Essay

adivaani: Documenting The Spirit Of The Adivasis

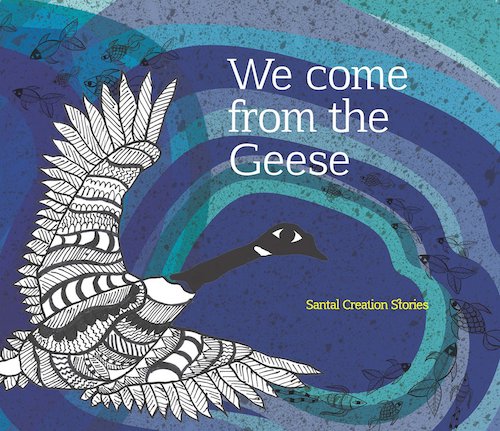

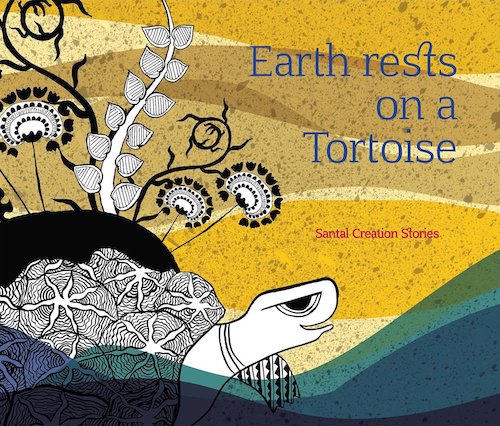

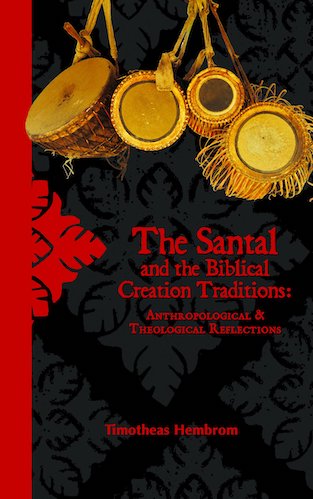

“In the beginning, there was no visible land, everything was under water. Thakur Jiv, the Supreme Being was present, as were the bongas–and many aquatic animals.” These are the opening lines of the Santal creation story—the genesis narrative of my people. Discovering these words in a book my theologian father wrote as his doctoral thesis, stumped me. Until then the only creation story I knew was of Adam and Eve. But I was also a descendant of the geese. I felt cheated of my identity by not knowing this account. How did the Biblical creation tradition become the only narrative for a Santal?

The realisation that this telling, retelling and sharing of our traditional stories were not common anymore, more so for families that took on a new religion or lived in cities or environments where the oral art form or storytelling was not a practice, filled me with a sense of loss; a mourning for a knowledge system I did not inhabit or inherit organically, in contact with my ancestral land and the millenial traditions of my people.

But I was not going to resign myself to this reality. I was going to cross over and engage with my culture, negotiate those spaces, inhabit those narratives and live the ideas, philosophies, histories, and expressions of my people.

My entry into publishing and cultural documenting was already a crossing over—born out of a threshold I had reached in my lived in experience of marginalisation and discrimination, when I realised yet again that Adivasis (indigenous peoples of India) were excluded from national discourses or public forums where ‘Indianness’ was discussed and projected.

My work became a project of representation and claiming space for our peoples but also a personal journey inwards, into questions of identity and belonging.

I was born to first generation migrant parents into the city. As a family, we struggled to adjust to the city ways; new languages, including English; the disbelief of having to pay for vegetables when you always grew your own food and then bearing the badge of being ‘backward’ and ‘uncivilised’ amongst those who couldn’t look at us beyond a cloud of prejudice.

I bore the stigma of indigenous/tribal stereotyping as a child, and spent many of my school years in Kolkata hiding and trying to be invisible. It was in school that I was ambushed with the reality of who I was or who I was seen as. I was defenceless and grew up with extremely low self-esteem. It was challenging to break through the external impressions of how others viewed me.

For the first 16 years of my life, notions of my being inadequate and inferior being drilled into me became my reality. And it wasn’t until another sixteen years more of that experience that I was able to push back, I was able to respond; I was able to take a stand. It wasn’t something I prepared for or planned or had an idea about.

It was something I strayed into.

In the April of 2012, I attended a 4-month publishing course, because I was between jobs and had the time. I wasn’t planning on making a career there. I was just investing four months of my time to learn a new skill.

The first month of the publishing course was called ‘Publishing Lives’—meeting the ‘who’s who’ of the publishing industry—national and international independent publishers, mainstream publishers, authors, poets, illustrators and printers. We met publishers who did exclusive writings of and for women, Dalits, etc. That they created spaces for specific narratives was inspiring.

When I paid attention to the list of people we were to meet, I realised that there was not one Adivasi name. It bothered me. Were we not important to be included as usual or were we non-existent? Non-existent we were not; despite a shorter writing tradition, we still write—we write in our native languages; but it wasn’t good enough to be part of this curriculum.

That did it for me–I wanted the Adivasi voice to be counted, someone had to do something–who would? Then I said, I would, without knowing how to and that was it. There it was: not a Eureka, Aha! moment but a tipping point – born out of the audacity to say ‘Enough is Enough’.

