Essay

Why Coming-Of-Age Stories Crowd My Bookshelves

I found Rainbow Rowell’s Eleanor And Park in my late 20s. Or, maybe, it found me. It was stacked on a white bookcase inside a tiny tea shop – the perfect space to read something warm and comforting. Or, a book that causes a strange little pain just below your ribs, as this one did. Then again, most coming-of-age stories that talk about love (and many of them do) have that effect on me. I suppose it’s because my heart never really got over its angsty teenage self, nor saw love as anything other than utterly overwhelming, sometimes hilarious and, most of all, incomprehensible.

Rowell’s wasn’t the first coming-of-age story I read, but I hold it up as a landmark in my reading life because it pulled no punches about the quixotic mess that denotes our teenage years. And, because it started me down a path of reading similar stories that somehow fit me and my forever-adolescent heart. In theory, and sometimes in practice, the qualities these works denoted – the natural urge to put love first, the importance of liking yourself before loving another, the ability to look beyond external differences – continue to shape who I am, and how I love.

(Mis)fitting In

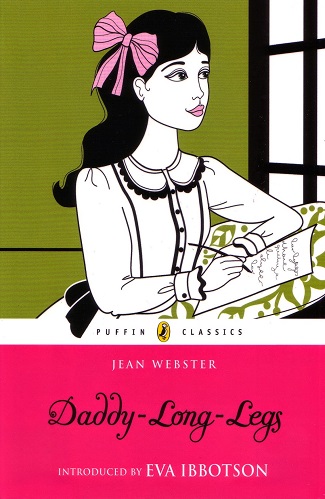

While Rowell packed a punch filled with realism amid romance, my journey of coming-of-age tales started years earlier, with the epistolary classic Daddy-Long-Legs. As heroine Jerusha Abbott battled poverty and glaring social inequality with determination and a sense of humour, it was apparent to me, at the age of 11 or 12, that the weird, the outcast, the misfits often ended up having the greatest love because they stood their ground and refused to blend in. Mind you, re-reading it many years later found me distinctly uncomfortable with the romance – I saw a blatant example of a male saviour complex and the manipulation of a young, spirited female mind. As a pre-teen, though, what stood out for me was that Judy (Jerusha) and ‘Mr Smith’ were, in a way, looked upon as strange and far too original. Coming together, they found their own original, albeit problematic, romance.

Similarly, in Eleanor And Park, Eleanor is a messy-haired redhead of generous proportions that promptly thrusts her into the category of ‘big girl’, earning her the jeering nickname of ‘Fat Chipette’. Her home is in pieces, with three siblings squashed into one room, and an abusive stepfather. Into this mix steps Park. Asian-American, even-tempered, despite his Taekwondo prowess, shrugging off the not-so-subtle racism aimed his way by his peers by donning giant headphones. The two of them are initially united by a common apathy – that world-weary, eye-rolling cynicism so unique to teenagers. Eventually, though, they find something to fight for and care about – each other. Awkward and poignant as first love and lust always is, what stands out is their refusal to try and change one another. Misfits united in love, against a world constantly trying to bully them into fitting in!

Touch, Don’t Go

The element of touch, of deeply felt physicality and of keenly observing the beloved’s body, and, by extension, the physical world, is a common thread across many love stories featuring young adults. A lot of this is unabashedly sexual, but my attention has always been drawn to the sheer awareness and sharpened senses of a young lover, when the beloved is near.

A favourite instance is Andre Aciman’s wonderfully evocative Call Me By Your Name. Narrated by 17-year-old Elio, harbouring a passionate love for an older man his parents host in their home, the book, almost operatic in its drama and intensity, pays homage to the physical form, as seen through a lover’s eyes:

‘… I longed to touch his knees and wrists when they glistened in the sun with that viscous sheen I’ve seen in so very few; that I loved how his white tennis shorts seemed perpetually stained by the color of clay, which, as the weeks wore on, became the color of his skin;…’

Aciman’s focus and gaze remains pointedly physical (though not exclusively sexual) throughout this story and the love is no less miraculous for it. This refusal to separate body and heart, the physical, the cerebral and the emotional, stands out sharply. This isn’t simply about finding a particular shape or body attractive, but about deliberately and deeply observing the hidden details that make up a person we cannot get enough of. Here, the body is a gateway, a messenger, a secret-keeper – a burgeoning world of discovery on the cusp of being loved into fulfilment. Here is where both reason and desire are nurtured and nourished, its every gesture an appeal, a rejection or acquiescence to what it loves. Aciman’s writing echoes Walt Whitman here when the latter said, ‘And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?’

