Writing

I read Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities in January 2019, amid birdcalls and a hard sun on my shoulders. I was in Goa, house hunting while trying to find the blueprint for the coming year. All I had was a reading list. I was reaching – fingers opening and closing – for what I wanted to do in writing.

Calvino’s book was a strange gift. It was unlike any book I had read: a travelogue of Marco Polo’s adventures as described to Kublai Khan. Both Marco Polo and Kublai Khan swim in and out of the pages, but the bulk of the book is dedicated to the cities Polo describes: a city that contains glass globes of once-possible but now-dead futures, a city where memory is traded each solstice, a city that traps you in your desire, a city that can be reached by camel or by steamboat and looks like a steamboat to those who arrive by camel and a camel to those who arrive by steamboat. Impossible cities – invisible ones. Each chapter is a city, usually a page, sometimes three. If you search for a pattern, for a plot, you will find it in a sentence: “Only in Marco Polo’s accounts was Kublai Khan able to discern, through the walls and towers destined to crumble, a tracery of a pattern so subtle it could escape the termites’ gnawing.” Calvino’s cities were not made of stone or street: they were made of concepts, the things that last.

Reading this book was like coming home. I was in awe. How had Calvino done it? He had transported me to ink maps of caravan routes, spice markets and azure seas, all the while discussing content found in a philosophy manifesto. His language sang but also embedded roots so deep, it was impossible to see where they ended.

I took an intellectual scalpel to the text, cutting away lines, looking at the architecture of the sentence, tracing how a chapter became. But Invisible Cities, exactly like a city, functions as a whole. Each sentence links to the one that came before it, each idea is an echo of a concept already expressed and only makes sense when placed beside that concept. It is a novel where a sentence feels perfect – the length, punctuation, shape and movement carrying you towards the next sentence, pushing you forward – and yet, pluck it from the whole, set it apart, and some meaning is lost.

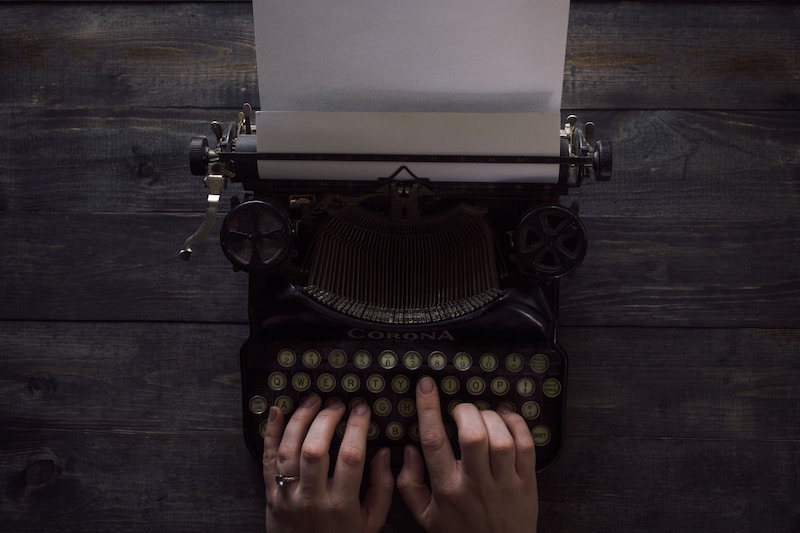

A friend once described writing to me as a magic trick: creating illusions out of words, conducting the hard work (the sleight of hand, the card switching, the handkerchief tucked up your sleeve) in the white space around the text. Good books always read like that: astonishing, wondrous. You know there is machinery somewhere, some sort of plotting or sweat that shaped this experience, but the experience itself cannot be broken into pieces. Was it the magician’s presence that made you shiver in terror as he promised to cut his assistant apart? Was it the lights or the assistant’s awe that made you gasp as the magician levitated? You don’t know. You’re not looking for the wire holding him up. You accept, you trill – you’ve surrendered to the illusion.

(Image via Angelina Hue)

Calvino taught me this. Anything good is a whole, impossible to carve into parts because it is more than the parts. And perhaps what we’ve been doing for so long, by dividing story and language when we analyse writing, is failing to understand the dialogue they establish between themselves in order to create something living. In good books, language and story are the same thing.

An easy way to describe this would be through the metaphor of a house. A novel builds its story in words, in language and sentences – the bricks of the house. You need the bricks to make a house. But the story tells the language where it needs to go, what sentences fit the content and in what order – the house’s blueprint.

It’s an easy metaphor but also not quite right. To see them as ‘bricks’ and ‘blueprint’ is to separate them too much. It would be better to think of story and language as the two colours of a two-toned cloth – distinguishable at certain angles and yet the same. You cannot separate them. The language you choose creates the story and the story chooses the language.

When I finished Invisible Cities, I thought about my notions of balance and how I assumed I had to choose between language and story, mix them up in the right proportions. Where do they come from, the categories? Why do we elevate them into a question that must be answered? I don’t know. I only know that chopping the writing up into parts makes us feel more in control. Like there is a formula to this, a secret order waiting to be discovered. We’re the audience member at a magic show looking for the wire. We’re the ones biting our nails and telling ourselves that if we make a list of all the aspects – the assistant, the lights, the magician’s speech – then we can do it too.

But it doesn’t work like that. Take apart Invisible Cities and it loses its magic. Divide language and story and you’d be doing them a disservice, lessening their true nature so that you can feel in control. What we seek can only be found in the whole – a tracery of a pattern subtle enough to survive the termites’ gnawing. Something alive; something magical.

Tashan Mehta is a novelist based in Mumbai. Her novel, The Liar's Weave, was published in 2017 and she has been longlisted for the Prabha Khaitan’s Woman’s Voice Award. You can find out more about her at tashanmehta.com.

Read her articles here.