Essay

Conjuring Punjab In Pedemontana Trevigiana

The town of Asolo, in Italy, is known as ‘the city of a hundred horizons’ because of its many stunning, panoramic views of mountains and the countryside. It is also where my wife and I have a holiday home. We were married there in 1977 at the church of Santa Anna, because the one in my wife’s hometown was undergoing repairs. Thus, Asolo holds a special place in our hearts. Its seven hills are part of the Pedemontana Trevigiana, the foot of the mountains in the lee of the Dolomite Alps.

For the past 12 years we have been coming here at the beginning of September for several weeks to help my wife’s elderly parents harvest their grapes, and, if time permits, their olives, too. It is hard work, done mostly by hand in day-long shifts. When Mother Nature is kind, we can end up producing numerous barrels of eight varieties of wine, while the olives are pressed into many litres of the finest extra virgin oil. The olive oil from the family grove has won an award for the best in the region, a very proud accomplishment for a hard-working farmer.

When I am in Asolo, away from the distractions that tend to hijack my attention at home, it’s always my goal to spend a good deal of time on focussed writing. But first, a full day of work awaits.

A typical day begins early, when we start by cutting the grape variety that has just ripened. As our crates fill, two individuals lift them onto a tractor trolley, and they are hauled to a covered shed. There, they are put through a destemming and crushing device, and the slurry is pumped into huge plastic barrels. After the slurry is pressed to separate the juice from the seeds and the skin of the grapes, the juice is pumped into tall steel barrels to begin the three month-long maturation that must take place before the wine is ready to drink. The process is artisanal and organic; no preservatives or chemicals are used.

If our day’s work is in the olive groves, we face a different kind of challenge. The olive trees stand on the slope of a fairly steep hill, and wide nets must be laid down before the olives can be harvested. Maintaining one’s balance on the slippery nylon of the nets while combing the branches with long-handled rakes is a tricky business. At the end of the day, we gather and crate the olives, transport them to the covered shed, put them through a separator to discard twigs and leaves, and then the day’s harvest is sent to the local co-operative, where the olives are mechanically pressed and the oil is extracted to be stored in steel containers.

The best part of the harvest is the picnic at lunch, a peasant meal of bread, cheese, and cold cuts chased down with wine. And whether we’ve been harvesting grapes or olives, by the time we finish our work it’s nearly dusk, and our reward is a few minutes spent admiring the transcendentally beautiful sight of the sun setting among the hills.

(Image of Asolo via Asolo.it)

Of course, on our days off my plan is to sit down to write. But we can’t come to Italy and not spend time visiting uncles and aunts, and my wife has seven on her father’s side and ten on her mother’s. We take day trips to Venice, an hour’s drive from Asolo, or to the Winter Olympics city of Cortina deep in the Alps, or to the Austrian border and the valley of Asiago, famous for its cheese. We might also make a day trip to Monte Grappa, the mountain whose shadow falls on Asolo. Near the summit, a military mausoleum honours the 25,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers who lost their lives there in the battles of the First World War. In the mausoleum is the grave of a young soldier named Peter Pan, and my children, and now my grandsons, lay flowers there. I cannot say enough about the historical landmarks in the area, and the beauty of towns like Marostica, where every two years, in September, a live game of chess is played, with real people and horses, on a huge board painted in the town square between two towers, from which the players call their moves.

In the evening there is time, at last, to write. But needless to say, our evenings are dedicated to food, and to enjoying the specialties of local family-run restaurants in Asolo and the surrounding towns and villages. This is not an area frequented by hordes of tourists, so the prices are reasonable, and the quality of ingredients is the best. It is also a chance to enjoy the wines from the region. A variety of wild, locally hunted game—rabbits, ducks, deer, and wild boar—add to the culinary experience, along with an array of fresh seafood from the Adriatic and Mediterranean seas. I rarely put on weight despite the gluttony thanks to my work in the vineyard and the olive grove.

(Image via Wine Enthusiast Magazine)

Finally, at the end of it all, there is time to write. And I happen to do my best writing in Asolo. The routine is to write from nine or ten at night until the wee hours. After spending my day in the Italian countryside and gorging on fine pasta and wine in the evening, it is quite the challenge to transport my mind to the gritty, rural settings of my stories of Sikhs and the Punjab. So, over time I developed a routine.