I said enough is enough to not being represented; I said enough is enough to others speaking for us; I said enough is enough to being labelled as unintelligent and non-thinking people, to being denied a place in history and literature, to the Adivasi narrative not being important enough to be documented, to the Adivasi voice being silenced and suppressed. That’s how adivaani, a platform for Adivasi expression came into being.

We had to find our own way to keep our work going. I had to improvise and customise.

Independent initiatives for an Adivasi like me grow out of human ingenuity and human struggle. It is that spirit that opened in me a floodgate and helped me find an outlet to channelise it for my people. I needed to choose as a medium of operation and dissemination a language that would give us universal reach and legitimacy and English was the pick. I knew that if we’d been writing and publishing in English, we’d more likely have a chance to be represented in the publishing course. I told myself, if that’s what it takes to be seen and heard, that’s what we’d do.

We had to be practical in choosing the legal status this enterprise would have. We decided on forming it as a public trust, a Non-Governmental Organisation—because we’d needed support to keep our operations in motion, not coming from wealth or having any seed fund to start with.

Resourcefulness keeps small operations like mine—in circulation. Brainstorming, customising, setting own rules, learning on the go, innovating and pushing and unleashing creativity are integral features of work like ours.

The stories of my community come first because they’re in danger of being lost. As a bearer and custodian of our traditional stories; it is my foremost responsibility to put them out on as priority and urgently.

We’ve never been in control of our own image, and expressing ourselves in and through multiform ways is a way of asserting our identity and controlling representation and imagery.

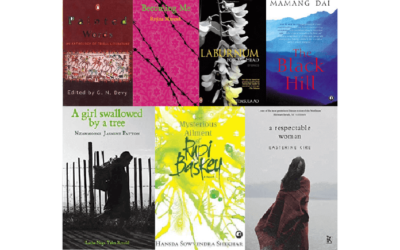

One of the larger challenges for adivaani has been fighting through stereotypes and prejudices that define Adivasi being. Our first book was in Roman Santali about the Santals as a people, their history and entity. The base of the cover for it is black. One of the printers we took the book to strongly recommended we change the black to a cheery yellow or maroon as “Black is too sophisticated a colour for the very backward Santals”. We stuck to black.

The distributors of an online book portal refused to take us on as “Adivasi books are not good”—that without even looking at our books.

Another concern is marketing and distribution. So what is our product? If entrepreneurship is business, what am I in the business of? We are in the business of indigenous information, knowledge, and culture—the tangible representation of which is a book, a CD, a piece of fabric, a sculpture, a painting. How do you market insight, experience, memory and traditions?

And it’s not costs we’re talking about here. Our books are very reasonably priced as the purpose of our books is defeated if our Adivasi population can’t afford them.

Making the connection of books, a video documentary or artworks, being a medium to preserve entire indigenous communities from extinction and cultural genocide is not an easy one. It is just looked at as a business, a business of culture perhaps. That though is just one way in which the magnitude of our aspirations is dismissed.

But you prod along, you hang on — only because being Adivasi (indigenous) is a responsibility – one you hold not only for yourself but for your community at large.

Being Adivasi also means a life of marginalisation, living in the peripheries, an existence in the blind spot and mind you being ‘formally educated’ does not make one immune from this discrimination.

But when we—first and second generation working professionals instead of consolidating individual careers put out our human ingenuity for the community, because we are equipped to, something empowering for the community emerges from that risk and investment of human potential.

Our work is about collective creativity. And understanding this dimension comes naturally to tribes. It is cultural that we think communally. It is in that mutual reciprocity that communities thrive, that’s how ideas and endeavours thrive.

Initiatives like adivaani aren’t a one time, solo, spark of genius—it is a continuous, collaborative journey of co-creating, problem solving and shared ownership. Adivaani wouldn’t be what it is without such collaborations and without a slice of everyone’s genius.

The only thing that will drive us now and challenge us constantly is how to remain relevant to our people. So you’re constantly pushing the limits to meet those challenges.

I am a descendant of a repressed people; living in repression. But I am not ashamed of my lineage of struggle. For me, living as an indigenous person is an intentional, purposeful deed—an act of resistance, resurgence and self-determination. My not doing that is disrespecting my ancestry, my being, and my identity.

These tools and products of documentation are the inheritance adivaani wants to leave behind for indigenous peoples and friends and supporters of indigenous people and every bit of help, acknowledgement gets us closer to doing that.

What we’re doing is nourishing a layer of life beneath our individual and collective efforts and contributions. We’re hoping our tipping points help tip the world just a little bit in our favour.

Ruby Hembrom is the founder and director of adivaani (first voices), a platform for indigenous expression started in July 2012 as a non-profit organization in Kolkata. Ruby is a Santal from Jharkhand, who's now made Kolkata her home. She is the writer of adivaani’s Santal Creation Stories for children, a recast of the Santal Creation myths in English and the prize-winning Disaibon Hul, on the Santal Rebellion of 1855–57. Her archiving, publishing and documentation initiative grew out of a need to claim Adivasi stake in historical and contemporary social, cultural and literary spaces and as peoples.

This is a wonderful, inspiring venture. Those of us growing up in mainstream cultures don’t realize the wealth of tribal traditions. Thank you so much, Ms. Ruby, for your vision in sharing these stories and your courage to put them out in the world! Well done!

Can your books be found in libraries in Mumbai ?

Hi Vishal. The books are available on Amazon and through the adivaani website.

Very essential service to the Adivasi community you are doing Ruby! We are a Panchgani based NGO and are trying to sustain and evolve indigenous arts in much the same spirit at Devrai Art Village.