Essay

Why Schools Should Encourage Students To Read Indian Classics

In 2012, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) prescribed eight classic novels as extended reading for Classes IX to XII. According to their notification, the books were selected in order to ‘foster good reading habits’. The eight books were Three Men In A Boat by Jerome K. Jerome, Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, The Story Of My Life by Helen Keller, Diary Of A Young Girl by Anne Frank, The Canterville Ghost by Oscar Wilde, The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells, Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington, and Silas Marner by George Eliot.

While all the books on the list have merit, I find it difficult to believe that the CBSE could not find a single piece of Indian literature or contemporary literature to warrant an inclusion there. I don’t want Indian representation for patriotic or nationalist reasons. I want it because introducing readers to books that are relevant to them is one way for the CBSE to foster good reading habits. Otherwise, forget good reading habits, we will be lucky if they have any reading habits at all! I doubt Silas Marner or an unabridged version of Gulliver’s Travels will hold many young teenagers spellbound even though both are excellent books in their own right. Besides, is literature’s only purpose to encourage good reading habits? Surely not!

So, how should one put together a required reading list for Indian high school students? And what should a reading list’s objectives be?

Using Required Reading To Explore The Classics

Language curriculums have used required reading lists for nearly as long as institutional education has existed. This is because language education is not just about learning how to read and write. Literature is included in language curriculum because it is one of the most powerful mediums to communicate ideas related to culture, politics, philosophy, and even our understanding of human nature. The Jules Verne classic Journey To The Centre Of The Earth might be fiction, but I’m sure it inspired generations of geologists, biologists and travellers. Fiction animates dull facts in a textbook. It can make people comfortable with new cultures or beliefs and do the same for their own. Finally, it can transform the reader to be more empathetic by allowing them insight into different ways of thinking and experiencing the world.

Fiction and nonfiction can do all these wonderful things. But how do you get them into the classroom? Language teachers have been using prescribed reading to tap into these different functions of fiction. The books they select contain good writing because, as a high school teacher says in an article for The Atlantic, ‘good writing tends to focus on difficult-to-deal-with themes because those are the themes difficult to understand.’

This is why prescribed reading lists are often full of classic literature. These are books that have stood the test of time. They are ‘good writing’ and, just as Italo Calvino says, can be read over and over again – each reading giving the reader a new insight and lesson.

When I look back at my own high school years, there are books I would not have touched with a ten-foot pole had they not been forced upon me. Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness or James Joyce’s Dubliners are both books I might not choose to pick up today, but have somehow made me a more compassionate and less judgemental person. Joyce did not write Dubliners with the intention of teaching us some moral lesson. He just wrote powerful short stories about ordinary lives in Dublin. But the fifteen-year-old me who read it gained insight into the damage poverty and alcoholism can cause to the human spirit. In that sense, literature is more powerful than moral stories because it does not force a lesson on their readers – it allows them to arrive at their own conclusions.

In my teens, however, I was never introduced to Indian classics. In fact, until I joined a writer’s workshop that had its own prescribed reading list, I had not even read an R.K. Narayan book. Slowly, I realised I had missed out on a lot – a whole lifetime of reading. There were the early Indian writers who wrote in English – R.K. Narayan, Raja Rao, Mulk Raj Anand, Kamala Markandeya. And then there were the many writers who wrote in regional languages. You are indeed lucky if you can read an Indian language proficiently enough to tap into regional literature. But with more and more regional literary classics getting translated to English, it is time these books found their way to classrooms around India.

Introducing Students To Indian Classics Early

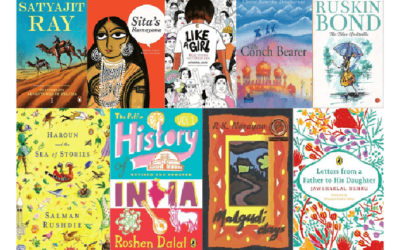

Starting in middle school, English students can begin with classics like Narayan Gangopadhyay’s Tenida or Satyajit Ray’s Feluda. Thankfully, several schools are already prescribing books by Ruskin Bond, Sudha Murthy and R.K. Narayan. For an urban Indian child, these books illustrate Indian social history better than any textbook. They tell us how families lived, how friends spent their time together, what our society valued at one point and it invites the reader to analyse how things have changed now, if at all.

