Essay

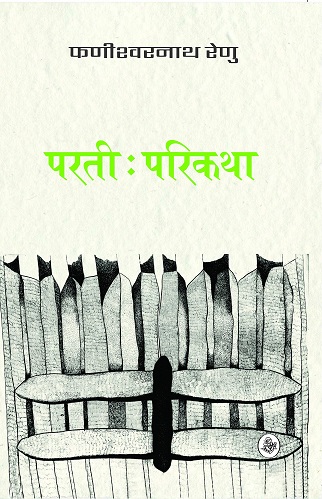

My Memories Of Reading Parati Parikatha

I have read somewhere that we have memory-triggers, that the flavour of a favourite dish or a particular fragrance could bring back memories, elaborate with details and drenched with joy or sadness that was long forgotten.

Books, for me, are these memory-triggers.

Books occupy a special place for me. The house I grew up in had books everywhere. They filled shelves and wall-niches and lofts, revolving bookcases groaned under their weight, they were piled up on tables and often under my father’s bed. In fact, some of my earliest memories involve books – my father sitting up in the bed, a pillow caught in his lap, reading from several books at the same time (or so it seemed to me), my mother relaxing in the afternoon with a book in her hand, her beautiful eyes gliding over the pages. Even before I could actually read, I used to pretend to read books, mimicking my mother, turning pages and smiling and frowning like her.

One summer, my father made up a ‘where-is-that-book’ game for me and my sister – he would name a book and we would have to find it among the uncatalogued multitudes scattered all over the house. He was writing the thesis for his D.Litt. at that time, a seminal work on the Nai Kahani movement in Hindi. Now that I think about it, this game was perhaps his way of enlisting our help as his book-searchers! The game stuck though, and I became so good at it that he only had to name a book and I would rattle off the author’s name and the book’s location:

‘Jalati Jhadi!’

‘Nirmal Verma, third shelf from the top.’

‘Ek Aur Zindagi!’

‘Mohan Rakesh, revolving bookcase.’

From searching for books, I seamlessly moved to reading them. I became a compulsive reader. Whenever I found a book that seemed interesting, and most books did to me, I forgot everything about the time and place and sat down to read it.

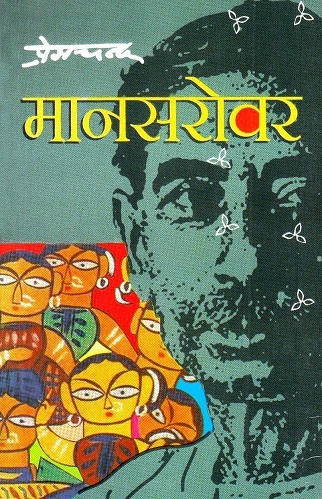

My mother often found me reading in odd places during the long summer vacations – standing on a stool, engrossed in a volume of Munshi Premchand’s Mansarovar that I had picked out from a high shelf; wedged behind a bookcase, reading an old copy of Panchatantra that I had found behind it, unbothered by the sweat dripping down my face.

One day, she found me sitting on the cool, mosaic floor of the covered veranda, puzzling over a thick book. She watched as I read, turning the pages back and forth, reading and re-reading. She took the volume from my hand and glanced at the cover. A frown formed on her moon-like forehead.

She took me by the hand and marched me to where my father sat writing.

‘You gave Anu Parati Parikatha to read?’ she demanded.

My father looked up. ‘Yes,’ he answered, looking at me over his reading glasses.

‘She is not yet 10, and you give her this book? She has been reading the same page again and again. How is she supposed to understand a book like this?’

‘That is the whole point,’ said my father cryptically and resumed his writing.

My mother sighed. Later, she gave me books more suitable for my age – Jataka Katha, Hitopadesha, volumes of a children’s magazine called Bal Bharati and many more.

But I was transfixed by Parati Parikatha and the lyrical language used by Phanishwarnath Renu which changed from the pure, gleaming beauty of Sanskritised Hindi to the soft silken skeins of his local Maithili. I was mesmerised by the prose melting into a song and the onomatopoeic words used to describe the sounds of the landscape – calls of birds, the river’s flow, a sarangi’s tune, the sound of machines.

I did not understand this language, woven from so many different strands, but was enthralled by the words that were incomprehensible to me, whose meanings were obscure but whose beauty was still revealed in the pages of Parati Parikatha. It made me wonder what it would be like to truly understand what they meant.

