Essay

Who’s Afraid Of Faiz Ahmad Faiz?

I don’t remember the first time I read the poetry of Faiz Ahmad Faiz. It was definitely a long while ago, well before it became fashionable to be ignorant, to partition poetry, abuse poets, and generally behave boorishly.

I read Faiz’s works just like I read the works of other masters of the art and craft of shayari, such as Mir Taqi Mir, Mirza Ghalib, Josh Malihabadi, Majaz Lakhnawi, Firaq Gorakhpuri. I read them, in no particular order, as and when I came across their works in the various libraries I was fortunate enough to have access to, including my father’s.

Occasionally, a particular verse, recited by my father or uncle or one of their numerous friends, acquaintances, and students who visited our home, would move me with its ineffable beauty. It would cause my throat to fill with tears and my eyes to smart, and I would go looking for the rest of the poem. I read the poets initially for the ambivalent, often obscure, beauty of their words. Slowly, gropingly, entranced by what I half-understood, half-sensed, I tried to make my way to the heart of their poetry.

I formed my own uneducated conjectures about the poets I read and, with copious amounts of help from dictionaries and kind-hearted visitors who suffered a precocious youngster with patience, deduced the meaning of their dazzling, mellifluous words. In my unformed and uninformed mind, Mir became the singer of unrequited love, Ghalib of melancholy and self-destruction, Josh of nostalgia, Majaz the complex and enchanting poet of angst, feminism, and sensual love, Firaq of delicate, sentimental poetry, but Faiz stood alone.

For me, Faiz was the ultimate rebel poet, the one who came the closest to the poetic ideal of warrior bards of the Rajasthani folklore I had grown up hearing and reading, those who held a pen in one hand and a sword in the other. I read and recited his ‘Mujhse Pehli Si Muhabbat’, an ode to empathy in which the suffering of others triumphed over romantic love, and ‘Bol Ke Lab Azaad Hain Tere’, in which he urges everyone to speak up in protest, and by protesting, prove that they alive and sovereigns over their own bodies and souls. His electrifying words settled in my memory and unsettled the cosy comfort and sweet melancholy that poetry usually yielded.

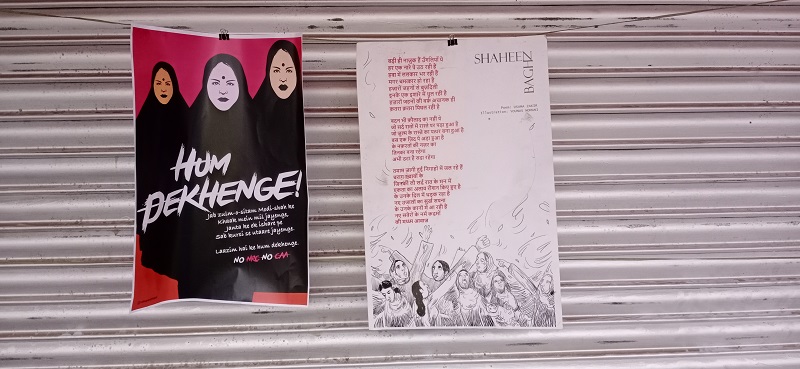

But the real revelation happened when I discovered Iqbal Bano’s full-throated rendition of Faiz’s ‘Hum Dekhenge’, a poem about a people’s revolution and the unseating of the mighty. Bristling with angry beauty, the nazm truly came to life in Bano’s gloriously taunting and powerful rendition. Through her fearless defiance in singing the poem on Faiz’s birth anniversary during the oppressive regime of General Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan, she turned it into an anthem of resistance. ‘Hum Dekhenge’ became a gauntlet thrown down by the artist, disguised as poetry.

When she sang the immortal, electrifying lines – sab taaj uchhaale jaaenge, sab takht giraae jaaenge, the challenging words which threaten oppressors, which acknowledge the abjectness of the exploited yet promise that they shall rise and overwhelm the powerful, that term the upheaval of world-order as preordained and celebrate in anticipation the ascent to power of today’s weak, thrilled through me, just as they have thrilled through untold numbers of listeners. In Bano’s soaring cadence, ‘Hum Dekhenge’ struck fire in the hearts of the listeners and simultaneously chilled them to the bone with an unrestrained call for a mighty revolution.