In high school, prescribed book lists can recommend both well-known Indian and Western classics as well as little-known gems like A. Madhaviah’s classic Padmavati. Madhaviah wrote Padmavati in the 1890s. The novel spans several years and describes Tamil society bluntly but never cynically. Madhaviah was a social reformer who wrote of friendship, infatuation, love, and the challenges in marriage. For an adolescent reader, this book is a good way to gain a far better understanding of how caste and religion influenced daily life, about child marriage and the life of widows than any social studies lecture. Because it is written in that time period, he is not writing with retrospective judgmentalism. There is much to be gained by reading literature that is honest and open, especially for young readers who will be able to make independent judgements about the social and individual needs of the time.

Literature, however, need not be restricted to modern fiction. In the Western canon, Plato, Homer and other Greek classicists are introduced to young students as a way to explain basic fundamentals of Western culture and philosophy. I wonder if in India, we relegate classic texts like the Bible, the Upanishads, the Quran, the various Gitas as only the concern of religion. These texts influenced thinkers like Ambedkar, Gandhi, and others who laid the foundation of modern India. Students should be given a chance to explore these classic texts – debate them, challenge them and be challenged by them. Currently, they seem to be treated as sacred, esoteric spiritual texts. While that may be true, they also have a foot in the practical world as well.

Similarly, the poetry of Mirza Ghalib or Muhammad Iqbal can be a part of required reading as they are a part of India’s cultural heritage. While it would be wonderful to explore them in their original language, translated works are as important because they still give us a chance to learn from them. For all you know, it might inspire readers to pick up a new language to explore these works in their original form.

(Image via Steelcase)

Why Required Reading Lists Matter

But why should reading lists be a part of classroom learning? Reading classics in a classroom gives students an opportunity to not just read but also discuss these works. Listening to a variety of perspectives on the same set of words broadens our horizons and provides a deeper understanding. Listening to a teacher or a peer talk excitedly about something they gained from a piece of prose or poetry can open an uninterested reader’s eyes to a new way of exploring the same text.

In my classroom, I use required reading as a way to expose my students to the many different colours of life. In an English class I am currently teaching, we are reading one translated short story from the different states of India every week, and we do this over a meal. This week, we shared hot luchis and phulkopir dalna while reading Tagore and discussed family structure, child marriage, the role of women in society in the early 20th century. After discussing the setting and each character at length, the children asked if they could put a play together to share the story with the rest of the school. They will now spend the next couple of classes rewriting the short story as a play. Of course, I am lucky enough to be able to do this because of my small class size. All teachers do not have that luxury.

When I look back at how I came to love reading, I realise there have been two significant influences on my reading life. The first was growing up surrounded by books. But, the second was being blessed with brilliant English teachers whose classes I would find myself in once every couple of years – teachers who not only loved books but who loved talking about them. These are the teachers who allowed me to move past the challenges most young readers face when they encounter the classics – the stuffy language, the peculiar sentence structure, the occasionally alien and unrelatable setting or characters. They facilitated conversations around these books and showed us how they mattered.

On occasion, when I encountered texts or books I could not relate to, the same teachers allowed me to feel a dislike for it but encouraged me to express it constructively. This way, I learnt that even a classic that missed its mark with a reader could teach her something. For reading lists like these to really work, teachers should be given some freedom to choose what works best for them and their class.

Personally, I do not know if the students in my English class will develop a love for reading based on how we have been exploring literature currently. And truthfully, it is not an agenda I am really pursuing to begin with. What I do want to do is share my love of language, culture, and food with people who are willing to listen and listen to them share their ideas on those subjects too. That conversation is what excites me.

If teachers and students get the space they need to explore literature as not just reading a string of words put together elegantly, but as a joint exploration of ideas, stories and characters, real magic happens. Reading becomes pleasurable. Doors are opened, and there is a chance for transformation for everyone involved.

Saisudha works at a small democratic school in Bangalore where she 'teaches' history, economics and anything else the children are interested in. She loves her job and one of the reasons she loves it is because she can drag the books she loves into conversations and lessons she plans. When she is not working, she is either reading or listening to books and podcasts. She has a particular soft spot for historical fiction, creative nonfiction, but mostly children's literature - even picture books get her excited. Her favourites are any books by authors like L.M. Montgomery, E.B. White, Kate Di Camillo and Neil Gaiman. Nothing can beat the high she gets when a child comes rushing back to her with a book that she recommended, telling her how he or she loved it and why.

Read her articles here.