And so, I resorted to the Brihat Hindi Shabdkosh, the go-to dictionary in whose yellowing pages and musty smell I regularly lost myself. It was a massive tome – hardbound and covered in maroon cloth, so heavy that I couldn’t pull it out without help. I laboriously looked up the words – the smooth, hard gems of tatsam words drawn from Sanskrit, the malleable clay of the tadbhav ones, the regional deshaj words wafting an earthy petrichor and a sprinkling of videshaj words imported from foreign languages. Even before I formally learnt that Hindi, as we know it, is formed of these four types of words – original Sanskrit words, words derived from Sanskrit, words from local/regional languages and words from foreign languages ranging from Arabic and Persian to French and English, I experienced the beauty of their coming together in Parati Parikatha.

It was much later though that I came to appreciate the many literary merits of this socio-political romance woven so deftly by Renu, the wealth of unforgettable characters that he created, the masterly way in which he crafted two stories in two different time-periods, entangled them and then tugged at the strands like a magician to undo all the knots. The songs and customs and rituals that he described so lovingly, the prejudices, caste-injustices and exploitations that he portrayed so mercilessly, and the idealistic resolution of all that ails our society, that he imagined so poetically, brought not only the region but also our national dream alive for me.

In Parati Parikatha, I saw the river-plains of Kosi and the people who inhabit them in all their idiosyncrasies, wiliness and innocence. I also saw the social significance of the various love stories that run through the narrative – that of a brahmin landowner and an English woman, of an idealistic upper-caste dreamer and a woman from the clan of prostitutes, and of an upper caste boy and a Dalit girl.

It took me even longer to understand that his unapologetic and liberal use of Maithili was an act of rebellion against the homogenised, literary Hindi in vogue and that it established a new genre of writing in Hindi. Writers began telling stories of villages in a language that retained the regional flavour, that wasn’t scrubbed and made alien in a way that created a distance from the land the words described. The stories became more authentic because of the living, breathing language they were written in.

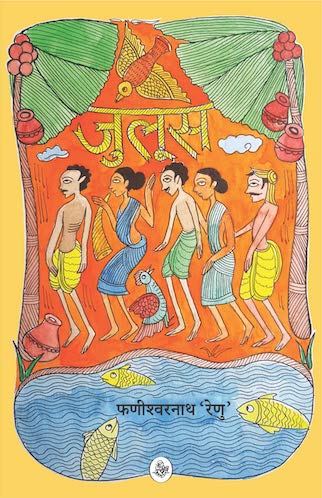

I still remain enamoured by Renu’s writings and have devoured his books from Maila Anchal to Juloos to Van Tulsi Ki Gandh as well as his exquisite short stories – ‘Raspriya’, ‘Lal Paan Ki Begam’, ‘Teesri Qasam’ (which was made into a popular movie starring Waheeda Rahman and Raj Kapoor), and many more. I have also read the works of many other authors who wrote in the regional genre Renu pioneered and have tapped into the rich language and traditions of Bihar.

But Parati Parikatha, the story of a barren land bursting into green growths, set to the cadence of Maithili folk songs, remains unparalleled to me and is a literary treasure which deserves its place in world literature. Every time I open my volume of Parati Parikatha, I remember the summer afternoon, my bewilderment, my intense wish to penetrate through the fog of my incomprehension and see the beauty that I knew, even then, lay hidden in the words.

And, I think of my father who knew well before I did that I was ready to begin my quest.

Anukrti Upadhyay writes fiction and poetry in both English and Hindi. Japani Sarai, a collection of Hindi short stories and two English novellas, Daura and Bhaunri, have been published to date, and a number of works are in progress. Her short stories have appeared in numerous prestigious literary journals. With post-graduate degrees in Management and Literature and a graduate degree in Law, she also wrote a doctoral thesis on Hindi Literature. She divides her time between Bombay and Singapore.

You can read her articles here.

I relate with what you have written here. I used to get my mother Hindi novels from the College Library where my father used to teach English. I had all the information where one can find a particular novel or poetry of a particular author. While I was inside the Library (I was the privileged one to go to the stacks inside), I was in a different world. I used to think if I could live there forever, or at least have an opportunity to stay there at night. Love for books lives forever.

So true. Thanks for reading and writing in.