- Find a quiet spot in the house.

- Lubricate the mind with a healthy pouring (a Patiala peg) of single malt scotch.

- Select the most evocative Punjabi songs on YouTube, put on headphones, and turn up the volume.

- Half an hour in, have a smaller Patiala peg.

- Once the senses awaken and I can smell the smoke from my grandmother’s chullah and feel the grit of dust swirling in the fields of my grandfather, let the mind wander.

- Take off the headphones, pull up yesterday’s writing, and begin a slow read. Correct and edit.

- Pour another small Patiala peg.

- The Punjab is now in me and I am in the Punjab.

- Start writing and stop only when I can no longer focus on the screen.

- Shut everything down and crawl to bed.

- Wake up to the beauty of Asolo, breathe in the clean mountain air, and fortify myself with a gulp of espresso.

- Thank God that there will be an afternoon siesta!

When I first visited this region in 1976 there were no Indians here. Over time, however, migration has increased and now, according to a local priest who is involved in immigrant settlement, not only are there Indians in Asolo, there are about 28 different nationalities residing there. There is even an Indian restaurant and a grocery store in the nearest large city, Bassano del Grappa. Turbaned Sikhs and women in traditional Punjabi clothes shop in stores. It is a good day when I get to meet them and converse in Punjabi. I can even buy ready-made, heat-and-eat pindi channa at a local grocer’s store.

The other night, on a weekend, as I was getting ready for my routine of conjuring up Punjab, I thought I heard something strange. I asked my wife to step out with me onto the patio as I could not trust my ears. The sound became louder once we opened the triple-glazed door. She turned to me and her lips formed an O. It was bhangra music wafting from the valley below. I looked down toward the lights about a kilometre away and made out figures dancing together. I waited, not believing my eyes or ears.

The next song was pure Punjabi and the beat made my heels ache. I ran in to pour a Patiala peg.

‘Heer Ranjha’ wafted up the hill . . . ‘Heer akhdi jogia jhoot bolen, kaun vichre yaar manavda yee . . .’

Waris Shah was in the Pedemontana Trevigiana, and I was in my beloved Punjab.

Read an excerpt from Sohan’s book Paper Lions here.

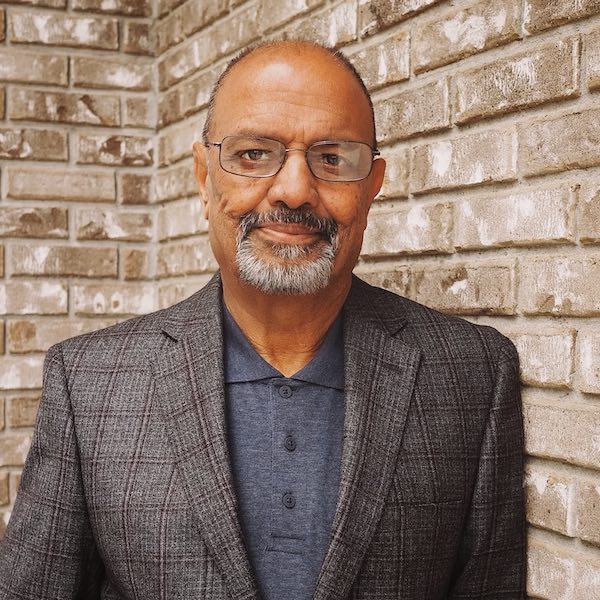

Sohan S. Koonar has lived on four continents: Asia, Africa, Europe and North America. A physiotherapist by training, a founder of a multi-clinic company and an inventor with international patents, Sohan’s passion for storytelling won him the Judges Choice Award in the Toronto Star Short Story Contest and the first Burlington Library Literary Excellence Award. His self-published novel Karam’s Kismet drew mentions in sixteen dailies and periodicals in the US. Sohan spends the year in his family homes in Canada, Italy and India. He is currently working on his next novel.

Read his articles here.

“The Punjab is now in me and I am in the Punjab.”

“I AM THAT I AM”

good place to write from <3