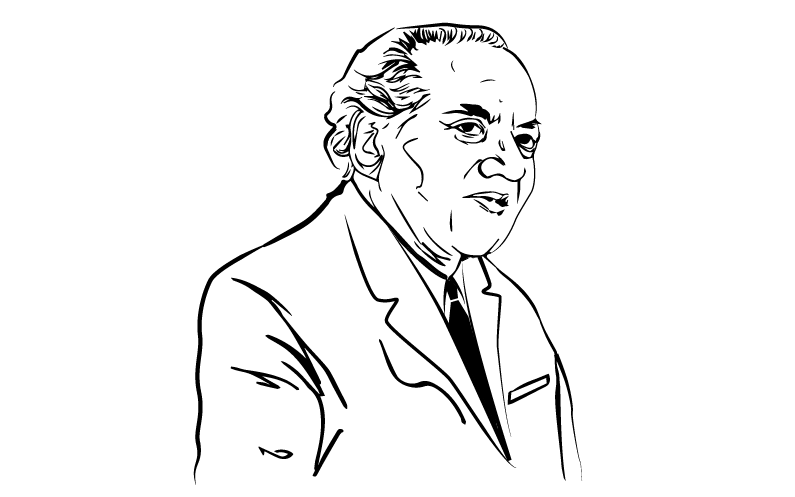

(Iqbal Bano, who first sang ‘Hum Dekhenge’; Image via iDiva)

I became absolutely infatuated with this nazm of resistance. I recommended it to everyone, listened to it on loop everywhere – while on the road, cooking, exercising, gazing at the sunset. Then came the news that someone who teaches, and therefore has the responsibility of shaping young minds, had complained against the singing of ‘Hum Dekhenge’ at a protest. It hurt his fragile religious feelings which had managed to remain unhurt by centuries of religious persecution of women and bahujans. His delicate sensibilities had been unaffected by the oppression perpetuated and crimes committed under the protective mantle of religion. The rapes, exploitation and lynchings had left his tender heart unmoved but this poem had, nevertheless, managed to hurt him. Such is the power of poetry.

But this wasn’t the end of the story. The premier institution of applied and pure sciences where he teaches opened up an inquiry on whether the nazm is indeed offensive to the followers of a particular religion. A committee would sit in judgement over the nazm – it would take the poem apart, test its context, weigh its words, construe its meaning. Such is the helplessness of poetry.

(Image via Wikipedia)

While I was still aghast at this Kafkaesque trial of a poem by scientists and academics, a floodgate of ignorance burst elsewhere. Who is Faiz? Why is he such a big deal? These questions were asked with the supreme arrogance of the ignorant. A floodgate burst inside me as well. And, I wrote a poem in order to answer these questions which, in truth, insulted only those who asked them. A nazm, however meagre, to explain a poet, a word-offering to an artist of language. It was my attempt to stand up against the swirling currents of malicious ignorance. It was one of the lessons I learnt from ‘Hum Dekhenge’.

कौन है फ़ैज़

कौन है फ़ैज़, पूछते हो तुम

कौन से मुल्क़ का बाशिंदा है?

याद उसको क्यों बारहा करते

ज़हन में क्यों तुम्हारे ज़िंदा है?

कौन था फ़ैज़? फ़ैज़ दरिया था

रंग था, ख़ुशबुएँ और बादल था

आँधी-तूफ़ाँ था और सबा था वो

लाल परचम था उड़ता आँचल था

इश्क़ की दिलरुबा सदा था वो

और मज़लूम की दुआ था वो

उसके लफ़्ज़ों में दर्द सबका था

सबके जैसा मगर जुदा था वो

अश्क़ भी था वो मुस्कुराहट भी

इल्तिजा भी और तंबीह भी

नर्मियाँ था वो सरकशी भी था

फूल-गजरा था और तस्बी भी

अब भी जाने नहीं अगर उसको

क्या बताएँ कि क्या नहीं था वो

नज़्में उसकी पढ़ो तो समझोगे

ग़लत कहता था या सही था वो

(Image via India Today)

Among the innumerable uncertainties of life and art, by reading Faiz and experiencing his poetic revolution, one rebellious nazm at a time, I have gathered some certainties. For example, I know now that when everything else will fall, poetry alone will remain standing, fighting at the frontiers of resistance and art, conjuring hope out of despair, mutiny out of misery. I know that though there is place for everything in poetry, it is not love or self-indulgent melancholy, hysteria or pathos, but rebellion which is the dharma of poetry.

I also know that if ‘Hum Dekhenge’ is blasphemous, so is the lament of those who are being crushed by an iniquitous system and the chants of those raising their voices against oppression. For that is what ‘Hum Dekhenge’ is – a spirited song of freedom from injustice.

Anukrti Upadhyay writes fiction and poetry in both English and Hindi. Japani Sarai, a collection of Hindi short stories and two English novellas, Daura and Bhaunri, have been published to date, and a number of works are in progress. Her short stories have appeared in numerous prestigious literary journals. With post-graduate degrees in Management and Literature and a graduate degree in Law, she also wrote a doctoral thesis on Hindi Literature. She divides her time between Bombay and Singapore.

You can read her articles here.

I LOVED THIS.