(A scene from the movie ‘Call Me By Your Name’ ; Image via Indie Wire)

For The Love Of Drama

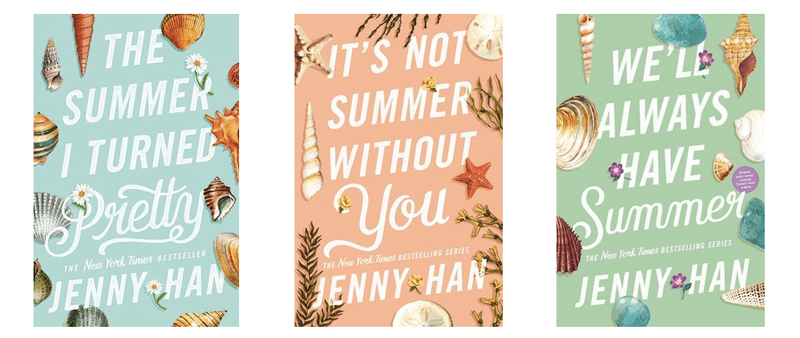

Though better known for that Holy Grail of teenage romances, To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, Jenny Han’s Summer trilogy made its way to me before its famous predecessor. The tale is simple, and old. Isabella, or Belly, as she is called, is caught between two brothers – Conrad and Jeremiah. The three books follow Belly from age 11 to her mid-20s in a delightfully soap-opera-ish tale of first love born in a special beach house over a series of summers. There is obvious hidden passion and emotional tugs-of-war as the trio dance around their friendship, their growing romances and the myriad misunderstandings that occur when love is everything but matured. It’s all wonderfully over-the-top, yet earnest as only a teenage love affair can be.

By the time I read it, my romance reading repertoire had an unconscious but strict common thread running through it – the quality of irony. In my 30s at this point, I did not see how one could look at love and not have a good laugh at its expense. Surely, a sly underlying sense of humour had to pervade romance for it to be sustainable. The Summer trilogy did not change my cranky old opinion entirely, but I adored the drama, the sheer importance attributed to love and the beloved and the never-ending overreactions that romance invariably brings – Why didn’t they text back, why didn’t they walk me home, why did they look at me, then immediately look away, what does that look mean?!

The best part is, this constant overthinking was perfectly justified, with no one telling the teens to be less intense or cause less drama. Because, while this constant overthinking is doubtless unhealthy in adult life, paying attention to love, calling it like it is without pretence or irony, seems to me to be fairly rational. And sometimes, if we need to show that we’re crazy about someone, or intensely, cripplingly hurt by them, the old ‘show and tell’ is far more effective than quietly breaking your heart.

As Belly says, ‘The first time I ever had my heart broken was at this house. I was twelve,’ I was reminded of the tenderness of that organ she speaks of, how much it holds and all that it hides as we grow older and acquire that much-vaunted adult quality of ‘chill’.

(Image via Mostly YA Lit)

And Then They Lived…

Some of these stories run their course to a fairly predictable ending, but many don’t. Many leave it open-ended because this is a ‘beginning’ kind of love that has a million possibilities ahead. Maybe they end up together and get married or maybe they simply hold onto one another over distance and difficulty. Maybe no one ended up together at all, but they never forgot another but never kept in touch either. In every one of these stories, though, there are immense learnings. Love is shelter, love is skin-on-skin, love is awkward, painful, and so big that it explodes your heart into fragments. Sometimes these fragments are like jagged, bloody eggshells, sometimes they’re stardust. Love is terribly inconvenient and entirely without irony and always, always showing up.

As I continue to grow as a lover, a beloved and a storyteller, I go back to many of these novels. The stories throw up new problems with every re-reading, but ultimately, they remind me that love is, in teenage words, a Very Big Deal. A deal that deserves big gestures and disgustingly mushy moments and possibly being obsessed with your beloved’s eyebrows.

How wonderful is it that, as adults with busy schedules into which we desperately try to pencil love in, we have such stories to remind us that there used to be another way. That there still is a world with tales of unending, loving courage waiting to draw us in.

Having worked in journalism and digital content, Tia writes and edits for a living, and reads to live. She believes in the power of storytelling, cupcakes and a good bottle of rosé.

Read her articles here.